Sometimes banks opt to consolidate in order to offer their clients access to bigger loans and better resources, while other times they unite as a competitive strategy against banks with more assets.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Community banks have many connotations associated with them. For the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the term refers to any financial institution whose assets are less than $10 billion, but for consumers it often refers to a financial institution who is accessible, in touch with the community, and has a vested interest in the success of its members.

In the famed holiday movie “It’s A Wonderful Life” big banks were depicted by the opportunistic, power hungry Mr. Potter who tried to acquire George Bailey’s wholesome community bank, which served the everyman. While an overly simplistic portrayal of the banking system, the movie does illustrate a reality small, community banks undergo: consolidations and mergers.

Sometimes banks opt to consolidate in order to offer their clients access to bigger loans and better resources, while other times they unite as a competitive strategy against banks with more assets. Regardless of the reason, the network of community banks throughout Central Massachusetts has transformed throughout the decades as smaller banks join forces with one another to create new entities.

“I do believe that in some cases when we look at the landscape and we don’t see the names that we saw when we were younger, sometimes when those banks team up it is done so that they can find those synergies to continue to help more people and I think the more people we help, the better off everyone is,” said Seth Pitts, CFO and executive vice president of Bay State Savings Bank in Worcester, which has $469 million in assets.

The economies of scale

Diversity of choice and competition are key in any market, and banking is no different. Larger, corporate banks and smaller, community banks all serve unique purposes, said Thomas Bartholomew, president of Worcester financial services firm Bartholomew & Co. Inc.

Banks make money based on the difference between how much they pay for deposits versus how much they can lend the money out at. In addition to lending, larger financial institutions have access to other means of revenue such as selling stocks, bonds, federal funds, preferred stock and matching fund loans and liabilities. Larger banks have more assets and therefore more lending power, however this also means they inherit more risks.

“That is what got us into these banking crises a couple of times, is that regulators could not evaluate what the risk really looked like,” Bartholomew said.

Local banks do not have the advantage of selling stocks, which presents the challenge of not having competitive funds compared to larger banks; however, they also forgo the dangers of larger risks, especially those associated with high stakes international loans.

Contrary to popular belief, consolidation is not always indicative a community bank is in decline, said Bartholomew. More often than not, it is because two institutions want to combine their assets and lending capabilities and cut costs as part of a competitive strategy.

Economies of scale are the biggest motivators for community bank consolidations as they try to decrease their overhead costs to remain competitive, he said.

Past banks like Flagship Bank and Trust Co. in Worcester, which merged with People’s United Financial Inc. of Connecticut, and First Massachusetts Bank in Worcester, which merged with TD Bank of Toronto, are just a few examples of once-known local banks consolidating.

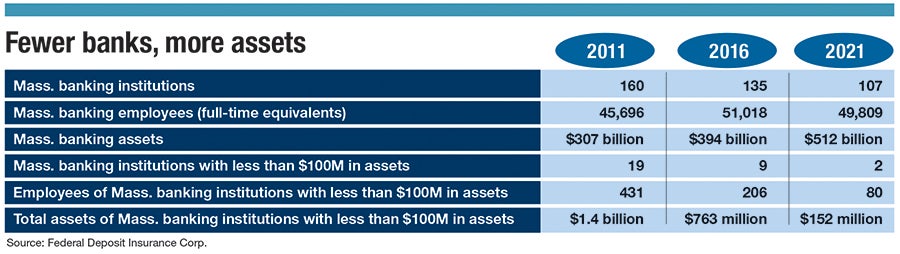

From 2011 to 2021, the total number of Massachusetts banks declined by 34%, even while the total dollar value of their assets increased 66%, according to FDIC.

Community banks’ most competitive advantage is their focus on service and relationship building, Bartholomew said.

“There is a want to do business with community banks because they can get things done quicker. You can tell your story to the president of the bank, maybe get someone to listen to you, versus a large community bank. Yet, they [bigger banks] are able to do larger transactions, so there is a place for both,” he said.

Cultural alignment

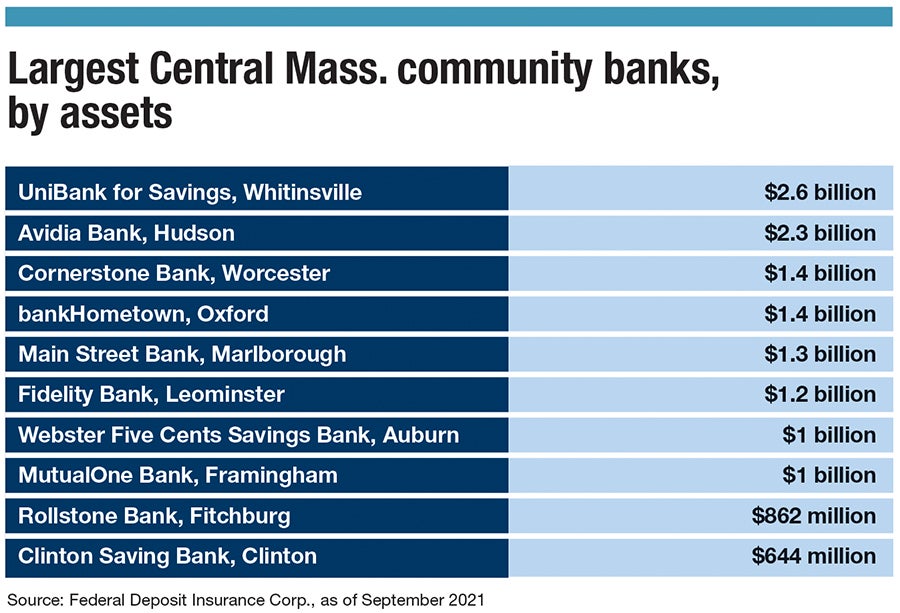

Regardless of asset size, all banks serve a unique function and are all a pivotal part of the American economy, said Ed Manzi, chairman and CEO of Fidelity Bank in Leominster, which has $1.2 billion in assets.

“Assuming all banks are the same is like saying all restaurants are the same because they sell food,” he said.

The world of community banking faces both cyclical challenges, such as the natural rise and fall of the economy, and secular changes, such as the technological transformation of financial services, Manzi said.

Staying current with the latest advancements is a costly necessity, especially for smaller banks.

“You have a lower market business while you’re growing and spending money to continue to meet the clients’ needs,” Manzi said.

Overhead capital is spent on hiring talented professionals for clients who prefer traditional teller services, while also investing in digital capabilities. In order to sustain escalating costs, community banks need to constantly grow in order to stimulate cash flow.

Fidelity Bank itself has completed three acquisitions over the past six years with Barre Savings Bank in 2016, Colonial Co-Operative Bank in 2018, and Family Federal Savings in 2020.

The leadership of each merged bank were thoughtful about the future and were culturally aligned with Fidelity Bank, said Manzi.

“The best way that they could think of, in the long term, to help the clients, communities, and colleagues that their bank cared about was to join a bank like ours that was bigger, to join forces with, and have the extra resources to continue to invest in its communities,” he said.

Selecting partnering banks who support the same mission is key to a sustainable acquisition. The merged banks were attracted to the bank’s values of helping clients reach their individual financial goals.

“We think it is a privilege to be a bank and to help people with their financial decisions and that privilege spills over trying to improve the quality of life in the communities that these folks live in,” Manzi said.

Pitts from Bay State, in echoing the personalized service offered by community banks, sees the entirety of the banking industry from a holistic perspective instead of one focused on competition, a place where banks run by Mr. Potter and George Bailey could co-exist.

“Harmony exists, and it is a good thing. You have a choice to make, we’d like it to be with us, but if not, that is okay too because we are all here, no matter what, whenever you need us, we will still be here with your support,” Pitts said.