When Framingham officials wanted to spur the redevelopment of a century-old brick mill building downtown, they offered a five-year tax break to a developer to kick-start what was planned as a $26-million project.

When global retailer TJX Cos. was looking to expand its headquarters, when Jack’s Abby Craft Lagers wanted to expand its brewery and when three developers were looking to build new apartments downtown, Framingham officials reached tax break agreements again.

Framingham has been among the most proactive Central Massachusetts communities when it comes to using tax-increment financing agreements, or TIFs, to entice existing companies to stay and expand or to draw others from outside the city.

Its next-door neighbor, Natick, offers a stark contrast.

While Framingham has signed nine tax breaks in the past two decades, Natick has agreed to just one: with MathWorks when the software company was building a planned $150-million campus starting in 2009.

“We don’t see the need to compete with other communities in offering TIFs,” said Melissa Malone, the Natick town administrator. “We are in a unique and fortunate position where businesses are naturally looking for general space between our boundaries.”

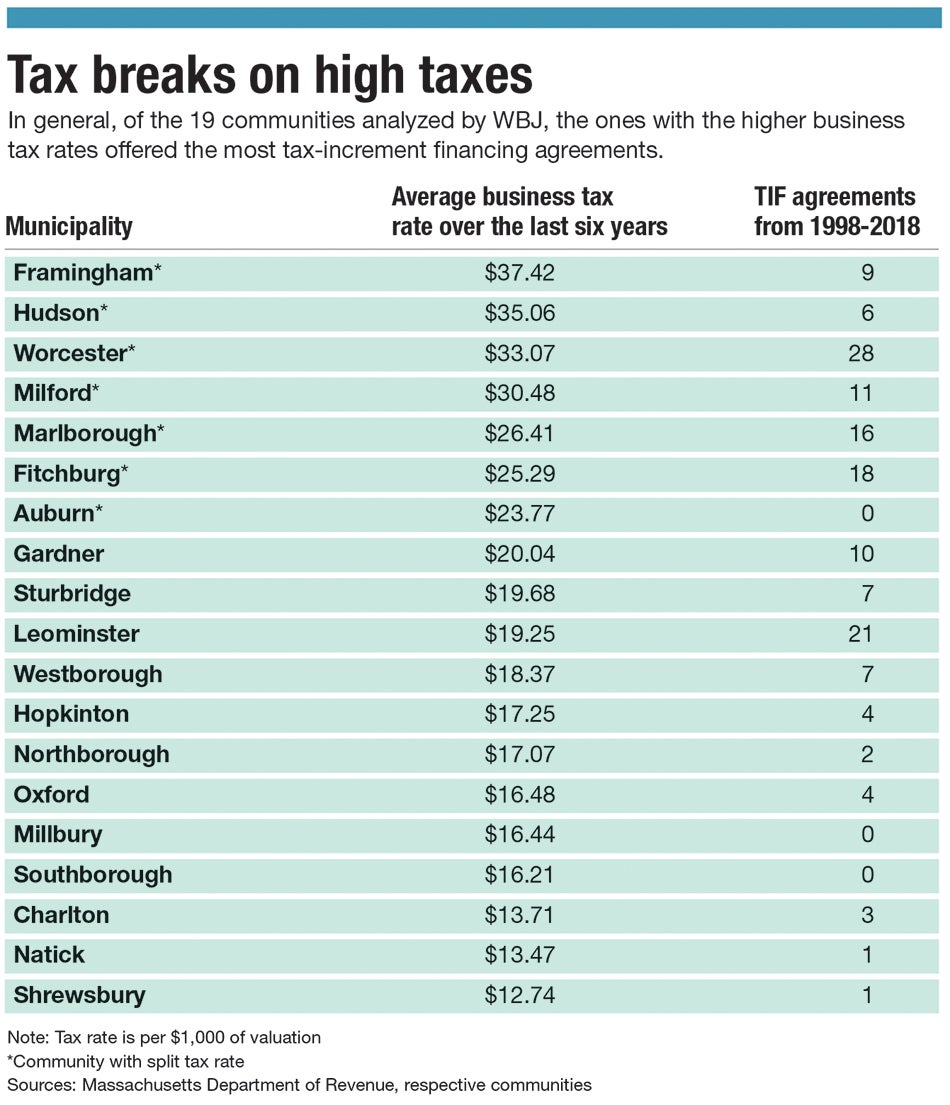

A Worcester Business Journal examination of 148 tax breaks given by 19 of the largest Central Massachusetts communities in the past 20 years shows local governments have varying philosophies with how tax breaks should be used as an economic development tool. Worcester has signed 28 such agreements, Leominster has made 21 and Fitchburg has made 18.

While the region’s largest communities might be expected to most often reach tax-break agreements, another correlation shows. Tax breaks have been more common in communities where commercial and industrial tax rates are highest, demonstrating cities and towns might be choosing the success of some companies over offering the lowest tax rates for all businesses.

The tax rate in Framingham, for example, is close to three times as high as Natick’s. Worcester has the region’s highest such rates in 2019, at $34.90 per $1,000 in valuation, followed closely behind by Hudson and Framingham. Fitchburg and Milford also have split tax rates, where commercial and industrial property owners pay a higher rate than residential homeowners.

“It’s a valuable tool,” Thomas Moses, the Hudson executive assistant, said of tax breaks, of which the town has had six in the past 20 years. The town prioritizes job creation when looking to offer companies incentives, he said.

“We’re very concerned with employment for Hudson residents, and if a big company is taking a look at Hudson, we have been very active and interested in providing a TIF,” Moses said. “We use it as leverage to make sure jobs stay here in Hudson.”

Other communities haven’t used tax breaks at all, including Auburn. That’s not due to any philosophy against them, Auburn Town Manager Julie Jacobson said, but simply because there haven’t been any companies that have asked who were good fits for the town.

“We do not get a lot of requests from companies,” Jacobson said. “We are absolutely supportive of [tax breaks] for companies that are qualified and that will produce a tangible benefit to the town.”

Proactive cities

While communities like Natick and Auburn have rarely or never used tax breaks, others have been heavily active, like Fitchburg, Leominster and Marlborough.

Fitchburg is focused on building a broader commercial tax base, said Tom Skwierawski, Fitchburg’s executive director of planning and commercial development. That means the city helps with tax breaks for both manufacturers to keep jobs in the city and places like Great Wolf Lodge to bring hotel tax revenue and visitors.

Fitchburg has issued tax breaks to keep blue-collar jobs in the city, including its 2000 deal with Caraustar Industries, in which the Georgia packaging company received a 20-year tax break in return for a $100-million investment to its paper mill. The city has gone in the other direction, too, giving a tax break in 2009 for a Marriott Courtyard – and again just five years later when the same property was turned into Great Wolf Lodge.

“That could have been anywhere else,” Skwierawski said of Great Wolf Lodge, part of a national chain of hotel-and-waterpark developments. “But it came to Fitchburg.”

Gardner, in an area reliant on manufacturing, has only so many choices to support its manufacturers and help them stay and grow, said Mark Hawke, Gardner’s mayor since 2008. TIFs can be virtually the only option.

“The municipal toolbox is small and shallow,” said Mark Hawke, the Gardner mayor. “It really just includes a TIF. There’s very little else in our toolbox.

“If we can do a little something to help them make their finances work better, we do it all the time,” Hawke said.

Marlborough has signed TIF agreements with corporate giants including the pharmaceutical company Sunovion, TJX, and medical technology companies Boston Scientific and Hologic.

That’s in large part due to fierce competition between communities to land such corporate tenants, Marlborough Mayor Arthur Vigeant said. The mayor compared communities chasing the same companies to how Target and Walmart compete for the same customers.

Leominster has averaged about one tax break a year for the past two decades, nearly all going to manufacturers. Dean Mazzarella, the city’s mayor for the last 25 years, said Leominster has helped manufacturers when the local industry was struggling.

“Many of those companies are still here,” Mazzarella said.

Recipients include Fosta-Tek Optics, Easy Pak and Process Cooling Systems. Process Cooling began building a new facility in December with more than 60,000 square feet in the Southgate Business Park.

While Sturbridge isn’t exactly as active as those cities, it does have a very detailed TIF policy passed in 2017 spelling out what the town looks for. Prioritized are companies bringing tourists into town. Companies already seeking building permits for an expansion are out, because they’ve demonstrated they were ready to build even without a tax break.

“We’re cautious of how we use it because it’s such a powerful tool,” said Kevin Filchak, Sturbridge’s economic development and tourism coordinator. “We’re making an investment in this by saying we’ll reduce the tax break for you. We want to make sure the investment is going to benefit our local economy.”

The big-company advantage

In the 148 TIF agreements reviewed by WBJ, tax breaks have represented both major investments by large companies and small expansions by family-run businesses.

Boston Scientific said it would spend $250 million expanding its office campus in Marlborough when it signed a tax deal in 2006. Hanover Insurance Group said it would spend $194 million on an expansion in Worcester, and although it fell short of that, it did spend $135 million.

But companies don’t always have to promise much to get a tax discount.

In total, 19 companies got tax breaks while pledging to spend less than $1 million, and 31 got tax breaks while committing to add fewer than 10 jobs — or no particular number of jobs at all.

Smaller firms who might promise less in a tax break are often less likely to receive a discount on their taxes in the first place, said David Merriman of the University of Illinois Chicago, who studies tax policy. Larger companies are the ones with the ability to pay good negotiators or lawyers, or the wherewithal to seek TIFs in the first place.

“The smaller companies are the ones who can’t negotiate,” he said.

In fact, with so many companies might not knowing where to look, Lynn Tokarczyk has been providing help for companies looking to secure tax breaks for the past 15 years. Her company, Business Development Strategies Inc. of Medway, has worked recently with furniture maker AIS, laser manufacturer IPG Photonics and equipment provider Primetals Technologies to help land agreements.

AIS got a tax break in 2013 in Leominster in return for a $13-million investment to move into a vacant 537,000 square-foot building on Tucker Drive. In the past year, IPG got a tax break to expand in Oxford, and Primetals moved from Worcester to Sutton to build a $28-million facility.

“These programs help keep Massachusetts competitive,” Tokarczyk said. “The tax incentives are beneficial when companies are in process of making their corporate real estate decisions. It has to be the right kind of company and partnership, because it’s required to be voted upon by the municipality and state.”

The tax-break recession

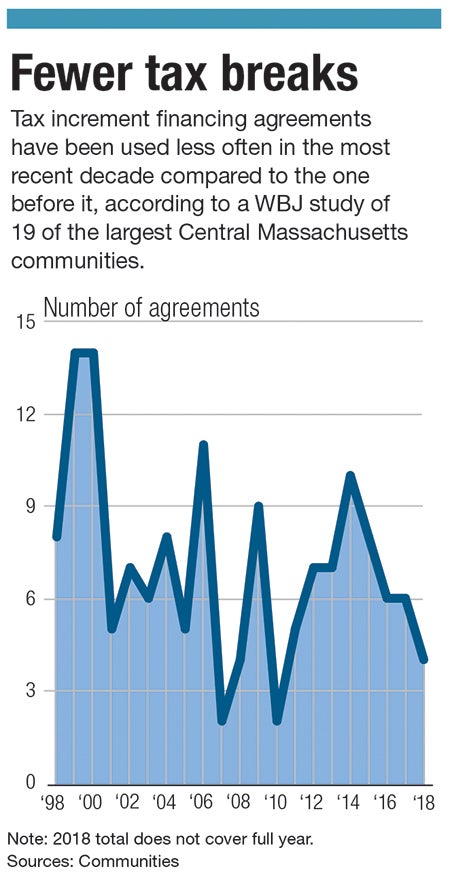

WBJ’s review found tax breaks are signed less often than two decades ago. The use of TIFs hit a peak before the Sept. 11 attacks and the Great Recession that followed, with eight deals signed in 1998 and another 14 in 1999. Two were signed in 2007 and four in 2008.

In the two-decade span analyzed by the WBJ, the first decade – 1998 to 2007 – included 80 tax breaks. In the following decade, there were 64.

Local governments often deal with ballooning pension and other employee retirement costs, as well as keeping up with other needs at a time when state aid doesn’t always keep up with costs.

Skwierawski, of Fitchburg, wasn’t surprised that TIFs have gotten slightly less common in recent years.

“With all the financial liabilities we have, you do have to be a bit more discerning in the projects you do approve,” Skwierawski said, “and why it’s more important for a project to be part of a larger vision and not just about getting a project done.

“I’m sure it’s no coincidence that it peaked before the recession,” he said.