Public companies across the country – as well as others in Central Massachusetts including TJX Cos. and Hologic – have been spending more money than ever buying their own shares.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

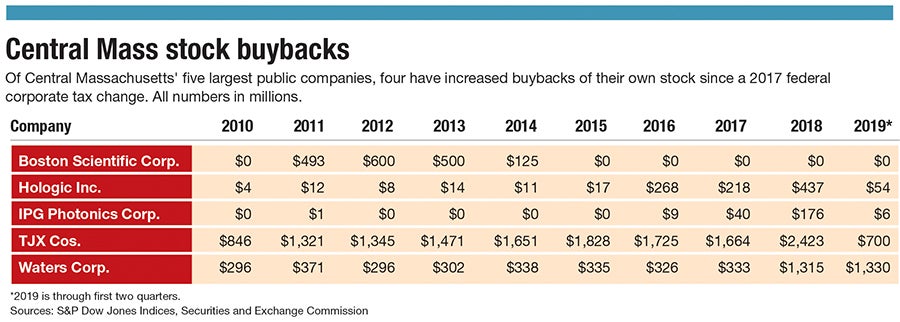

In the first half of 2019, Waters Corp., a Milford scientific equipment maker, bought back more than $1.3 billion worth of its own stock: as much as it did from 2014 to 2017 combined.

Since a 2017 federal corporate tax change, Waters hasn’t been alone.

Public companies across the country – as well as others in Central Massachusetts including TJX Cos. and Hologic – have been spending more money than ever buying their own shares, a process dividing economic experts on whether the trend has been a good or bad one.

To supporters, stock buybacks – in which a company purchases its own shares off the stock market – are another way of using money to make investments, and a sign of a company’s self-confidence.

To detractors, the record-setting buybacks are a sign of a failed trickle-down benefit from the 2017 federal tax cut and a way for a company’s shareholders – including its own top executives – to get richer at the expense of the company’s everyday workers.

Among the strongest critics is William Lazonick, the president of the Academic-Industry Research Network in Cambridge. Lazonick has advocated for banning buybacks, arguing they enrich shareholders at the expense of workers or broader investment at a company.

“That’s what’s gone by the board here,” Lazonick said of a benefit to everyday workers.

Benefit to investors

Joseph Foley, an accounting professor at Assumption College in Worcester and the founding dean of its new Grenon School of Business, said he sees virtually no trickle-down gain to workers at such large public companies. Supporters of the federal tax overhaul said corporate savings would be passed on to workers and consumers.

“It certainly doesn’t trickle down in the big companies,” Foley said, expressing more confidence smaller firms without the same shareholder pressures have used savings more for investment or worker benefits.

“I’d like to see at least a recognition that they do have a social responsibility,” he added of the larger companies.

Others support buybacks, including Steve Ng, a finance professor Clark University in Worcester, who said public companies exist to maximize value for their shareholders. Companies want to be a good corporate citizen but most put those thoughts aside for the good of those who have their money in that firm, he said.

“I want to invest in a company that will look out for me, because I’m making the investment,” Ng said.

Buybacks can simply shift – not replace – investment, Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at New York University told investment firm Goldman Sachs in an interview. Some companies are buying back stock that shouldn’t be and workers aren’t sharing in as much of the windfall as they could be, he said, but more broadly, buybacks allow money to be invested in companies providing better opportunities.

Less debatable is another effect of buybacks: They support a company’s stock price by having fewer shares on the market, and make earnings-per-share look higher for the same reason

Almost one in four companies on the S&P 500 Index boosted their earnings-per-share last year by reducing their share count in such a way, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices.

A U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission study found companies benefited from a 2.5% stock-price boost on average in the 30 days after announcing a buyback.

“It does support the stock, whether it’s a good investment or bad,” said Howard Silverblatt, a senior industry analyst at S&P Dow Jones Indices, a firm closely tracking buybacks.

Yet even SEC Commissioner Robert Jackson is a critic. Jackson, who was appointed by President Donald Trump in January 2018, criticized companies in a speech five months later for using tax savings on what he called massive buybacks instead of on retraining their workforce or raising wages. At a Center for American Progress conference in Washington last June, Jackson advocated for regulatory changes including limiting the ability for executives to cash out using buybacks.

A national spike

Despite those debates, buybacks have soared since federal tax reform was approved late in 2017, lowering tax burdens for corporations from 35% to 21% and freeing up money for a range of uses – including buybacks.

Beyond that, companies had another incentive to spend: what the Tax Policy Center calls the liberation of $3 billion in overseas profits.

Before the tax overhaul, many of the largest American companies left profits overseas to avoid taxes. But with the new tax plan allowing companies to use that money for buybacks or dividends for the first time, the Tax Policy Center said, companies are now doing so.

Buybacks jumped by 55% in 2018 compared to the prior year, hitting $811 billion, according to Goldman Sachs. Goldman projected in April for buybacks to rise even further this year to $940 billion.

Companies may have bought back so much stock they’re now pulling back fairly significantly, Silverblatt said – not to pre-2017 levels but less than last year.

After each quarter in 2018 set a record for total buyback costs, first-quarter buybacks this year fell by nearly 8%, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. With nearly all second-quarter buybacks reported, that number is expected to fall by another 18%, down to around $167 billion.

Silverblatt doesn’t expect a significant further drop but more like a new normal of around $170 billion a quarter,.

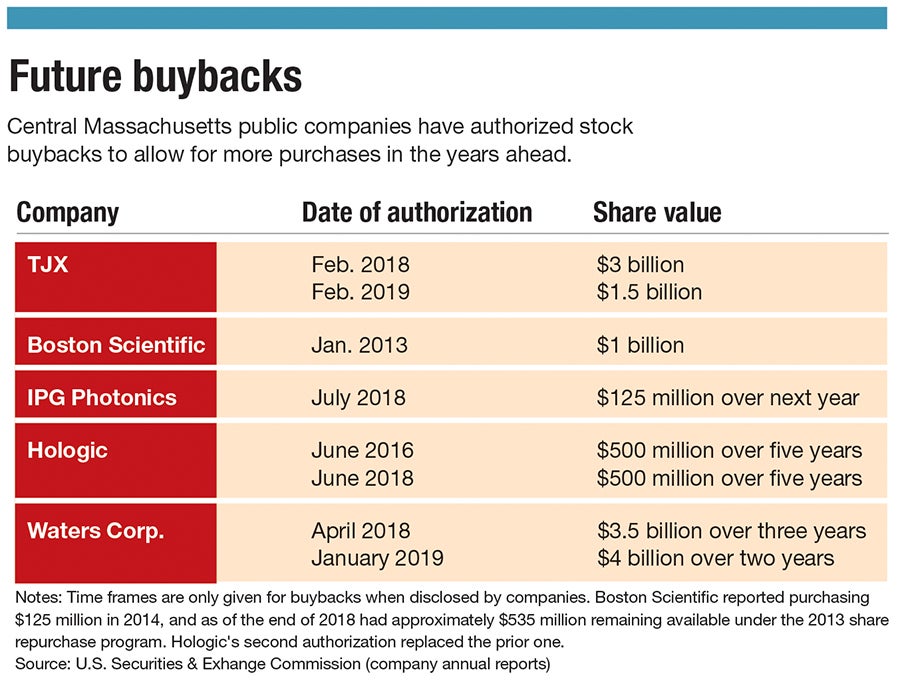

The largest public companies in Central Massachusetts have already authorized more repurchases in the years ahead. In January, Waters approved $4 billion over a two-year stretch.

“As long as you see cash on corporate balance sheets,” Ng said, “they will buy back shares.”

Billions spent in Central Mass.

Buybacks among the largest public companies in Central Massachusetts have soared since 2017.

Waters spent $1.3 billion on buybacks last year, with the company making clear in its annual report the benefit of doing so: a 34-cent-per-share earnings boost. Waters said it bought back stock to return capital to shareholders while staying flexible to redirect investment elsewhere.

Waters has also directed money elsewhere, spokesman Jeff Tarmy said, including research and development, whose budget has jumped 40% in five years, and in acquisitions, which include $30-million for an Indiana firm's mass spectometry technology last year.

Framingham retailer TJX Cos. – which has spent more than $3 billion on buybacks in the year and a half since federal tax reform – has portrayed its program similarly to Waters, saying in its annual report its earnings-per-share would have been adversely affected if it didn’t purchase shares. It has also raised dividends, with 2019 marking its 23rd straight year with such increases.

The retailer said in a statement its strong financial returns and cash generation have allowed it an ability to both return cash to shareholders and invest in the growth of the business. The company is planning more than $1.1 billion in capital investment this year.

Oxford laser manufacturer IPG said in a statement its $216 million in repurchases since 2017 have been done as part of an anti-dilutive program following the issuing of shares for compensation to employees and directors. Higher spending on buybacks in 2018 allowed the company to fully offset the so-called dilution effect of issuing stock to employees and directors, IPG said.

Marlborough medical device manufacturer Hologic said its $491 million of buybacks since 2017 were made to cover employee tax withholding obligations under its equity incentive plans.

There’s one notable exception to the buyback spike locally: Boston Scientific. The Marlborough medical device maker hasn’t reported any buybacks since 2014, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Instead, Boston Scientific has been on a buying spree.

The company’s acquisitions this year alone include a $4.2-billion purchase of BTG, a British cancer and vascular disease device firm, and $465-million for Vertiflex, a California biotech making a device to treat patients with lumbar spinal stenosis.