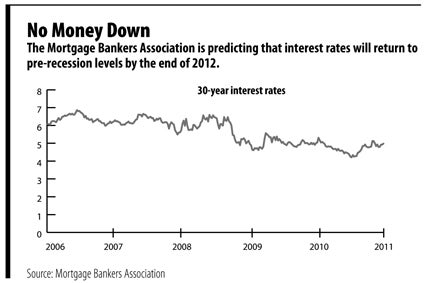

For potential homeowners, now seems to be a pretty good time to take out a long-term, low-rate fixed loan. Interest rates on 30-year loans around the country are hovering at or below 5 percent, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association in Washington, D.C.

But those long-term fixed-rate loans can present challenges for financial institutions.

Many banks essentially finance long-term loans using deposits from customers. When the rates for deposits rise, as they are expected to, banks don’t want to have too many long-term mortgages with fixed low rates on their books because they could cut into the bank’s margins.

So, while it’s a good time for homeowners, it can be a challenging time for bankers.

“When, not if, interest rates go up, which we have no control over, all of a sudden depositors will be demanding higher rates,” said Gordon Edmonds, president of Leominster Credit Union.

Banks don’t want to be stuck with a bunch of 5 percent mortgages that they can’t touch, he said.

It creates somewhat of a paradox, said Michael Fratantoni, vice president for research with the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA).

“It’s really the homeowner’s advantage right now,” he said. “If rates go up, they’re protected by a fixed rate. If they go down, they can refinance at lower rates.”

There are, however, solutions.

Banks want to keep lending to well-qualified borrowers, according to Richard Bennett, president of Marlborough Savings Bank. So one way to manage long-term, low-rate mortgages is for banks to repackage and bundle loans, then sell them on a secondary market run by, for example, Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, which are companies that buy, sell and trade bundled mortgages as securities.

These markets allow the bank to make loans to consumers while hedging some of the risk associated with the low-interest rates.

Even that, though, can present challenges.

In the wake of the financial meltdown, secondary market underwriting standards have become much stricter. That’s a good thing, Bennett said, but in some cases it may also require banks to change their underwriting standards to comply with the secondary markets.

Local banks know their borrowers and Bennett said they are willing to work with members of the community to get loans done. But when loans are bundled together, banks have to make loans to underwriting standards that are acceptable on the secondary markets.

Bennett said Marlborough Savings Bank underwriting standards haven’t drastically changed, but some banks may have to make bigger changes than others to meet the secondary market standards.

Another way banks could manage low rates is by having adjustable rate mortgages, or ARMs, which allow banks to raise rates to market levels.

But the term has become a toxic buzzword associated with the financial collapse, according to Jed Smith, a research director at the National Association of Realtors in Washington, D.C. It’s too bad, he said.

“The problem in the crisis was not adjustable-rate mortgages,” he said. “It was that there were too many poorly-written adjustable-rate mortgages.”

Other bankers say there are more pressing issues than managing long-term fixed interest rates. The biggest one: Demand.

“If you asked me what the greatest challenge is, I would say it’s that demand is low,” said Paul Gilbody, executive vice president of Bay State Savings Bank in Worcester. “People and businesses just aren’t borrowing money like they use to.”

Gilbody said the market is better than it was a year or two ago, but it’s still deflated compared to historical levels. What will fix it? Macro-economic trends, he said.

“It’s just part of the cycle and the recovery from 2008,” he said.