When Central Massachusetts companies look to fill software, programming or research jobs, they’re increasingly looking to foreign labor under an immigrant work program called H-1B.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When Central Massachusetts companies look to fill software, programming or research jobs, they’re increasingly looking to foreign labor under an immigrant work program called H-1B.

The number of such foreign workers in the area ballooned by 37% in the past five years on record, and nearly sixfold in the past decade, according to federal data.

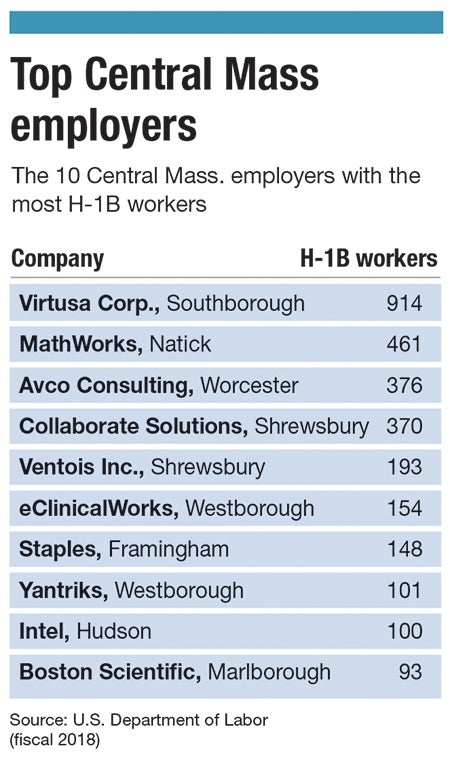

That influx of workers has helped companies like the Natick software firm MathWorks, the Southborough information technology services company Virtusa and Worcester’s Avco Consulting, which works with IT and pharmaceutical firms.

Such visa workers, however, aren’t getting approval from the federal government like they used to, potentially imperiling the growth of companies saying they aren’t able to find enough qualified American-born workers for these jobs. And even when H-1B applications are approved, the government is taking longer to review cases and asking for more documentation than in the past, according to those who work with businesses on the forms.

“This is really hurting businesses, and especially in Massachusetts,” said Eva Millona, the executive director of the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition, a Boston advocacy group known as MIRA.

Millona and others who closely follow H-1B visas say the program has been purposefully hampered by the President Donald Trump Administration, which wants to ensure Americans have the first crack at jobs over immigrants. Critics of the program like the Washington D.C. think tank Economic Policy Institute argue major H-1B employers use the program for cheaper labor for outsourcing work.

But those in the industry say companies turn to such workers because they can’t find enough qualified American-born workers, like those with training in STEM subjects.

“What’s the driver here?” said Scott FitzGerald, a partner at the Boston offices of the immigration law firm Fragomen, arguing the Trump Administration is simply looking to limit immigrants in the workforce. “It’s pretty clear the drive here is [pandering to Trump’s political] base.”

Without enough native-born workers, businesses go through what’s described as an arduous process of applying to the government for approval, with applications sometimes as thick as four inches, packed with identifying forms and sponsorship letters, said Kirk Carter, the chair of the immigration practice group at the Worcester law firm Fletcher Tilton.

When Carter’s career started 25 years ago, a three-person team at Fletcher Tilton would handle such immigration employment cases. Now, it’s five lawyers and eight or nine support staff.

That’s a measure of both how much demand has increased from employers and, more recently, how much the government is demanding for documentation. Back then, Carter said, maybe 1% of applications were met with demands for further information, known as RFEs. Today, it’s more like 70%, he said.

“We used to call it tax season,” Carter said, comparing his team’s rush before the annual April 1 deadline for H-1B applications to the annual tax filing deadline two weeks later.

“Now,” he added, “we call it RFE season.”

A major economic impact

With the state’s high-tech industry, H-1B workers fill a disproportionate number of jobs in Massachusetts, landing the state seventh nationally.

On a per-capita basis, the Massachusetts lands third behind New Jersey and California in H-1B visas, and its total more than doubles the five other New England states combined, illustrating the state’s standing in the tech industry.

A decade ago, 99.5% of H-1B applications in Massachusetts were approved, making the process nearly a sure thing. That rate, still much higher than national rates, fell to 97.2% in 2013 and 99.2% in 2018.

A decade ago, Central Massachusetts companies relied on these visas far less than today: MathWorks employed just 33 H-1B workers, or 1 for every 13 it has today. Virtusa and eClinicalWorks, two other major employers, had similar ratios. Avco Consulting in Worcester used just eight, compared to 376 a decade later.

UMass Medical School in Worcester has consistently turned to H-1B workers for research assistants, database and software engineers and similar jobs. The school is the 13th largest employers of such workers in Central Massachusetts.

Jobs that UMass fills with H-1B workers are highly skilled, with a limited pool of American-born workers to fill them, said Vanessa Paulman, UMass’ director of immigration services.

“For post-docs,” Paulman said of researchers who have their doctorate degrees, “there’s just not a whole lot of U.S. students that are pursuing PhD’s in the sciences.”

H-1B workers, while a small share of the area’s total workforce, tend to work in high-paying jobs.

The average pay of an H-1B worker in fiscal 2018 in Central Massachusetts was $86,861, according to what companies posted with the U.S. Department of Labor when they applied for approval for those positions. At major employers of such workers, including Bose Corp. and MathWorks, average pay exceeds $98,000.

The largest H-1B employers in Central Massachusetts largely didn’t want to talk about their involvement, declining or ignoring requests for comment.

MathWorks declined to comment for this story, but in 2017, Co-founder and President Jack Little told Boston radio station WBUR the company has long had a hard time finding qualified workers.

“There’s always been a shortage in the full history of the company’s existence. It’s always been hard to find talented programmers,” he said to WBUR.

Nationally, the crunch is so severe the government stopped accepting applications this year just four days after the April 1 opening for submissions because the capacity had been reached.

Around two-thirds of these workers are on computer-related occupations, according to a 2018 U.S. Department of Homeland Security report. Nearly all the remainder are in fields including architecture, engineering, education, medicine and health.

Two-thirds of H-1B workers are between the ages of 25 and 34, according to the Department of Homeland Security. Roughly three out of four are from India, another 9% from China, and the rest scattered among Canada, South Korea and other countries.

Nine out of 10 had either a bachelor’s or master’s degree. The remainder had a doctorate or professional degree.

A resource in danger

Congress established the H-1B program in 1990, setting an initial ceiling of 65,000 new visas each year, a limit raised temporarily to as much as 195,000. It dropped back down to 65,000 in 2004.

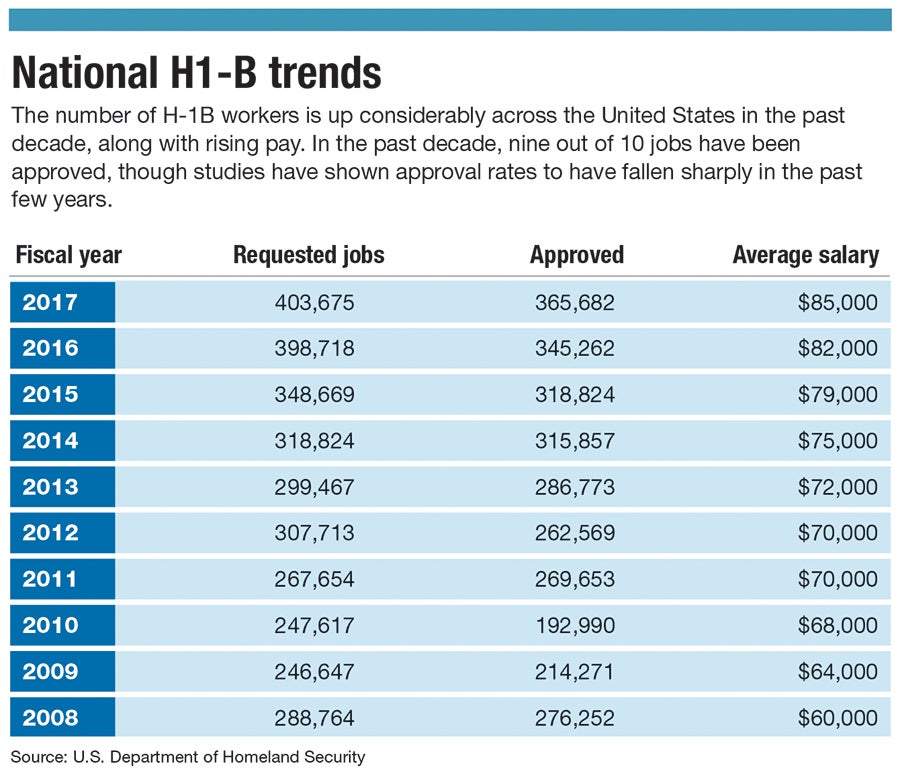

Employers apply for H-1B visas for a three-year period, with an extension for up to another three years. For years, employers were very likely to get federal government approval for H-1B workers – at least a nine-out-of-10 chance.

That changed with the Trump Administration.

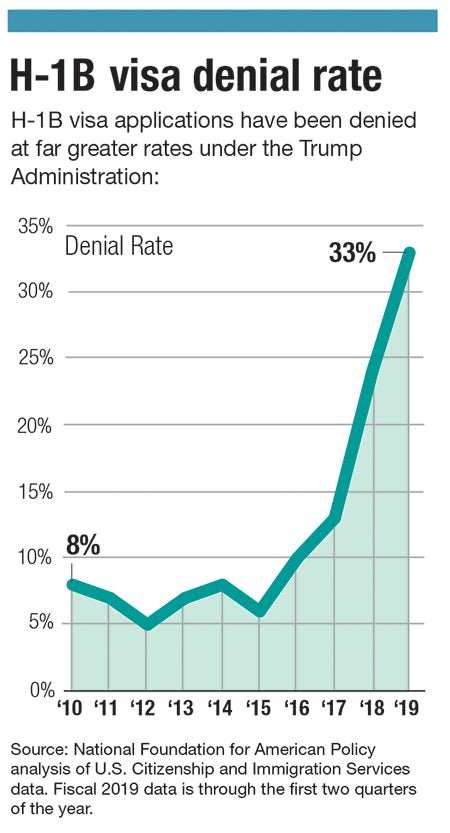

From fiscal 2015 through halfway through fiscal 2019, the denial rate rose more than fivefold. Exactly one out of three applications was rejected through the first half of this fiscal year, according to an analysis of federal data by the National Foundation for American Policy.

Another trend making it harder to employ H-1B workers – an increase in requests for evidence – has now hit 60% nationally, the group said. The most common reason? Employers didn’t give sufficient evidence for why the job was specialized.

Employers may be finding the program is becoming too much trouble. In 2017, the number of applications submitted to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which oversees the H-1B program fell 16%, its first decline in five years, according to the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

“If the goal of the Trump Administration is to make it much more difficult for well-educated foreign nationals to work in America in technical fields, then USCIS is accomplishing that goal,” the National Foundation for American Policy said.

UMass Medical School, which employs 169 H-1B workers today, has such a high demand for those workers it pays a higher fee for Citizenship and Immigration Services, Paulman said.

“The government is definitely cracking down a lot on H-1Bs,” she said. “There’s a belief that there’s enough U.S. workers to fill those jobs. It’s our job to prove that the job is specialized and that we need a visa worker. They highly scrutinize every position.”

Employers have become concerned about the high denial rates, said Sifat Ahmed, who practices immigration law at Fletcher Tilton. And those employers need H-1B workers, she said, with a reported rate of American citizens or permanent residents making up only one out of five computer science and electrical engineering graduates.

“Companies based here in New England experience this deficit in their recruitment and are compelled to recruit international graduates,” said Ahmed, who grew up in Saudi Arabia. “For the growth of these burgeoning industries, which support the U.S. economy, it is necessary to fulfill any deficit in recruitment by turning to international STEM graduates.”