As the President Donald Trump Administration is pushing for profound cuts to both National Institutes of Health and Medicaid funding, Central Massachusetts community leaders, business owners, and patients are sounding alarm bells over the calamitous effects they say will spread to everyone.

On Thursday, 15 advocates, business leaders, and treatment recipients gathered at UMass Chan Medical School in Worcester to speak with Congressman Jim McGovern (D-MA) at a roundtable to discuss the implications of the Trump Administration’s ongoing attempt to cap indirect costs for new and existing NIH grants to 15% with House Republicans proposing capping federal spending on Medicaid, which would sever up to $2.3 trillion over the next 10 years.

Guangping Gao, UMass Chan professor and director of the school’s Horae Gene Therapy Center, foresees the potential cap on NIH funding meaning the patients he treats with neurodegenerative diseases won’t be able to access the same level developing treatments they need. Gao’s lab focuses on rare diseases, mainly those that are neurodegenerative, in addition to respiratory, liver, and muscle diseases.

“We (won’t) have further growth. We’re not going to have future new hires of the talents to expand our research. And, more importantly, we cannot translate whatever we have in laboratory space to patient use,” Gao told WBJ.

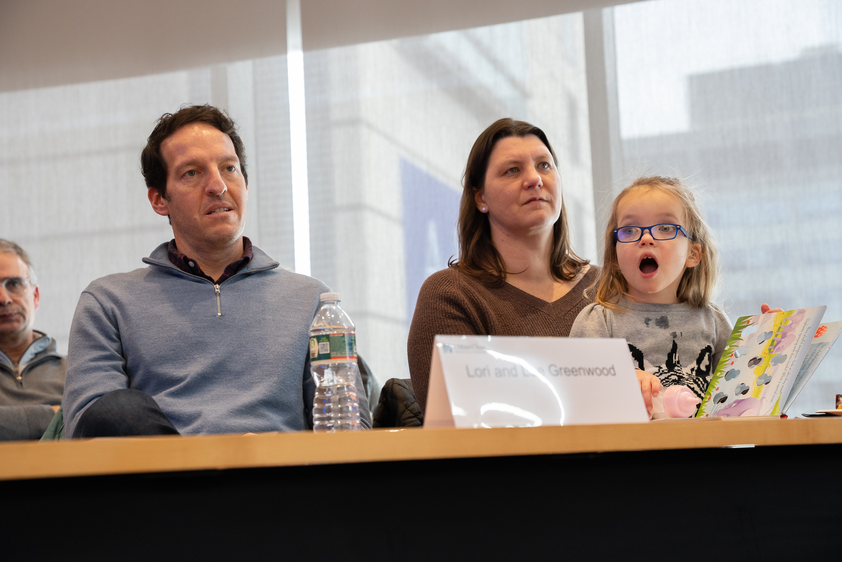

Gao’s gene therapy treatment significantly altered the life of Noa Greenwood, whose parents spoke at Thursday’s roundtable. Noa has Canavan disease, a rare and progressive genetic neurodegenerative disorder impacting the nervous system with a life expectancy around 10 years. She began gene therapy treatment developed by Gao in June 2022 which has allowed her to live a life her prognosis would have deemed impossible.

“None of this is possible,” said Lee Greenwood, Noa’s father. “She would likely be on a feeding tube. She would certainly not be sitting here, reading her playful penguins book. She wouldn’t be speaking. She wouldn’t be in Boston Public School. None of that would have existed but for intervention of the clinical trial and that gene therapy was developed right here.”

The 15% cap would cut UMass Chan’s NIH funding by $50 million, said Dr. Terence Flotte, UMass Chan provost and executive deputy chancellor. While a subset of those funds are used to keep and maintain a safe environment to perform research, the majority of the financing goes directly to support the university’s buildings, paying off debt, utilities, and operating costs.

And while some may argue that research can be picked back up again in four years once Trump is out of office, that is simply not the case, said Joel Richter, professor of molecular medicine at UMass Chan.

“Aside from just experiments you can’t have interrupted, it’s getting people into the labs to do the sort of work,” he said.

Creating novel therapeutic advances is highly specialized work and those who are able to do it are not in abundance, he said. The country is already experiencing a paucity of people pursuing postdoctoral research with Richter seeing a stark decrease in postdocs coming to the U.S. from regions like Europe and Asia. Once that pipeline is turned off, it won’t restart, he said.

Erik Sontheimer, professor at the RNA Therapeutics Institute at UMass Chan, said the NIH cuts would make themselves known at multiple levels. While he sees the largest impact being the severing of the future conduit of researchers, immediate effects on employment will be seen on the national level and in Central Massachusetts.

“A lot of folks think that when there are cuts to the federal budget, when there are cuts to NIH these are cuts that occur in DC, they don’t realize that these are cuts that occur down the street. These are cuts that occur here in Worcester,” said Jon Weaver, CEO of business incubator Massachusetts Biomedical Initiatives in Worcester.

The region has experienced 84% growth in biomanufacturing jobs in the past five years as Central Massachusetts is becoming a global leader in bringing products to patients, Weaver said. The NIH cuts would both sever the vital pipeline of drugs reaching patients and leave potentially thousands in the area without jobs.

Weaver said it’s critical “that we recognize that some of the even small changes, as far as the timing of awards and as far as the indirect rates and all these different little details within this have a direct impact on jobs here locally, have a direct impact on the companies that might fail as a result, and the potential patients that won’t get impacted by those cures.”

Those research and employment consequences would directly impact Shane Byrne, co-founder of biotech startup Codomax located at MBI. Codomax is solely funded by NIH small business grants with no outside investors. If no new grants are funded, Byrne may have to close his company.

“If we shut down, it’s going to be really hard to start up and get to do this work again and really enable others, including ourselves, to make products that can really impact patients,” said Byrne. “Biotechs are surviving on these small business grants because the investment economy is not great. It’s hard for companies to even get off the ground right now without some of these government funded grants.”

Organizations offering direct healthcare to patients will experience employment cuts and loss of patient access to care with the proposed Medicaid cuts just as severe as with the NIH caps.

“If Medicaid went away, let alone cut, if it went away even half, it would mean striking massive amounts of care. We either close one of our big sites or pair down our care entirely, or it will wither away entirely. We basically become a private practice and unable to serve people most in need,” Steve Kerrigan, president CEO of the Edward M. Kennedy Community Health Center in Worcester.

Last year, Kennedy Community Health Center, which is the 10th largest human services nonprofit in Central Massachusetts, served 34,878 patients across Central Massachusetts with 91% of those patients at or below the double poverty level and 74% receiving care in a language other than English.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say it would be cataclysmic if [Medicaid funding] went away,” said Kerrigan.

Seven Hills Foundation, Central Massachusetts’ largest human services nonprofit, will see thousands of patients lose access to care throughout Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire, said Bill Stock, vice president of government and community relations for Seven Hills.

The organization supports 60,000 patients on an annual basis while employing 5,000 with an annual budget of half a billion dollars.

“Medicaid dollars run through everything,” said Stock.

For example, 93% of those receiving care from the organization’s behavioral health counseling are on MassHealth (the state’s Medicaid program) and all the residents of Seven Hills’ 300 residential group homes are on Medicaid.

“To be honest with you, it’s quite frightening to hear the conversations that are coming out of Washington, DC, to know the impact that those cuts will have to our programs and to the people that we support is terrifying,” Stock said.

The region’s smaller human services providers will risk closure with Medicaid cuts, like Community Health Awareness Network Grows Equity in Worcester.

CHANGE supports low-income African immigrants in the region and state, including helping them apply for MassHealth benefits.

“We help people who will normally fall through cracks,” said Lovo Koliego, nurse, president, and founder of CHANGE.

Not only will the Medicaid cuts mean CHANGE will have to cut down individual employee hours, it may have to shutter completely.

When people are not as able to access primary care, treatable conditions will send them into critical condition, said Dr. Stephanie Carreiro, emergency medicine physician and medical toxicologist at UMass Chan.

“When we take away resources to care for people, a lot of people are going to become more sick and even die from completely preventable things like diabetes and hypertension,” she said.

But these funding restrictions won’t just affect those with active medical needs, they will harm everyone’s ability to receive care, said Carreiro.

More patients will show up to emergency rooms, further clogging departments already pushed to capacity.

Central Massachusetts received a massive blow to its hospital and emergency room bed shortage when Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer closed in August. Dr. Eric Dickson, president and CEO of UMass Memorial Health in Worcester said surrounding hospitals do not have the room or workforce to accommodate the consequential influx in need.

With looming cuts to Medicaid funding, the potential patient outcomes will be sobering.

“Everyone will suffer because now there’s not enough space to secure everyone else,” said Carreiro.

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.