It wasn’t long ago CEOs were notably absent from such societal debates. For decades, business heads were advised not to talk about hot-button issues such as religion or politics.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Dr. Eric Dickson runs the largest employer in Central Massachusetts, and as the president and CEO of UMass Memorial Health Care in Worcester, Dickson has seen the hospital system through the coronavirus pandemic and at one point treating a few hundred affected patients at a time.

What was one of Dickson’s most passionate addresses this year to employees was not pandemic-related though. It was about the killing of George Floyd and the following national race and equality movement.

Dickson sent a 1,200-word email the same June 5 afternoon when he stood with a few hundred doctors and other health providers for a rally called White Coats for Black Lives. The gathering of employees at UMass Memorial and UMass Medical School on the Worcester campus they share included 10 minutes of silence, slightly longer than the length of time a Minneapolis police officer kneeled on Floyd’s neck, killing him.

“In my mind,” Dickson said in the staff email, “racism is a deadly, life-altering disease just like cancer, heart disease or COVID-19. Is there a cure for systemic racism? We clearly haven’t found one yet.”

In a phone interview, Dickson, who is white, said he didn’t hesitate to be outspoken on the issue.

“For those of us in medicine, we think of this like a disease, like a cancer,” he said. “What happened to George Floyd is like a symptom of the disease.”

It wasn’t long ago CEOs were notably absent from such societal debates.

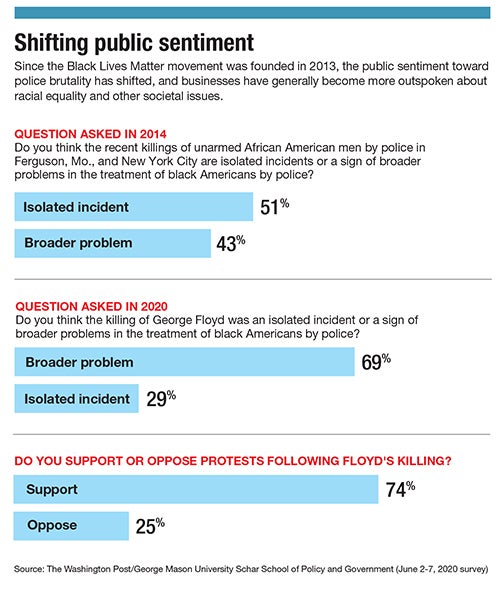

For decades, business heads were advised not to talk about hot-button issues such as religion or politics, said Peter Cohan, a strategy lecturer at Babson College in Wellesley. That mindset held even through the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black man, in Ferguson, Mo. Before the Floyd case, Brown’s death was perhaps the biggest flashpoint in modern race relations.

“A lot of companies didn’t say much” then, Cohan said. “Over time, there’s been a growing feeling that more and more CEOs need to speak out on political issues.”

A changing attitude

Leaders of major businesses have spoken out far more in the past few years than they would have before.

Dick’s Sporting Goods CEO Edward Stack ordered a ban on selling assault rifles after the Parkland, Fla., school shooting in 2018. A range of companies cut ties with the trade and lobbying group National Rifle Association after the Florida school shooting.

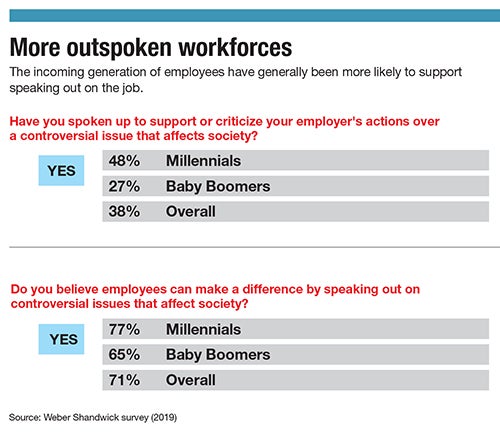

CEOs are becoming more outspoken because their employees – especially younger ones – want them to, said Nicole Melton, a professor in the Isenberg School of Management at UMass Amherst.

“Silence is deafening,” Melton said. “When you’re silent, you’re complicit.”

A national 2019 poll by the New York public relations firm Weber Shandwick found 48% of Millennial workers considered themselves employee activists; they spoke up to support or criticize their employer’s actions over a controversial issue affecting society; 38% of all workers felt the same way, including 27% of Baby Boomers.

Polling now shows most Americans to be in support of racial equality efforts, giving business leaders less reason to hesitate to be outspoken.

In a Washington Post poll released in early June, 69% of American adults called the killing of black Americans by police to be part of broader problems. When the question was asked in 2014 following Brown’s death, 43% felt that way.

Taking a stance on a divisive issue appeared to pay off for Nike. The stock price of the company rose 5% and its value increased $6 billion in the year after it began an advertising and merchandising campaign with former professional football player Colin Kaepernick, who stirred controversy by kneeling during the national anthem in protest of racial inequality.

Central Mass. leaders speak out

Luis Pedraja, the president of Quinsigamond Community College in Worcester, was among the first prominent business leaders to speak out after Floyd’s death. He and QCC’s police chief, Kevin Ritacco, each issued a statement to the college community.

Pedraja, who was born in Cuba, wrote colleges value differences, protect dissent and engage in civil discourse. Ritacco said he was “appalled, disgusted and disillusioned” by Floyd’s death.

In a phone interview, Pedraja said he wasn’t sure what to say after the incident but knew he couldn’t be silent. QCC’s student body is 14% black and 21% Hispanic, and nearly half of its students are people of color.

“I felt compelled to say something because it was such an emotionally jarring event, to see somebody murdered in that way,” he said.

Other Central Mass. business leaders followed suit.

Chris O’Connell, the white CEO of Milford laboratory equipment manufacturer Waters Corp., said in a statement he was outraged by Floyd’s killing. New efforts at Waters, he said, include appointing a senior diversity and inclusion officer, mandatory training on the issue, and open-office hours in which executives will talk to employees about inclusion.

At Marlborough medical device maker Boston Scientific Corp., Chairman and CEO Mike Mahoney, who is white, said the company’s leadership team would expand employee conversations about the issue and urged workers to speak up if they experience or witness intolerance or bias.

Ernie Herrman, the white president and CEO of TJX Cos. in Framingham, said the retailer’s diverse employee base makes it stronger, but it’s striving to do better. TJX said 57% of its workers are people of color, and 34% of managers.

Jack Roche, the white president and CEO of the Hanover Insurance Group in Worcester, said the company would listen and learn.

BJ’s Wholesale Club, the Westborough retailer, issued an unsigned statement in early June on Twitter calling Floyd’s death senseless and heartbreaking and attesting the company is “against racism and discrimination in all forms.”

It isn’t clear how much local businesses are contributing in tangible ways to racial equality efforts, unlike other causes. Local businesses have touted donations made to coronavirus-related causes this year, and many are highlighting June as Pride Month by using rainbow images in their social media, including Hanover and Waters. Announcements of donations or Black Lives Matter imagery have not followed in nearly the same number, although the Worcester Railers Hockey Club announced $10,000 in donations to causes fighting for racial equality.

Guidance for business leaders

Two black college business professors, writing in the Harvard Business Review, said businesses have to take meaningful action against racism. The writers, Laura Morgan Roberts at the University of Virginia and Ella Washington at Georgetown University, urged businesses to acknowledge harm black coworkers have endured, to affirm workers’ rights to safety, and think critically about how they can use their power to bring change.

“Employees value words of understanding and encouragement,” they wrote in HBR, “but leaders’ and organizations’ actions have a more lasting impact.”

Roberts and Washington advised against potential missteps, including staying silent and overgeneralizing about others’ experiences.

Melton urged leaders to amplify black voices in their organizations to be an effective ally.

Others cited potential inconsistencies between a company’s statements and the daily experiences of its employees, or whether statements ring hollow based on its actions.

“There’s an element of fakery about some of these statements that I think people will dismiss,” Cohan said.

Dickson, who as the head of UMass Memorial made headlines last year for backing a proposal to expand Medicare to all, had a few words of advice for leaders worried about saying the wrong thing.

“Listening is always safe,” he said.