Diversity, equity, and inclusion leaders have some of the highest turnover rates among executives. The cause is manifold, but it often has to do with the organization a CDO is serving.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

In the two years since Leigh Woodruff became chair of the City of Worcester’s diversity and inclusion advisory committee, which is meant to advise the city manager on equity issues, she has never seen City Manager Edward Augustus attend a meeting.

“The city manager … has never attended one of our meetings or communicated directly with me as the chair over the last couple years,” Woodruff said. “It’s only an advisory committee, and the person it’s supposed to be advising has not communicated with the committee or taken the committee’s advice.”

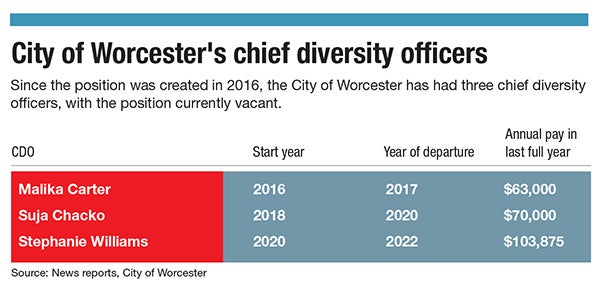

The disconnect between top leadership and those working for diversity in Worcester was laid bare when Stephanie Williams, the city’s chief diversity officer, became the third CDO to leave the position since it was created in 2016.

In her letter of resignation, Williams’ wrote there is a “culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion being an extracurricular activity without embracing all that a properly experienced CDO can do. Chief diversity officers need more than a title to succeed.”

In response to Woodruff’s claims, city spokesperson Robert Burgess said Augustus was following protocol. “It has never been the practice of city managers to attend the city’s board and commission meetings,” Burgess said in a statement. “In this case, the CDO is the liaison between the committee and the city administration. The city manager has adhered to that protocol while having many conversations with the CDO about the committee’s work.”

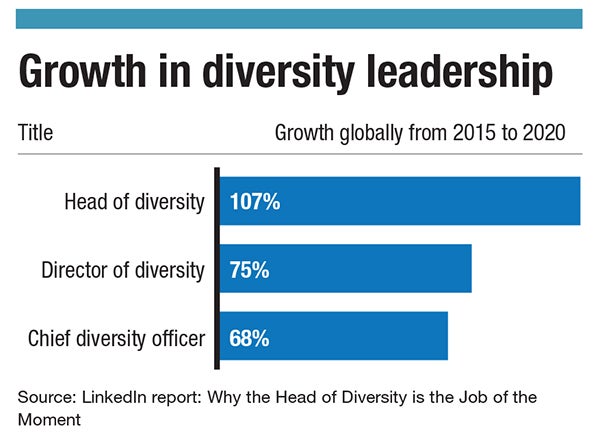

In Central Massachusetts, an increasing number of healthcare, education, and governmental institutions have added the diversity officer title – or some variation of it – to their staffs in the last five years.

From 2015 to 2020, the number of people globally with a “head of diversity” title grew 107%, according to a report from social media platform LinkedIn. In the two years since Minneapolis police murdered George Floyd, hiring of new diversity chiefs within Standard & Poor’s 500 index nearly tripled, according to global management consulting firm Russell Reynolds Associates.

At the same time, diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) leaders have some of the highest turnover rates among executives, according to a report from the Wall Street Journal. The average turnover for a diversity executive is three years, as opposed to more than five years on average for other c-suite positions, such as CEO, chief operating officer, and chief financial officer.

The cause of these turnover rates is manifold, but it often has to do with the organization a CDO is serving.

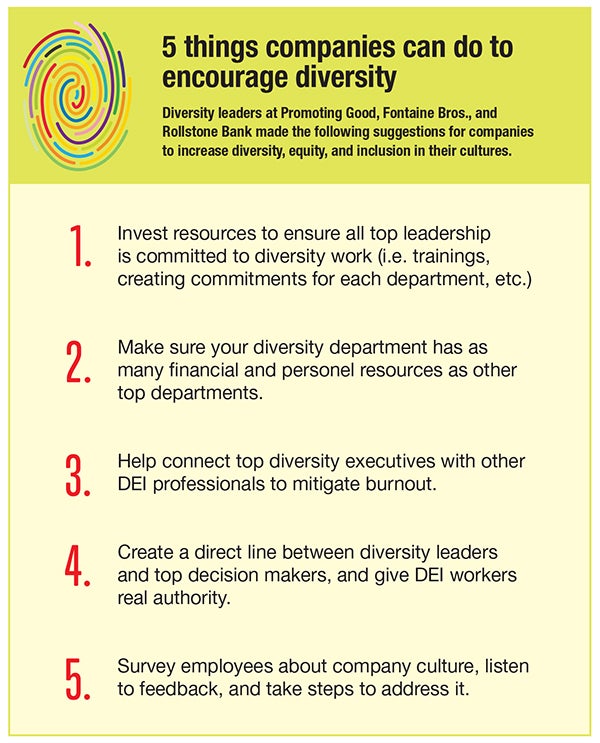

“In the wake of the uprisings that happened nationally, I think organizations felt like they had to do something, and so they did the thing that everyone else was doing,” said Valerie Zolezzi-Wyndham, CEO of diversity consulting agency Promoting Good, LLC in Upton. “But, I don’t think that organizational leadership … really understood what would be required so that a person in that role could succeed.”

The role of a CDO is by no means simple, as they are striving to build an equitable workplace environment, whether it be by trainings, hiring practices, or surveying employees. At its heart, the goal of a DEI leader is to essentially address and dismantle structural inequities that have existed for decades, if not centuries.

More and more companies are recognizing the importance of investing in this work, both for ethical reasons and profit-based ones. Improving workforce diversity and cultures of inclusion leads to better customer orientation, employee satisfaction, and long-term decision making, ultimately growing profit margins, multiple studies from global consulting group McKinsey & Co. show. Firms with DEI employees are 22% more likely to be seen as an industry leader with high-caliber talent, according to LinkedIn data.

Though arduous, diversity work is possible, Zolezzi-Wyndham stressed, but it is up to organizations to genuinely engage in making it successful.

Support structures for success

For Liz Wambui, who was hired in 2021 as director of diversity, inclusion, and community at the Fontaine Bros. construction firm in Worcester, support from other diversity professionals has been paramount in her success.

“It’s invaluable,” she said of her relationship with the diversity professional at Fontaine’s partnering contracting company, Dimeo Construction in Providence, R.I. “Just having someone who you can call and just ask the silliest or the most serious question, helping me think through how to deal with certain situations, and offering up resources.”

Wambui is Fontaine Bros.’ first-ever diversity officer and has a leadership background at the Nativity School in Worcester, so her colleague at Dimeo has helped guide her through the worlds of both contracting and diversity.

At companies like Fontaine Bros., the position has existed for only a handful of years, so there aren’t many structures in place or other professionals who have previously served in the position.

“The biggest challenge in starting work at a newly created role is just that: You're starting from scratch,” said Amy Bonilla, the first-ever chief diversity officer at Rollstone Bank & Trust in Fitchburg.

Personnel support is not only necessary for advancing equity, but it helps mitigate turnover, as DEI work can be incredibly taxing with often incremental progress, said Bonilla.

“Cultural change is a marathon, not a sprint,” she said. “It's a long, never-ending process. I can imagine that a lack of support and resources could lead to job frustration.”

Rollstone Bank created the CDO role in December. Bonilla is not on her own, however; she oversees a newly formed diversity, equity, and inclusion committee made up of representatives from each of the bank’s divisions.

In the case of Rollstone, the CDO is embedded in human resources, which differs from Fontaine Bros., where Wambui reports directly to Vice President Dave Fontaine, who leads most ventures at the company.

“One of the things that I think I’m very lucky to do is to be reporting directly to Dave Fontaine. You have to be able to be in direct communication with the decision makers in order for the decisions to be made,” Wambui said.

Increasingly in the business world, CDOs are a part of the c-suite executive team. Yet, many still face barriers to gaining authority and direct access to top leadership, ultimately stunting diversity progress within an organization, said Zolezzi-Wyndham.

“People who take these jobs are super passionate and knowledgeable and really want to see change happen,” she said. “Then they have suggestions for how those issues can be addressed and then the system – whether it’s leadership or others – push back because often it’s really hard to hear.”

“We’re on board, you fix it”

As evidenced by Worcester’s situation, however, diversity work can come to a grinding halt when DEI professionals are not sufficiently and genuinely reinforced by top leadership. Since Williams’ resignation, the diversity and inclusion advisory committee has ceased all operations.

“We felt like we’re just giving this false impression by even having these meetings that work is being done. The work is not being done,” Woodruff said, adding the committee has spent over a year on a memo with recommendations on hiring practices for police and fire departments, which has garnered zero response from the city leadership.

In cases like the City’s, a single CDO may not be able to make progress because they don’t have the resources, support, or authority. After a couple years, a smart, passionate leader will look elsewhere for work.

“As white people in powerful leadership positions … we look at people of color and say, ‘We’re on board, you fix it,’” said Woodruff. “This puts all of the responsibility for change on the people that historically have not had the power, and on one person or one small group of people, usually people of color, often women, that are in these positions.”

While addressing systemic inequality is a profound challenge, the high turnover rate among diversity leaders seems to be more reflective of the organization than of the job itself. If a company wants to hire and retain a CDO, it must take a hard look at its existing leadership team and culture.

“The answer isn’t that this work is impossible. There are lots of organizations where we have seen real change,” said Zolezzi-Wyndham. “There are organizations where leadership at a top level is really serious about the work.”

Diversity leaders should not be the sole bearers of DEI work, but rather a guide and partner for top leadership, as every decision maker has their own individual commitment to equity, she said.

“For organizations that are not sort of at that maturity level, the real work that those leadership teams should be committing resources to is to their own professional development and coaching to get to a place where they could support the strategy,” she said. “The solution is to start again, try to do a better job of understanding your needs, and be open to change.”