In Framingham, the influx of Brazilians has been particularly crucial to the revival of a former mill town going through hard times.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When Enzo de Sá’s father moved from Brazil to Massachusetts in the late 1980s, it was no surprise he ended up in Somerville, which was then the center of the state’s Brazilian immigrant population. He opened AMAZONia Insurance, largely serving that community. But when Sá took over the business a couple of years ago, he realized the company needed to add a new office – in Framingham.

“Drive through central Framingham, it’s like every single shop has a Brazilian flag,” Sá said.

Sá, who serves as the company’s vice president, said the Brazilian community in Framingham grew out of families leaving Somerville when rents got too high. Meanwhile, new waves of immigrants from Brazil have joined long-time residents, and continue to do so today.

Overall, Massachusetts is one of the biggest destinations in the U.S. for people from Brazil. And Brazilians are among the most-represented immigrant groups throughout communities in Central Massachusetts.

“Obviously, the Brazilian community is a big part of our diverse population here in the city of Worcester,” said Alex Guardiola, director of government affairs and public policy at the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce. “We need to be able to kind of encourage them to make their mark here and continue our economic growth.”

He said one distinct mark Brazilians have made on Worcester is in the culinary field, with restaurants and bakeries.

“It’s just an asset to the city as we are a big foodie city, and it adds to the quality of food we have here,” Guardiola said.

Taken advantage of

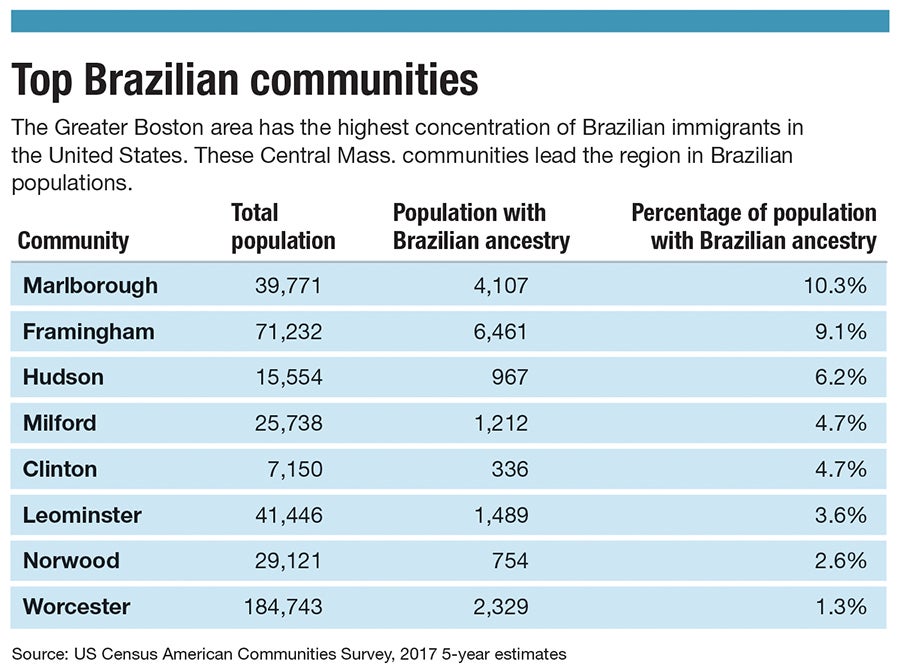

Along with Florida, Mass. is the top destination for Brazilian immigrants in the U.S., according to Census data, and the Greater Boston metro area has the highest concentration of Brazilian immigrants anywhere in the country.

In Framingham, the influx of Brazilians has been particularly crucial to the revival of a former mill town going through hard times.

“It was really cheap, so the Brazilian community moved in, and they just made everything beautiful again,” Sá said. “Things are growing really rapidly, and everything’s getting nicer.”

Like many immigrant groups, Brazilians are more likely than native-born U.S. citizens to run small businesses. In Massachusetts, 18% of Brazilian-born workers are self-employed, compared with 6% of the general population, according to 2017 Census data. Sá said many immigrants ran their own companies in Brazil and have skills translating to self-employment. But also, he said, it’s partly about the way some workers have been treated poorly by employers.

“They get taken advantage of, not paid,” he said.

That’s a particular problem for people who don’t have legal status, who may fear going to authorities if they get ripped off. And Sá said another serious problem is in Massachusetts, unlike in 14 other states including Connecticut and Vermont, undocumented people aren’t allowed to get driver’s licenses.

“They can’t get to work, they can’t get to school,” Sá said. “They get forced into terrible situations where they essentially have to drive without a license.”

Sá said his company’s clients are largely businesses owned by Brazilian immigrants, like general contractors. Many offer work to newly arrived people from Brazil. Sá said one of his roles is supporting immigrants as they learn about how insurance, business laws, and other Massachusetts systems.

“We teach them,” he said. “Otherwise these guys get taken advantage of really hard.”

In general, Brazilian-born Massachusetts residents earn considerably less than their native-born peers, according to the Census. Median full-time annual earnings for men from Brazil were $47,000 in 2017, compared with $66,000 for the state’s male general population. The difference for women: $30,000 for those from Brazil, compared with $55,000 for all state residents.

Raquel Riberti-Bill, program director at ProGente Connections in Framingham and Marlborough, said one reason is U.S. employers may not accept the professional qualifications immigrants bring with them from Brazil.

“We see a lot of Brazilians who hold teaching credentials in Brazil, and they’re here working as a cleaner,” Riberti-Bill said. “We want to make sure they have the same chances as everybody else in this country.”

Teaching Brazilians about U.S. business

ProGente, a nonprofit working with local churches, offers educational programming to bridge the gap between Brazilian immigrants and others in MetroWest. It initially offered classes in Portuguese as a heritage language to help new generations of kids keep their families’ language. Now, it provides English classes for the general public.

In addition, Riberti-Bill said, the organization is now adding new programming designed to help immigrants in their professional and personal lives. One new offering is teacher certification coaching, aimed at helping those teachers with degrees and experience from Brazil get licensed in Massachusetts.

For young adults, ProGente is planning a different coaching program to help them apply to colleges and seek financial aid. While the public schools offer that kind of help for young students, Riberti-Bill said, immigrants who are past high school age may need help figuring out how to get a degree that could advance their careers.

“What happens with the young adults in their 20s, 30s who were raised in different country, when they come over here they have no idea how to apply to college,” she said.

In addition to those two targeted coaching programs, ProGente is planning two public workshops. One is a general introduction to U.S. laws and customs for immigrants, and the other is about doing business in Massachusetts.

“The idea is just to teach them if they want to open their own business, what are the laws and regulations in this country that they need to be aware of?” Riberti-Bill said.

Riberti-Bill said her interest in these kinds of programs stems from her experience after moving to the U.S. from Brazil in 2013. She was a Portuguese teacher herself, but she didn’t initially find a way to teach in the U.S. So she was thrilled to get connected with an organization that helped her find a one-day-a-week teaching job on top of other work she was doing.

“It was one of the ways that I found myself, through finding this organization, to say ‘OK, I want to pursue my career,’” she said. “For me, it meant a lot to be working in my field.”