In 2016, the College of the Holy Cross gained $83 million in investment income in its endowment. That’s about 16 times greater than the entire endowments of Anna Maria College or Becker College.

Such is often the financial reality in higher education today, with those three Central Massachusetts colleges demonstrating how wealthier institutions benefit from hefty finance accounts and generous donors, while smaller schools face what some in the industry warn may be insurmountable challenges in the years ahead.

“It illustrates a perverse dichotomy in higher education that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer,” said Scott Latham, a business professor at UMass Lowell, who has been studying endowments and the higher education industry.

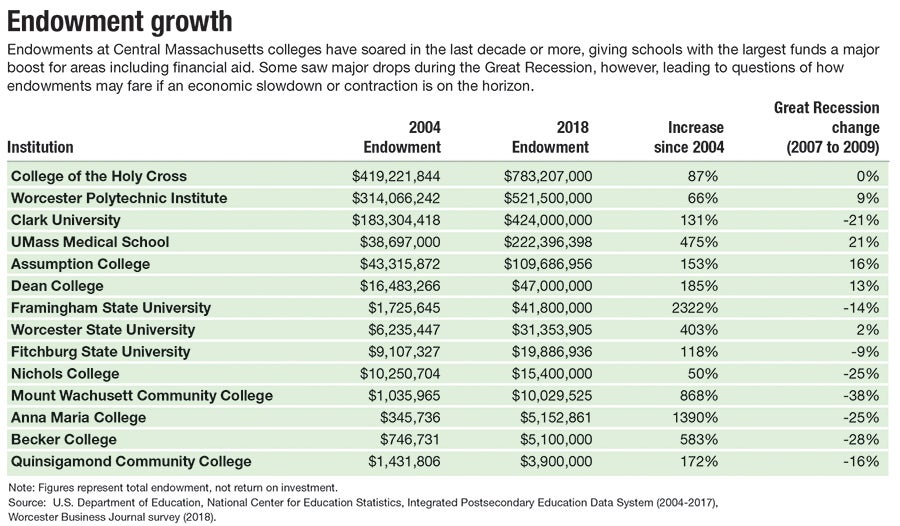

Colleges with smaller endowments may be getting relatively poorer compared to deep-pocketed peers, but with the economy providing higher investment returns – and more donor support – nearly every Central Massachusetts college has seen endowments grow in the past decade or more.

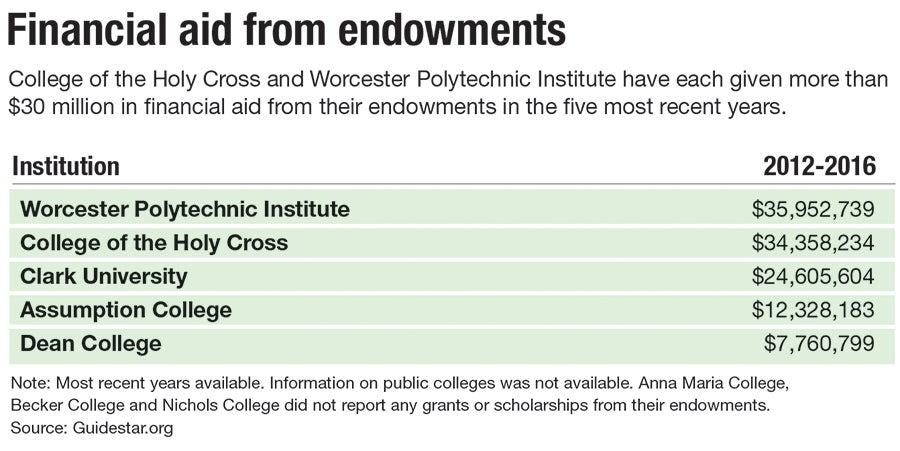

Holy Cross’ endowment has ballooned by $364 million in the last 15 years, and endowments at Clark University and Worcester Polytechnic Institute have expanded by more than $200 million each, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. That has helped pump millions more into student financial aid, as well as support for faculty positions and other areas.

Endowments aren’t the only source of financial aid. But nearly half of endowment spending supports financial aid, and for the largest endowments, a school’s ability to defray student costs becomes significant. Endowments can be a bragging point, a factor in college rankings, a consideration for presidential tenures, and a reassuring sign to prospective students and parents a college is on solid financial ground.

A new priority

Central Massachusetts colleges that used to treat endowments as practically an afterthought have been forced to make fundraising a high priority, including public institutions previously relying on state funding for the bulk of their income. That’s no longer the case, and schools have adjusted, including at Framingham State University, where today’s endowment of more than $40 million was $1.7 million in 2004.

“We were not nearly as active in fundraising in the past,” said Eric Gustafson, Framingham State’s vice president of development and alumni relations.

Donors to Framingham State have helped increase scholarships and cover the cost of what for students would otherwise be unpaid internships, he said.

“They really believe in our mission about making an excellent education affordable to everyone,” Gustafson said of the school’s donors.

At Worcester State University, Tom McNamara, the vice president for university advancement, remembers when the endowment was $170,000 about two decades ago. A state incentive program matched dollar-for-dollar any amount the university brought in on its own, helping to eventually grow the endowment past $30 million.

“At the time, it was significant in changing the culture of giving,” McNamara said.

Worcester State uses about 70% of what it draws from the endowment each year on financial aid, with the help of more than 400 individual scholarship funds for students.

“We’re giving so much more money than we ever could before for scholarships,” McNamara said.

The wealthiest gain the most

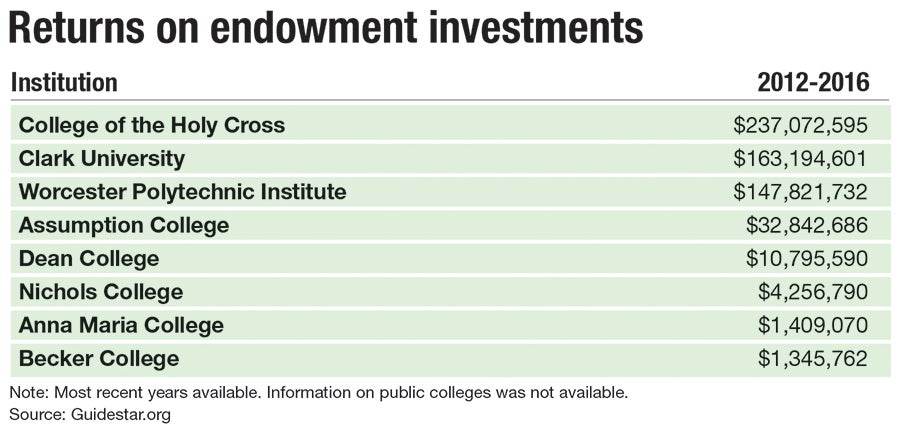

Colleges with the largest endowments to begin with have generally seen higher investment return rates than their smaller counterparts, according to a study this year by the National Association of College and University Business Officers and the financial services company TIAA.

Those schools have bigger investment staffs and a greater ability to make longer-term investments in areas like private equity and hedge funds, said Ken Redd, a senior director for research and policy analysis at the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

In Worcester, ambitious fundraising campaigns have exceeded expectations.

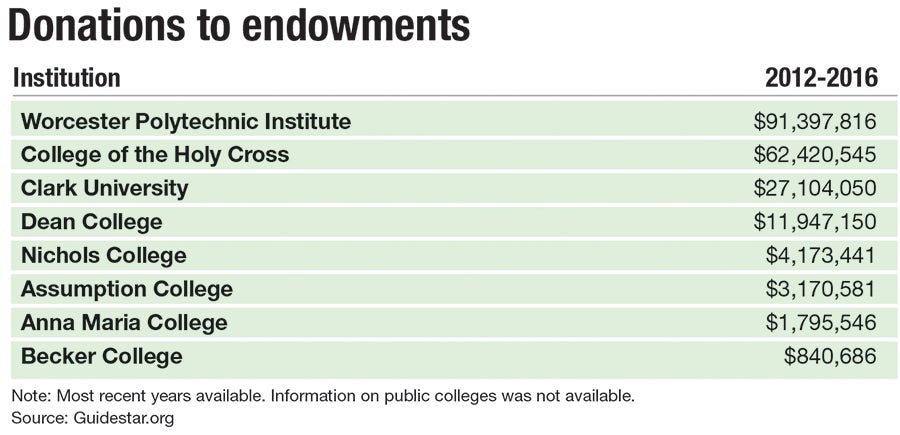

Holy Cross is nearing a goal of $400 million in a campaign in which major gifts have included $40 million from alumnus John Luth and his wife, Joanne Chouinard-Luth, for an athletics and recreation center now under construction. A $25-million donation in 2013 from Cornelius Prior Jr., a 1956 graduate, started the college’s plans for a $92-million arts and performance building.

WPI launched a $200-million fundraising campaign in 2012, and ended up with $248 million, or nearly 25% above the school’s goal, with 45 gifts of $1 million or more. That included a $40-million gift for scholarships from Robert Foisie in 2014. Foisie, a deceased 1956 graduate, gave more than $63 million in total to WPI.

UMass Medical School had a successful $250-million fundraising campaign started in 2016 and has 20 new endowed faculty chairs since Chancellor Michael Collins was appointed in 2008. Clark launched a $125-million fundraising campaign in 2017, and hit that target almost two years earlier than anticipated.

Mixed results, and potential danger ahead

The smallest endowments in Central Massachusetts have benefited from investment returns and donor giving, too.

Anna Maria and Becker have two of the region’s smallest endowments at each just over $5 million. But both were well under $1 million 15 years ago.

Becker has made it clear to potential donors how far their money can go for the 1,800-student school, said David Ellis, Becker’s executive vice president and CFO. Much of the contributions it receives go directly to financial aid, not to the endowment, he said.

“They want it put to use now,” Ellis said of aid benefiting students.

Despite the significantly larger endowments at those and virtually all colleges, investment returns have generally not met expectations, according to the National Association of College and University Business Officers study. In the last decade, colleges have averaged a 5.8% return, short of a 7.2% target set to keep up with inflation and costs.

“They got very gun-shy in the wake of the Great Recession,” Latham said. “Understandably so, but it caused them to miss out on the market.”

Public colleges in Central Massachusetts have generally played it safer. Framingham State reviewed its investment and spending policies a decade ago, and generally spends 5% of its endowment while seeing returns averaging 8.5%, said Dale Hamel, Framingham’s executive vice president.

Worcester State saw its endowment rise by 13% during the Great Recession, and has taken a low-risk approach even during a bull market, McNamara said.

“We’re prudent in looking at our long-term growth,” he said.

Becker has put its entire endowment in companies it says are socially responsible, such as those prioritizing public health or the environment – a move Ellis said was done largely with the college’s mission and its students in mind.

“The students coming to us now are very different than 20 years ago,” he said.

The move has also sheltered Becker’s endowment from market volatility.

“We transformed it to cushion it against the high highs and the low lows,” Ellis said.

Conservative management may be necessary in the coming years if endowments fall sharply in a recession. Economists still generally do not predict a downturn this year but potentially in 2020.

WPI, for example, saw its endowment shrink by roughly $113 million, or 28%, during the Great Recession, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Endowments at Clark and Holy Cross each fell by 25%.

Another sharp drop in endowment could particularly harm smaller schools that already rely more on tuition revenue to give financial aid to those who need it, said Redd, the policy analyst.

“They just don’t have the resources to make up for financial aid,” he said.