Fithian, a 1987 Clark graduate, was chosen for the job at the Worcester school in January, when he spoke of the importance of listening to the community’s needs and facing bold ideas.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

David Fithian could hardly have faced a more challenging first semester starting out his term as president of Clark University.

Fithian, a 1987 Clark graduate, was chosen for the job at the Worcester school in January, when he spoke of the importance of listening to the community’s needs and facing bold ideas. Then the coronavirus pandemic hit. Later, the campus was faced with racial equality protests and made headlines when it broke ties with the Worcester Police Department.

For Fithian, the pandemic in particular forced him to quickly form collaborative relationships with presidents of other nearby colleges and form operational plans with a Clark administration he was only just starting to get to know.

“There are many ways for which the intensity and immediacy of needing to plan for a number of different scenarios for fall, starting back in the spring, actually, for me as an incoming president were helpful in bringing the leadership team together, and giving us something to focus on that we had to accomplish as a group,” he said in a wide-ranging interview.

“I don’t bemoan the fact that I became a president under these circumstances. Would I choose these circumstances? Of course not. But there is a way in which it really focused the work right away.”

Thrown off track

Before Fithian even began officially serving as Clark’s president on July 1, he was already leading its emergency response committee. His predecessor, David Angel, was leaving Clark after a decade as its president, and giving Fithian a head start would enable the administration to better prepare for a fall in which there were lots of unknowns.

Regular meetings among area college presidents have been critical in developing the best pandemic response plans, said Jeanine Went, the executive director of the Higher Education Consortium of Central Massachusetts.

“I believe his openness in sharing ideas and plans has helped him to acculturate quickly,” she said.

Virtually everything else about Fithian’s first semester as Clark’s president would have to be pushed aside.

He did hire a vice president to help on strategic planning, and Fithian has laid out five areas of focus and potential investment – he wouldn’t make their details public – as he hopes Clark can take ambitious steps to better differentiate itself once the pandemic passes.

“We’re off and running with that work,” Fithian said. “I’ve shared my hope that we’d be open to greater ambition.”

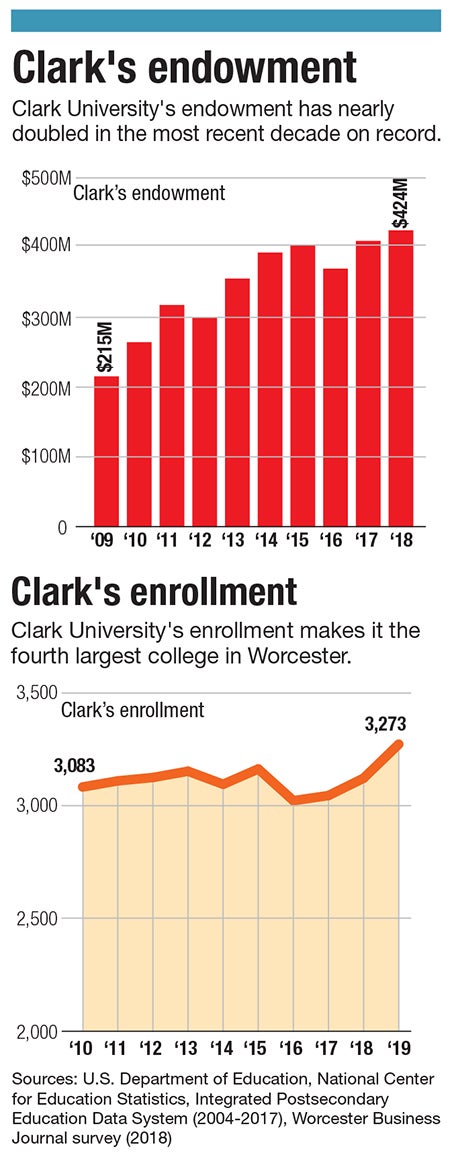

Fithian quickly adds a push for more ambition is no slight to his predecessor or existing administrators or faculty. It's through Fithian’s experience in serving as a dean at Harvard University in Cambridge and as an executive vice president at the University of Chicago that Fithian better understands where Clark can carve its niche. Clark doesn’t have nearly the financial heft or brand name those schools have, yet its endowment stands at more than $400 million and the school spans both research and liberal arts focuses. Its relatively small campus and student body allows for a city living experience for students without feeling lost.

“The size and scale of Clark allows that to be pretty compelling,” Fithian said. “We need to take this moment early in my presidency to really think about all that there is to work with, to look for untapped potential, to really develop a deeper, greater sense of, what does it really mean to be educated at Clark?”

Racial unrest

The school made headlines for cutting ties with the Worcester Police Department after four Clark students were arrested in a protest over the summer about racial equality. At the same time, Clark’s Black Student Union raised concerns about racism on campus and what members said was a lack of the school prioritizing their concerns.

In the interview, Fithian addressed those issues in broader terms.

“What are we about? We’re about preparing students,” he said.

“If we can’t have those conversations here then we’re not really preparing our students to make their way in the world successfully,” he continued. “That’s been a growing concern for decades, how colleges have come to be less tolerant to ideas that aren’t the prevailing ideas. I think that’s a dangerous and risky thing for colleges, to try to shut down ideas that are unpopular.

“That’s a complicated topic,” Fithian concluded, “but I do really believe freedom of expression on college campuses is under assault, and that has to be a core institutional value, to continue to fill our educational mission for students.”

Keeping the pandemic at bay

On the pandemic, Clark had more unquestioned success. Of roughly 85,000 tests conducted between mid-August and early December, 44 came back positive – about half of 1%.

In a one-month stretch, the campus had not a single positive result. It wasn’t until the week before Thanksgiving – when the campus was about to close for the semester and move online anyway – that Fithian decided to shift to online learning early. Seven tests came back positive in one day, just as the area’s virus numbers were beginning their sharp rise.

Fithian had students, faculty and staff sign a compact called the Clark Commitment, a pledge to keep the campus and neighborhoods safe.

“No one took it as an imposition that I know of,” Fithian said. “Everyone really did take it to heart.”

He credits students most for keeping the pandemic largely away, as well as the Broad Institute in Cambridge, which helped it and many other colleges quickly turn around test results. The spring semester has been pushed to a late February start to avoid the winter surge in cases.

The pandemic’s aftermath

The pandemic accelerated most campuses' adoption of online learning, and in the long term, courses that are fully online or mix in-person and online components are likely here to stay, Went said, because of the flexibility they offer.

To Fithian, the pandemic also demonstrated the value of an in-person education, and having people together on campus, learning and living together.

“We had a real moral imperative that some students needed to get back to campus, and we needed to make sure that we made that possible in the safest way,” he said.

Fithian isn't among those who think online courses will replace campus life.

Clark officials' sense in talking to students who’ve deferred is that many will come back – as soon as for the spring semester.

And despite the pandemic forcing athletics, clubs and other campus events to be canceled, the school has found a desire to be on campus hasn’t disappeared.

“We think about it all the time. What is the future of higher education, and what will it look like in five, 10 or 20 years? I think the pandemic has sharpened that forward look,” he said. “I would say it’s still unclear, honestly. We’re not through it enough to know.

“I really believe if distance learning becomes more of a feature, I don't think it’ll completely take over,” he said. “There’s something about that in-person, direct contact that’s incredibly important, and incredibly powerful from an educational aspect, and really important from a social, psychological aspect for students.”