People with intellectual and developmental disabilities are often unnecessarily left out of the workforce because of barriers they face, including those imposed by the federal government.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Jennifer Varnet works high above Main Street in Worcester, at the city’s oldest law firm: Fletcher Tilton. She prepares and scans files as part of a push to get literal tons of paperwork into online archives.

In her spare time, she enjoys completing puzzles and swimming. She earned first place in the 50-meter butterfly, third in the 50-meter freestyle, and fourth in the 4x50 meter relay in the Special Olympics Massachusetts this year.

Yet, she is only able to work one day a week. Like millions of Americans, Varnet has a developmental disability and faces barriers to gaining full employment, both logistical and government-imposed bureaucratic obstacles.

As unemployment rates locally and statewide hover around historic lows at 3%, Central Massachusetts nonprofits and businesses are working to help people with disabilities gain jobs, in ways beneficial to both employees and employers.

“We can be the workforce solution,” said Mary Heafy, president and CEO of The Arc of Opportunity in North Central Massachusetts, an organization which offers a variety of services for people with disabilities.

Work provides a sense of identity for people, and it’s no different for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities, Heafy said. It’s important for them to have an identity beyond their disability.

“What, at a chamber of commerce event, might we exchange with each other first?” asked Heafy. “It’s our work lives, our professional lives. As adults, that’s often a nice opening to get to know people.”

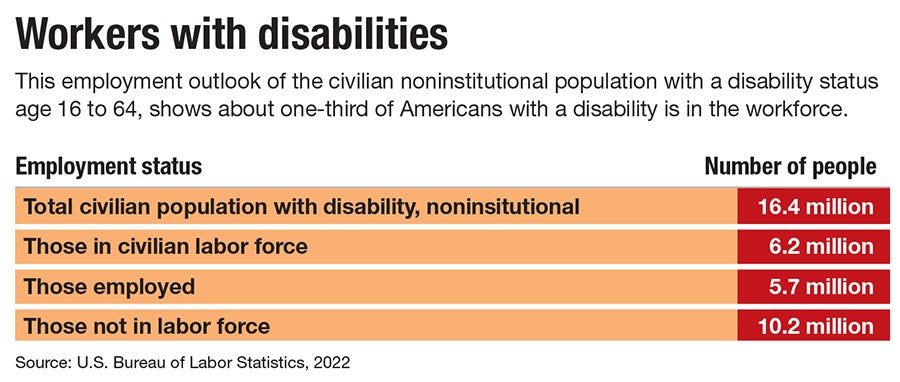

While employers face staffing shortages across multiple industries, people with disabilities are being overlooked as part of the workforce, she said. The national unemployment rate for people with a disability is 7.6%, but the labor force participation rate is 23.1%, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If more people with disabilities can become part of the labor force, that will provide millions of potential workers for U.S. companies, Heafy said.

Employee benefits

Varnet enjoys her job at Fletcher Tilton because she has a lot of friends there, and enjoys company events like this summer’s office trip to see a Worcester Red Sox game. She takes pride in completing the tasks she’s learned and likes the respect she gives and receives from her coworkers.

“A job is more than just a paycheck,” said Theresa Varnet, Jennifer’s mother, an attorney who works with Fletcher Tilton. The job gives Jennifer a sense of fulfillment, provides a social outlet, and enhances her self image.

The benefits of Jennifer Varnet’s employment is a two-way street, said Wilma Vallejos, Varnet’s supervisor and the trust and estate planning manager at Fletcher Tilton.

“She’s great for everyone in the office,” said Vallejos, “She brings a good energy to everyone around her.”

Varnet has an excellent memory and retains what she’s learned once she learns a new skill. Vallejos appreciates Varnet’s ability to work independently and maintain her own workspace.

Frederick Misilo, chair of the trust and estates practice group and shareholder at Fletcher Tilton, said Varnet enjoys tasks other people might find repetitive or tedious, and he is impressed with her punctuality and diligence.

Misilo is a long-time advocate for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. He was the chairman of the board of the The Arc of the United States, the national organization under which The Arc of Massachusetts and The Arc of Opportunity of North Central Massachusetts falls.

Employer benefits

Theresa Varnet said employing people with disabilities can be seen as a benefit to job candidates of all abilities. She recalls when Jennifer was working for Westborough accounting firm AAFCPAs, a job candidate at the firm saw the company’s employment and treatment of Jennifer as a deciding factor in choosing to work for AAFCPAs.

To provide employment for Arc program participants, the nonprofits partners with local businesses like Hannaford supermarket, office furniture manufacturer AIS of Leominster, Ocean State Job Lot, Great Wolf Lodge in Fitchburg and Minnesota-based medical manufacturer Bio-Techne, which has a facility in Devens.

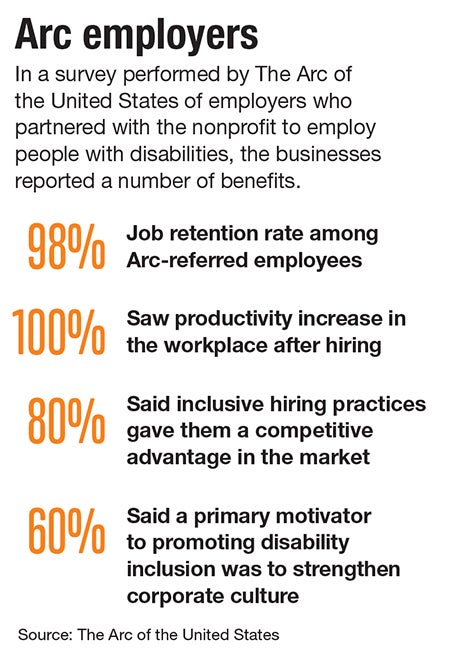

For the businesses, such partnerships are not charity, but a mutually beneficial employment relationship, said Madeline Merchant, division director of community-based day and employment supports at the Arc of Opportunity in North Central Massachusetts.

“They are not hiring the disability,” said Merchant. “With the right supports, employers can expand who they’re looking at to fill jobs.”

Incentives are available for employers to hire people with disabilities, Merchant said. For example, the Internal Revenue Service offers a Work Opportunity Tax Credit for employers who hire individuals in targeted groups.

Small businesses could be eligible for a Small Business Disabled Access Credit of up to $5,000 to make their spaces more accessible to workers with disabilities. This could include amenities like an automatic door, or an audio device for an employee who needs assistance to hear.

People with disabilities are among the targeted groups that employers who seek federal contracts are supposed to hire, Heafy said. These employers are expected to have people from targeted groups making up 10% of their workforce.

But, Merchant emphasized, employers should focus on the abilities people bring to the job, rather than financial incentives or public relations gains.

Workforce obstacles

The most significant barrier to people with disabilities achieving employment – particularly full-time employment – are the limitations the Social Security Administration places on people receiving disability benefits. A person receiving Supplemental Security Income has a cap of $2,000 on the assets they can own while receiving benefits. This cap was set in 1979.

There is a limit on how much income they can earn while receiving the benefits.

These means-tested benefits go beyond income received from Social Security and extend to Medicaid. If someone loses their SSI benefits, then they can lose access to certain government benefits, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, Section 8 housing vouchers, and fuel assistance.

In Massachusetts, recipients can make up to $42,000 without losing Medicaid benefits, but those in other states are not so fortunate, said Theresa Varnet.

Workers with disabilities lose a dollar from their SSI checks for every two dollars they earn. But they can also account for disability-related expenses incurred while working, like for para transportation, allowing then to keep that portion of their benefit check.

These means-tested benefits mean Jennifer can only work a limited number of hours per week. While she might prefer to get into the office more often, she only works one day a week because she has to arrange for transportation privately.

Transportation is another barrier to working with a disability. While the Worcester Regional Transit Authority will arrange transportation for Jennifer to get to a doctor or hairdresser’s appointment, it will not help her get to work, Theresa Varnet said. She is going to have to miss two weeks of work this month because she can’t get a ride.

Heafy, whose organization serves rural areas in Northern Worcester County as well as cities like Fitchburg, Leominster, and Gardner, said transportation can prove to be a barrier, especially if the worker requires para transportation. In areas served by public transportation, para transportation can cost $8 a day to and from work, versus $1.25 for the bus.

But, for people who live in a rural area, who may need to take a taxi to work, it can be very expensive, said Heafy. The people served by public transportation can count the difference between bus fare and para transportation as a disability-related expense, while because no alternative exists in the rural area, those workers cannot.

Then there is the bias of low expectations that these workers fact. Some people see them as the eternal child they’re not willing to babysit, said Theresa Varnet.

Jennifer is an adult. She lives on her own with limited help from a live-in caregiver. She sets her own schedule to do her household chores and picks out her own wardrobe, which she knows must be appropriate for work in a law firm. Her enthusiasm for Fletcher Tilton is evidenced by her smile, which brightens the room when she talks about her job and her coworkers.