To reach vulnerable populations, healthcare providers find news ways to deliver care where patients are most likely to need treatment.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The Spectrum Health Systems van often sits in the parking lot at 1023 Main St. in Worcester’s Main South neighborhood, currently next to nothing more than an abandoned American Legion post, bought by the company in August.

But every day, an average of 110 members of the community enter the van, receive a dose of methadone, and within minutes they are back to their lives and able to function for the day.

The van is Spectrum Health’s mobile service for opioid-use disorder treatment, a program the mental health and substance abuse treatment provider launched in late February, offering same-day treatment seven days a week for those seeking medication-assisted opioid recovery treatment.

It is one of several moves by the Worcester-based provider to build out its operations. Spectrum will move its headquarters to Westborough in 2024, creating a hub including an intake center for patients to receive comprehensive clinical assessments, and the healthcare provider is opening a peer-to-peer recovery support center in Southbridge.

Since February, clinicians working out of the van have seen nearly 350 individual patients come through.

“We realize we need to start thinking about new ways to do this,” said Heidi DiRoberto, regional executive director for Spectrum Health Systems.

The new approach of bringing treatment into the community has been a success so far, DiRoberto said.

In the fight against opioid addiction, healthcare providers need to be constantly reevaluating the ways they are delivering treatment, said Kristin Nolan, Spectrum’s chief behavioral health officer.

“We are constantly renewing our curriculum, because addiction treatment changes all the time,” Nolan said. “It’s so important to deliver service in such a way that will speak to the patients”

Changed government regulations made treatment options like a mobile van feasible, said DiRoberto. Federal regulations long made it a challenge to administer doses in non-traditional settings, due to a pervasive concern of misuse, but in March 2020 the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in March 2020 loosened regulations, enabling more outpatient methadone treatment options.

The target population for treatment at the van is individuals who have never accessed any kind of opioid treatment. Since the February start, 60 of the patients started medication-assisted treatment at the mobile unit as the first point of contact. While the balance started treatment at a brick-and-mortar Spectrum location, they now come to the mobile unit for easier access.

The retention rate for patients is approximately 70%, she said.

“That’s huge,” said DiRoberto.

The 60 who started at the van were individuals who likely never would have had treatment at all otherwise, said DiRoberto. Much of the population coming to the mobile unit are unhoused. People who can access brick-and-mortar treatment centers have the means to travel there, while unhoused populations have trouble leaving where they currently are.

Spectrum is the third-largest addiction services provider in Central Massachusetts, with 569 employees in the region, according to survey data compiled by the WBJ Research Department. Spectrum generated $100 million in revenue in 2021 and has $87 million in assets, according to its most recent tax forms available on the nonprofit website Guidestar.

Opioid-related deaths are spiking

Part of the reason the mobile treatment facility is finding success in bringing patients in is because the services offered are desperately needed.

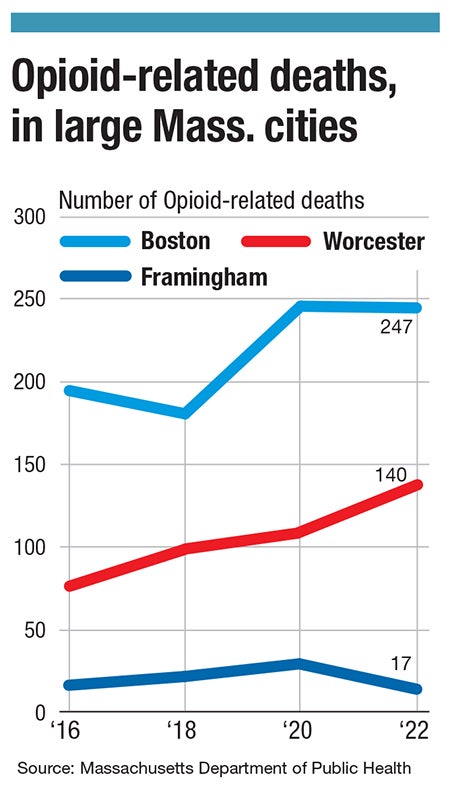

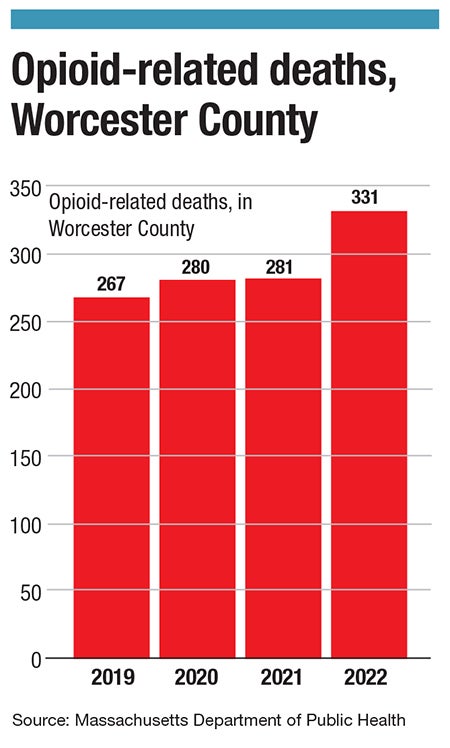

In Worcester County, opioid-related deaths increased by nearly 20% from 2021 to 2022, one of the largest upticks across Massachusetts, and one of the largest bumps up in the past 10 years. In the county, 331 individuals died from opioid-related causes in 2022, the largest number in the past 10 years of data from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Statewide, fentanyl was present in 93% of those 2022 deaths.

Fentanyl has been a game changer in the worst way for individuals suffering from opioid addictions, said Nolan. Its pervasiveness means it is often cut into other drugs, further endangering the population without their knowledge.

“We are often telling patients for the first time they've used it,” said Nolan. “They don't realize it’s in their system.”

Within the city of Worcester, there has been an even greater increase in deaths. The city saw 140 opioid-related deaths in 2022, a 33.3% increase since the year prior. It is the highest total number of opioid-related deaths in the city for a single year, according to DPH data.

Opioid-use disorder disproportionately impacts disadvantaged groups, and racial minorities represented a large proportion of opioid-related deaths in Massachusetts. Statewide, opioid-related death increases are at the highest rate among Black, non-Hispanic residents, according to DPH data.

Among that group, the rate increased by 42% from 2021 to 2022, 36.4 to 51.7 deaths per 100,000 residents. The overall opioid-related death rate per 100,000 residents is 33.5.

Reaching struggling populations

New programs are looking to address issues of equity, said Dr. Matilde Castiel, commissioner of health and human services for the City of Worcester.

Castiel was instrumental in leading Worcester to open vaccine equity clinics across the city during the COVID pandemic and ensuring services remained open, particularly for residents suffering from the co-occurring opioid epidemic and mental health crisis.

She likens the opioid approach to what was done with the COVID-19 vaccine during the pandemic, wherein healthcare providers went out into the community to make accessing the vaccine easier and medical care less intimidating. There is a lot of mistrust of the system, said Castiel, and meeting people where they are helps to break that down.

“We are thinking about how to reach out to the members of the community that weren't getting to us,” said Castiel. “How do we go out and reach people not accessing the system?”

Bringing more patients in for treatment has the goal of reducing that fatal outcome statistic.

“Fatal outcomes are from people not in treatment. Those are the people we need to get to,” DiRoberto said.

Care teams at Spectrum are notified if individuals receiving treatment in their program have fatal outcomes. Those in active treatment are not among those reported to them, she said. People not receiving any kind of treatment are the most at risk for fatal overdose.

When compared, those receiving methadone treatment have a 59% reduced chance of overdose than those receiving no treatment, according to a 2018 National Institutes of Health-funded study in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Yet despite their effectiveness, the physical barriers to opioid-use disorder treatment, like distance or lack of transportation, aren’t the only thing preventing would-be patients from seeking medicated assistance.

“There's a stigma regarding every medication-assisted treatment out there,” said Castiel.

Medication-assisted opioid-use disorder treatment recognizes addiction is a disease, which it is, said Castiel.

“When people are coming to us, they're no longer using to get high. They are using to get out of bed in the morning,” said DiRoberto. “They’re using to function.”

Methadone helps with severe withdrawal symptoms, so patients can function, participate in therapy, work, and take care of their families.

“Folks medicating every day is the best thing they can do,” said DiRoberto.