When Kate Tobiasson, a Westborough resident who spent nearly 15 years working as an English teacher at three different Central Massachusetts school districts, was about to give birth to her first son in February 2013, she had fortunately saved enough accrued paid time off over several years.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When Kate Tobiasson, a Westborough resident who spent nearly 15 years working as an English teacher at three different Central Massachusetts school districts, was about to give birth to her first son in February 2013, she had fortunately saved enough accrued paid time off over several years.

Her accrual, plus fortunate timing with the school calendar, provided her seven weeks with her first baby.

But in 2016, when she was pregnant with her second son, she wasn’t so lucky.

Taking care of both herself and her first child, who was prone to frequent illness, she ran out of paid time off by the time she was ready to give birth.

“I ended up taking about four weeks of unpaid time,” Tobiasson said.

To rub salt in the wound, she then had to write a check to the district, paying for the health insurance coverage she maintained during those four weeks without pay, which she said she felt fortunate her family was able to afford.

With a second child to care for, the difficulties associated with minimal paid time off options intensified. Eventually, she gave up.

“I always felt like I was shorting someone, whether it was my husband who owns his own business and was taking 10 days off a year, or if it was my daycare lady who was going out of her way [to help], and my colleagues,” Tobiasson said, describing times she attended work with a fever, a concussion, or other illnesses, either because she needed to save time off, or she didn’t have any left. “I just felt like I could no longer continue to ask people to cover for me.”

Tobiasson left her teaching career after the district she worked for denied her request to drop down to part-time work.

On Jan. 1, Massachusetts’ new paid family medical leave law went into effect, intending to help situations like the one Tobiasson faced or other family medical situations.

Under the state law – one of nine like it throughout the nation – workers are guaranteed 12 weeks of family leave to bond with a newly born or adopted child, 20 weeks of medical leave for a serious health condition, and 26 weeks of leave to care for a sick or injured family member who has or is serving in the military. The final leg of the law, which allows for leave to take care of a sick family member, will go into effect on July 1.

For workers, and particularly women, the law’s implications cannot be understated. U.S. Census data indicates one in five women quit their jobs before or shortly after having a baby, and, according to 2018 data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 17% of civilian employees in the U.S had access to paid family leave.

Separately, a 2012 study by the Center for Women and Work at Rutgers University found women who took paid family leave were 93% more likely to return to work in the nine to 12 months after having a child and 54% more likely to report increased wages in their first year postpartum than those who take no leave at all.

The Boardroom Gap

Although it is too early to tell what the long-term impacts will be of paid family leave on the Central Massachusetts economy, evidence from other countries with similar policies shows paid time off increases female participation in business leadership positions. A 2017 study by the American Economic Association in Tennessee shows when new mothers are away from paid work for longer periods, the less likely they are to be promoted.

Through its now four-year-old The Boardroom Gap investigative series, Worcester Business Journal has tracked the gender diversity of the executive suites and boards of directors at 75 prominent Central Massachusetts business organizations. This year, the percent of female leaders reached its highest in the four-year investigation – 37% – a three-percentage-point increase from last year.

The investigation, which examines 1,600 executives and leaders in Central Massachusetts, found the number of companies with no women in the executive suite or on their boards – so-called zero-zeros – increased from seven to eight in the last year. Of the 75 organizations, 11 are led by women, which is the same as last year.

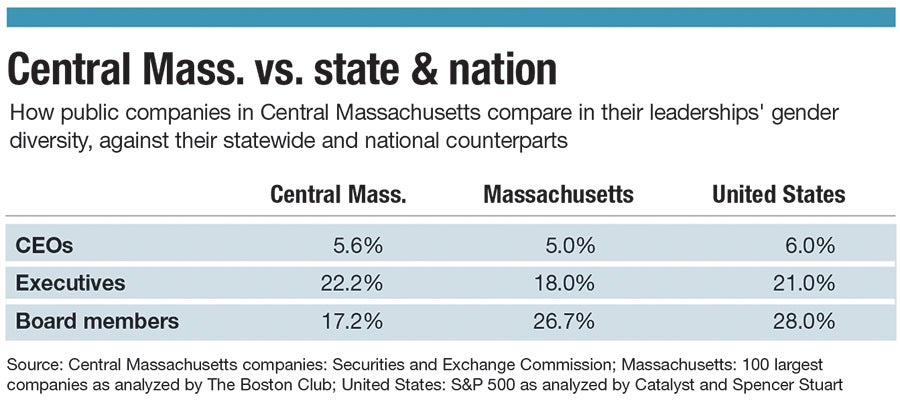

Central Massachusetts outpaces the entire state in having women CEOs at public companies – 5.6% vs. 5% – although both trail the national average at 6%. In having women on boards of directors at those companies, Central Massachusetts (17%) is behind both the state and national averages by 10 percentage points.

The leadership gap is lower in certain industries. Women make up 53% of the region’s social service nonprofit leadership, and 41% of leadership at area colleges, according to The Boardroom Gap data. Those numbers dip into the 30s at private corporations, healthcare organizations and financial institutions, and then down to 19% at public companies.

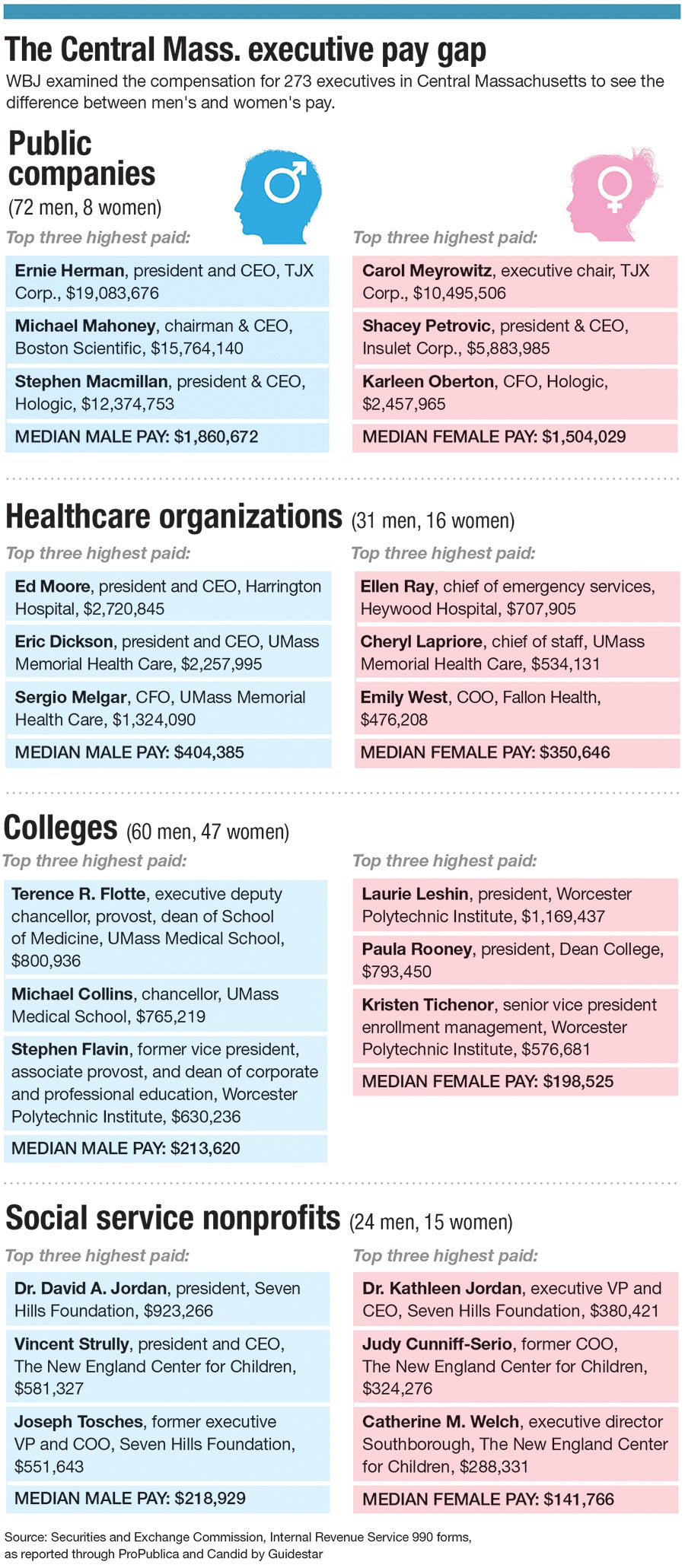

Women’s pay, on average, remains below men at these Central Massachusetts business leadership positions. At Central Massachusetts social service nonprofits, for example, men executives earn a median income of $218,829, whereas women leaders are paid $141,766. The median pay for male leaders at the region’s public companies is $1.9 million, compared to women executives, whose median income is $1.5 million.

Although it’s too early to measure the new Massachusetts paid family medical leave law’s impact on women who hold or aspire to leadership positions in their respective fields, it stands to reason equipping mothers with the tools and resources they need to take care of their families and protect their careers immediately upon giving birth could, in the long run, allow for more women to ascend the corporate ladder, or at least more easily retain leadership positions they already have.

Employers & paid leave

PFML works by taxing wages at a rate not exceeding 0.75% of an employee’s eligible weekly pay, and is paid by the employee and/or their employer. Those who use the PFML program receive benefits from the Family and Medical Leave Trust Fund, based on a percentage of their income, up to $850 per week.

Although the PFML program marks a significant change for employers, outside of pandemic-related financial stressors, Worcester area businesses have largely taken the new policies in stride, said Alex Guardiola, the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce’s director of government affairs and public policy. The chamber, he said, has hosted webinars to prepare business owners for the steps they need to take to comply.

“They’re a little nervous in the sense that they don’t want to misstep or violate any kind of regulations, whether it be on the payment side or the leave availability side,” Guardiola said.

By and large, companies are cautiously optimistic about the law’s implementation, he said.

There are many reasons why women might leave their jobs, or the workforce, more broadly, after having children. Among them are the high cost of childcare, which drives many families to make the difficult decision for one caregiver to temporarily or permanently leave their jobs; lack of workplace flexibility once mothers return to work; or, an extension of that challenge, feeling like one has not been given enough time to bond with their new child or adjust to adding a new family member to their household.

While PFML is not a catch-all for every challenge faced by every working family, it does provide a social and economic buffer to allow working parents to make informed decisions about what is best for their individual families, ostensibly easing at least some of the pressures that go into deciding when and how to keep working.

Those left behind

While the new PFML was designed to help professionals like Tobiasson, the Westborough teacher, balance career and family responsibilities, she would not have been eligible for the benefits.

Automatically exempt from the program are all municipal employees, unless individual towns and cities choose to opt into the program through their respective governing bodies, leaving leave policies up to individual and/or union negotiation.

Among the municipal employees who are not guaranteed PFML benefits under the law are the roughly 75,000 full-time teachers the state’s Department of Education reports employing.

Municipal employees, including teachers, weren’t necessarily left out of the state’s PFML legislation intentionally, according to Raise Up Massachusetts, the nonprofit that coordinated the PFML ballot initiative ultimately rescinded in lieu of a legislative compromise.

Leave for municipal employees was not debated as part of that process because it fell into a legal grey area, said Andrew Farnitano, a spokesperson for Raise Up.

“There’s some constitutional restrictions on the state’s ability to [institute] an unfunded mandate,” Farnitano said. “The ballot question we proposed would not have applied to municipal workers.”

The City of Worcester, when asked whether it had taken any action or had any discussion about whether or not to opt into coverage for its employees, said through spokesperson Walter Bird the city has historically “provided excellent paid leave benefits to their employees through negotiated collective bargaining language that allows us to administer leave benefits in a fair and balanced way specific to the needs of each employee group.

“The PFML also imposes additional costs to both the employer and the employees through a payroll tax, which would place an unnecessary burden on our employees and taxpayers,” Bird said.

As for Tobiasson, after she left her teaching job, she used her experience as a freelance writer to pivot to an editing job. Six months later, however, the pandemic hit and that gig, too, fell through. She now works as an insurance agent at her husband’s company.

“I finally feel like I have a job where I have balance and the ability to focus where I want to when I want to,” she said.

Tobiasson underscored she did not believe the districts she worked for actively worked against her, but they were doing what they could with the resources they had.

“I'm certainly entertaining returning to teaching, because like I said at the start, I really did feel moved and called to teach,” Tobiasson said. “But I can't do that while I have small children at home.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story contained an incorrect chart saying the total compensation for Tracy Barlok, vice president of advancement at the College of the Holy Cross, is $866,053. The correct amount is $421,483.