Worcester, like cities around the rest of the country, is in the midst of a cultural reckoning.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Worcester, like cities around the rest of the country, is in the midst of a cultural reckoning.

Bolstered by grassroots organizing, human service nonprofits and other concerned citizens, city leadership and stakeholders are engaging residents in conversations about an array of deep-seeded inequities, many centered around and rooted in all of the ways systemic racism is woven into the fabric of everyday life in Central Massachusetts.

In the past year, these conversations have centered around issues like police brutality against the city’s Black and Hispanic communities, as well as racial inequities in the city’s schools and on the school committee. These are community-oriented issues: Children typically attend schools closest to them based on district mapping, and neighborhoods of color around the U.S. are demonstrably and statistically over-policed.

A 2019 Pew survey found, for example, Black adults were five times more likely than white adults to report they were unfairly stopped by police because of their race or ethnicity. And a 2016 Guardian database tracking people killed by police in the U.S. found 6.6 Black people per million were killed, compared to 2.9 for white people. That number was significantly higher for Native Americans, who were killed by police at a rate of 10.13 per million people. And those, of course, are just two data sets.

These types of racial injustices become community-oriented in more tangible, spatially-oriented ways when residential segregation is taken into consideration, particularly in homeownership between Worcester’s white and non-white residents. In that way, the community issue is literally concrete.

Since December, the Worcester Business Journal and the Worcester Regional Research Bureau have been jointly investigating racial discrimination in Greater Worcester on one of the key aspects of the American Dream: homeownership, which is one of the main ways to build wealth over generations.

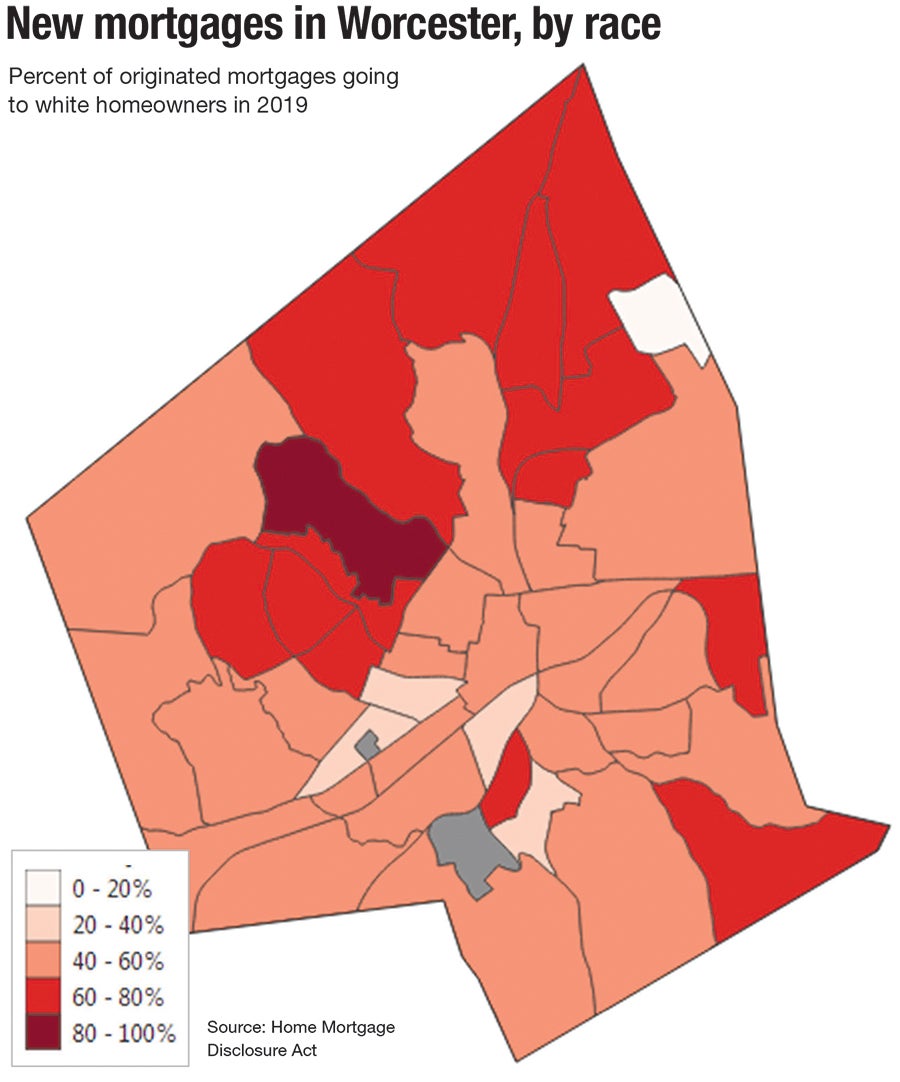

The WRRB-WBJ findings, using Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data in conjunction with U.S. Census Bureau statistics, confirmed what is easily anecdotally observable: The city of Worcester suffers from racial segregation on its northeast/southwest axis. In some of the city’s wealthiest, northwestern census tracts, owner-occupied houses are more than 90% white, compared to several pockets on the city’s east side, where that drops as low as 60% or less.

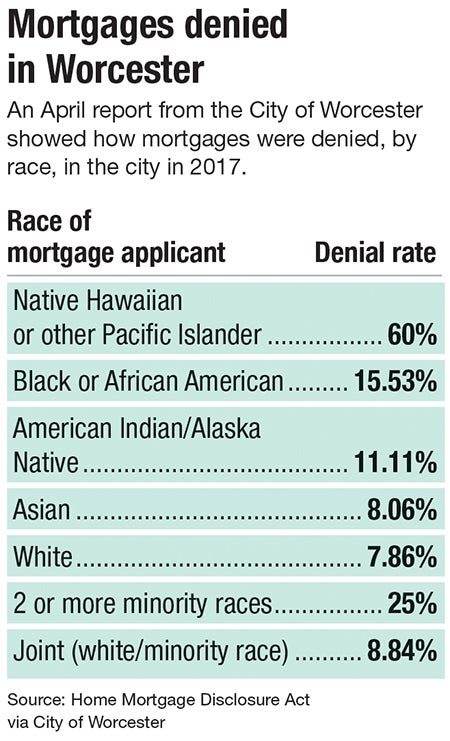

A separate April report from Worcester’s Department of Economic Development, compiled by the Central Massachusetts Regional Planning Commission and Barrett Planning Group of Plymouth, further found in 2017, non-white racial groups were denied conventional mortgage loans at rates sometimes twice as high as white applicants. While white mortgage applicants were denied at a rate of 7.9%, Black or African American applicants were denied at rates of 14.5%. The same data, when broken down by ethnicity, showed that Hispanic or Latino applicants were denied at a rate of 16.48%, while the white applicant denial rate remained at just over 7%.

The shoehorning of white wealth away into isolated pockets while the city’s residents of color are left, often to rent, in neighborhoods which are often disproportionately low-income, has made the self-proclaimed Heart of the Commonwealth a place where inequality and relative lack of access to basic resources are as embedded into the city’s culture as the neighborhoods themselves.

Dubious success

Ramon Borges-Mendez, an associate professor of community development and planning at Clark University in Worcester, said when considering the disparate homeownership rates and ethnic segregation in the city, it’s important to keep in mind that Worcester is a city of immigrants and refugees. These population groups move to the city at varying points in time and are integrating and setting down roots at different rates.

“Not all of them come at the same time, so they all face distinct circumstances when they hit the ground running,” Borges-Mendez said. “That’s what we call differential insertion, or differential integration or assimilation.”

To put that piece of the puzzle into perspective, the April housing impediment report from the city indicated Worcester is the largest resettlement city in the state, home to 30% of all refugees in Massachusetts. Accordingly, Worcester Public Schools reports more than 90 languages are spoken by children in the school system.

Still, Borges-Mendez said, what can’t be left out are the myriad of challenges the immigrant and non-white communities face when it comes to housing, and with it, the goal of eventual homeownership. Among those challenges are limited access to affordable housing, an option which would allow families to save up for a down payment on a mortgage.

“The City of Worcester, City Hall, doesn’t have particularly a very aggressive policy regarding the development of affordable housing,” Borges-Mendez said.

He pointed to developments in the city’s downtown, whose success he believes is dubious, and to the $160-million Polar Park public baseball stadium, which he said is increasing gentrification. Borges-Mendez, who lives downtown, gave himself as evidence, noting his monthly rent increased $400 this spring. He wondered who can shoulder such sudden inflations.

“A lot of people are going to stay behind, especially in the poor neighborhoods of the city… Over time, these populations are going to have a very hard time catching the windfalls of their house appreciation,” he said. “They don’t see any of that.”

As landlords, especially those around Polar Park, wait to see what kind of financial benefits they might receive from the area undergoing development – and gentrification – current residents are left to find new places to go. Where they end up as they are priced out of their homes remains to be seen.

“Either you’ll get further concentration into key areas, in terms of public housing, or segregated areas, but it’s very unlikely that at the current prices, you’ll be able to achieve some degree of housing integration,” he said. “It just doesn’t happen.”

That only serves to compound the challenges already in place around saving money for a down payment for eventual homeownership.

Student impact

Concentrating wealth and homeownership along racial and neighborhood lines has a trickle-down effect across the city, particularly for Worcester’s public school children.

While curricula and standardized testing may be uniform across a school district, racial and wealth segregation can and does produce wildly different school environments from neighborhood to neighborhood, said Katheryn McNicholas, an education consultant who studied at Clark, worked within Worcester Public Schools and helped compile a new report from Policy for Progress and EdBuild, a Massachusetts-based ideas and actions lab and now-shuttered nonprofit think tank.

“What you then come across, though, is you have students in your classroom who maybe are English language learners, so they need more time on assignments, or they need separate instructions, and we don’t have the resources to offer them translators or teacher aids,” McNicholas said. “Whereas the other schools, they’re moving right along because everyone speaks the same language or they have the resources to hire teachers who can translate.”

The 2020 report, Commonwealth Fault Lines, examined instances of segregation in schools around the state, including Worcester. The report found segregation in the state’s public schools has increased in recent decades, despite public perception it has decreased.

In Worcester, what ends up happening, McNicholas said, is public schools in the city’s lower-income areas, which disproportionately house its residents of color, end up disproportionately responsible for students with greater needs, whether because they are English Language Learners, have disabilities, or experience the myriad of challenges low-income students often have.

For reference, 2018 graduation data from the state’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education shows the four-year dropout rate in Worcester schools among English learner students was 10.2% and 6.3% for those considered high needs. For low-income students the dropout rate was 5.9%, and for Hispanic/Latino students, the largest nonwhite population group in Worcester schools, that rate was 7.9%. For white students, the dropout rate was 3.4%.

Put another way, a 2012 report from the Brookings Institution found, for students attending Worcester’s average top quintile school, 87% lived in owner-occupied housing. In the average bottom quintile school in Worcester, that number was 40%. Some schools, McNicholas said, don’t have a higher proportion of students who need greater assistance, allowing those schools to become high achieving easier.

“And then,” she said, “We have plenty of teachers who are really struggling to get through a lesson because they have to adapt to so many different levels of need within one classroom.”

And those challenges, McNicholas said, are absolutely more prevalent in Worcester’s lower-income – and more diverse – communities.