With cases rising sharply again, hospital officials planning for the winter are hoping that low hospitalization and death rates will continue, as a consequence of both a better understanding of the pandemic and a much younger population getting sick.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

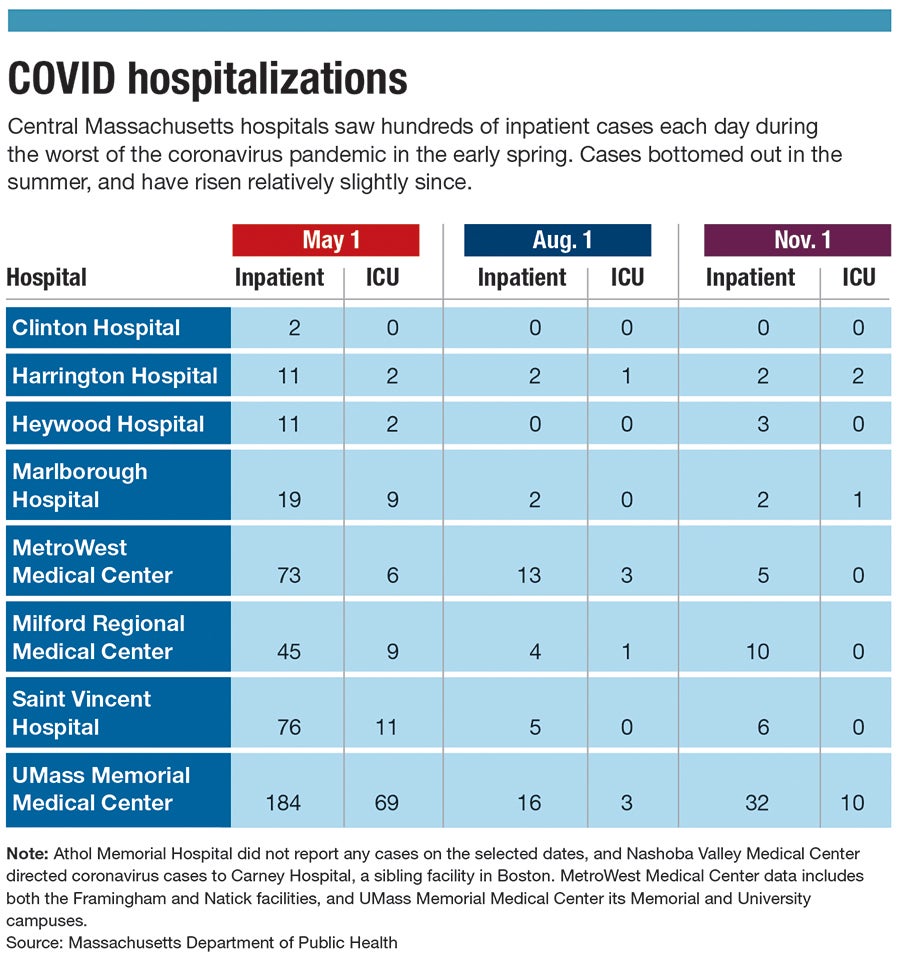

When the coronavirus pandemic peaked in Central Massachusetts in the early spring, hundreds of virus patients were in area hospitals, and dozens were in intensive care – so many that some hospitals had to repurpose ICU wings to make sure they had enough space.

In a two-month span, nearly 800 Worcester County residents died of the virus.

Now with cases again sharply rising since around mid-October, hospital officials are planning for a second wave this winter while hoping that low hospitalization and death rates – at least so far – will continue, as a consequence of both a better understanding of the pandemic and a much younger population that’s been getting sick.

“We’re watching the numbers very carefully and watching what’s going on in the rest of the country,” said Dr. Michael Gustafson, the president of UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester.

UMass Memorial is working with state officials to open a field hospital at Worcester’s DCU Center in early December with a plan for 240 beds, adding extra capacity for area hospitals as was done during the spring surge.

Better knowledge, preparation

Hospital officials said they’re optimistic this winter won’t be as bad as the initial wave in Massachusetts.

One important change is largely who is getting sick today, said Dr. Vinod Mohan, the infectious disease specialist at Heywood Hospital in Gardner. It’s far more likely to be younger people, who generally have lower risks of getting very sick or dying from the virus.

Today, 20-somethings in Massachusetts are testing positive at rates more than seven times higher than those who are 80 or older, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

That’s a stark departure from the spring. On May 1, for example, residents 80 or older were the second most common age group to test positive, slightly behind those in their 50s. Younger residents weren’t nearly as likely to catch it, and colleges having sent students home early for the spring semester – unlike many colleges today holding at least some in-person classes – kept transmission rates for younger people low.

Those 80 or older were more than twice as likely as any other group to be hospitalized in the spring, and almost five times as likely to die as any other group. Even today, the average age of a hospitalized patient is 67, and the typical death is in someone age 80, according to state data.

Hospital officials are encouraged by a better knowledge of how the virus works and how patients can be treated.

Health providers can now give remdesivir, an antiviral medication, or convalescent plasma, which comes from the blood of recovered patients and helps those fighting the virus. Researchers have been eager to share any discoveries they’ve made, said Dr. George Abraham, the chief of medicine at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester.

“Usually, the scientific community can be possessive of its information and not be as willing to share,” he said.

The Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association, a membership group of the state’s acute-care hospitals, has been helping to coordinate a response with daily calls among hospital CEOs.

“They’re certainly ready,” Steve Walsh, the association’s president and CEO, said of hospital leaders. “It’s a really talented group, a really passionate group. They want to put their patients first and their community first.”

Coordinating plans

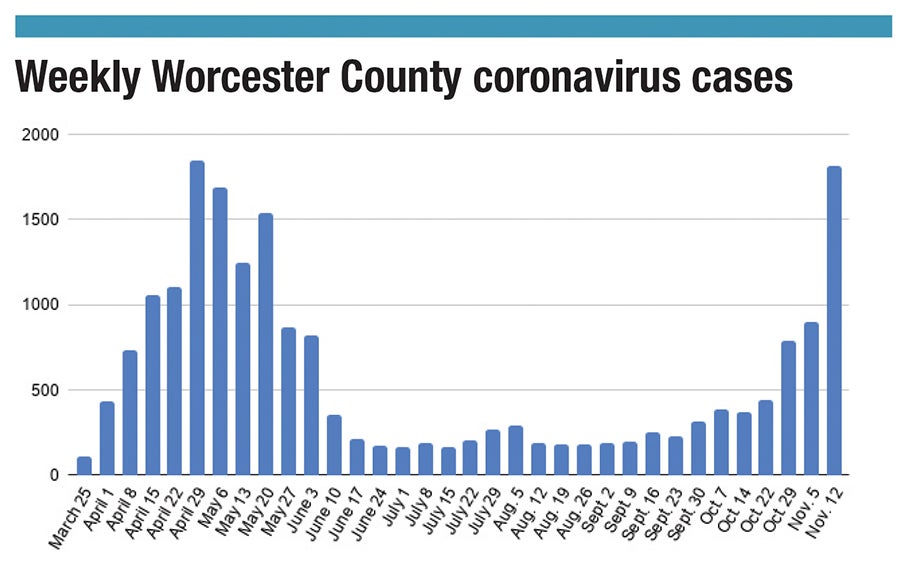

Cases in Worcester County peaked in late April, with a one-week stretch with more than 1,800 new cases. Deaths peaked a few weeks later, with 136 in a one-week period in May.

A hospital bed space crunch in the spring was so severe the convention center space at Worcester’s DCU Center was set up as a field hospital for less-severe cases and to house some homeless residents who would otherwise be at an especially high risk of catching the virus.

Elsewhere, UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester moved some intensive care beds to create a contiguous area for treating coronavirus patients. MetroWest Medical Center indefinitely called off a plan to eliminate acute care services at its Leonard Morse Hospital in Natick, and Milford Regional Medical Center created a temporary 3,800-square-foot facility at the back of the hospital to accommodate emergency department patients.

Hospital executives generally don’t expect a repeat of that.

MetroWest is moving ahead on plans for remaking Leonard Morse Hospital, for example. UMass Memorial has a new large warehouse for storing personal protective equipment, including hand sanitizer and wipes, and has enough to last a significant surge spanning three to six months. Other hospitals are also ready with plenty of PPE, Walsh said, with suppliers having enough time over the summer to catch up and make enough for the colder months.

But after cases bottomed out over the summer, they’ve been steadily on the rise since, and especially since around mid-October. With few exceptions, each week since that turning point has brought a new high since May.

In just a two-week stretch – the first week of November to the second – cases roughly doubled in the city of Worcester, across Worcester County and in Massachusetts. New daily cases nationally surpassed 100,000 for the first time on Nov. 4, and they’ve topped 150,000 a day on many days since then.

UMass Memorial leaders reviewed what worked well and what didn’t, and used those findings to plan for this winter. At Saint Vincent, weekly leadership meetings have ensured coordination, and a constant eye on its stockpile is monitoring usage rates and how long a supply remains under different scenarios.

The latest surge has not caught hospital leaders by surprise, but they are ready – and hoping that they’re taking precautions that won’t be necessary. One advantage from the spring – with help coming from states less affected at the time – won’t be available now, with the virus hitting many states far worse this fall than Massachusetts.

Officials are cognizant many people have tired of having to stay home or might be less careful than they used to be, and this less-vigilant attitude could be harmful. Healthcare workers are staying careful, but they’re also tired, Abraham said.

“One thing the whole industry is suffering from is COVID fatigue,” he said.

Mohan is among those who are anxious, knowing the virus can still spread easily if people aren’t taking precautions.

“People are social animals,” Mohan said. “They’re going to meet. I worry the numbers are going to go up during the winter.”

Walsh said he’s especially concerned about family gatherings for the holidays and what it could mean for spreading the virus, particularly with asymptomatic carriers or students returning home.

“It’s becoming really scary again,” he said.