The New England Center for Children has a presence in 18 countries and is focusing on continued expansion to serve more children with autism.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Vincent Strully has soaring ambitions for his autism care center founded in 1975.

He wants the New England Center for Children to be for autism care and research as the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota is the sought-after place for general medicine, or the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston for oncology. With a presence in 18 countries, the New England Center for Children may be on its way, even if it doesn’t yet have the name recognition or reach of those other institutions.

In September, the center said it was opening a school in Lebanon, expanding its Middle Eastern operations already including long-running programs in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. A total of 7,000 students now use its software, called the Autism Curriculum Encyclopedia, which helps teach those with autism and for instructors to gauge their progress.

“The mission over the last 45 years has evolved consistently over time to develop solutions that could be scaled beyond just the students that the center serves,” said Strully, the Southborough center’s founder, president and CEO.

Expansion follows rising prevalence

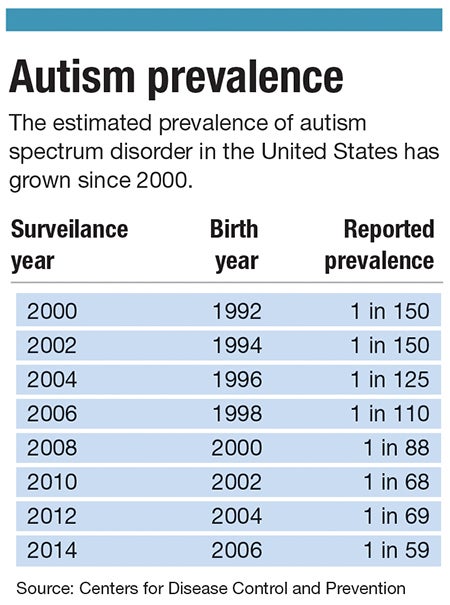

NECC's growth has followed an increasing prevalence of autism. In 2000, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention estimated 1 in 150 children to have autism. Now, it's 1 in 59.

There’s no consensus on exactly what causes autism, and no cure for it.

Research indicates genetics are involved in the vast majority of cases, and children born to older parents are at a higher risk for having autism, according to the national advocacy group Autism Speaks. Early intervention can help children develop the right learning, communication and social skills.

Wider prevalence has meant a growing need to help those with a disorder with social, communication or developmental challenges, or unusual interests or behaviors. For school districts, those unique obstacles can require more teachers in a classroom, and for those teachers to have specialized training.

NECC developed a teaching model for public schools, growing from one classroom to more than 63 across Mass., Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. The center was getting more referrals than it could accommodate, so it instead guided teachers for how to best help autistic students, said Amy Geckeler, its executive director of global consulting.

The center has incorporated education of its own workers into its mission. It has partnerships with Simmons University in Boston and Western New England University to provide on-site schooling for a master’s in education or applied behavior analysis or a doctorate in behavior analysis. Roughly 75 NECC workers earn such degrees each year.

Researchers at the center continue to work on better ways to support children with autism and their families.

In time, the center received requests from abroad to expand its services overseas. The first came in 1997 from the royal family of the United Arab Emirates, Strully said.

Today, NECC has nearly 300 employees working abroad, and the center says its workers account for more than half of all board-certified behavior analysts in the Persian Gulf region.

“This global demand began to find us as our reputation and success began to spread,” Strully said.

Where the center doesn’t have employees, it has schools using its software, which helps educators and behavior analysts best work with students and track their progress. Around 7,000 students are now being taught with the software, but the center expects that number to eventually rise to 40,000, Strully said.

Partnerships have been added in places like India and Kuwait, and a consultation program in Saudi Arabia. In September, the NECC opened a new school in Lebanon through a local partnership, which it says is the first such school in the country. The local school was founded by a couple who couldn’t find adequate care for their autistic son.

Local cultures are different in many of the countries where NECC operates, and careful consideration is made before beginning work in a new country. Strully visited the area around its planned facility in India for five days, for example, and the center considers U.S. Department of State safety guidelines.

Still, Strully said, advancements in autistic children's development has tended to change minds quickly if there were any differences in thought beforehand.

“Cultural barriers tend to fall away quickly if the kid is learning,” he said. “These are not insurmountable things.”

If Strully compares NECC to the Mayo Clinic or Dana-Farber, he says it doesn’t want to also be like Harvard University — too exclusive.

“We want to go where the kids are, and where the kids who need (the services) are,” he said.