As homelessness grows and as rental and home ownership costs rise beyond the means of more and more people, policymakers and housing advocates have pushed for a variety of solutions, one of which is inclusionary zoning.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

As homelessness grows and as rental and home ownership costs rise beyond the means of more and more people, policymakers and housing advocates have pushed for a variety of solutions, one of which is inclusionary zoning.

Leah Bradley, CEO at Worcester nonprofit Central Massachusetts Housing Alliance, Inc., is immersed in the challenge every day, dealing with the 600+ individuals completely homeless in the city and those others unable to afford a unit in the city.

“There are more and more folks who are employed who are having difficulty finding a unit … they can afford,” she said.

In seven out of the nine zip codes in Worcester, the median income is lower than what’s needed in order to afford a two-bedroom apartment, meaning half of the citizens can’t afford market rates,

“Those are also the zip codes that have a higher number of people of color, so we look at this as also a racial justice issue,” she said.

Those challenges are top-of-mind for city officials.

“The primary benefit of inclusionary zoning is to add another tool to help increase the affordable housing stock in Worcester,” said Peter Dunn, chief development officer for the City of Worcester. “Part of our strategic plan is to create opportunities for all, and this is a tangible example of implementing that strategy.”

However, Dunn did acknowledge the risk often cited with inclusionary zoning, namely it could dissuade some developers from investing in the community.

“We believe it’s the right time for such a policy,” he said.

And, such a policy needs to apply across the city, applying to all multi-family development with 12 or more units, he said.

“Through conversations we’ve had, developers seem to understand why we are making the recommendation at this time,” he said.

However, said Dunn, many market-rate housing projects still need assistance to make the economics work – tools like opportunity zones, various tax credit programs, and other forms of alternative financing are often still needed to make a project viable.

Fine-tuning inclusionary zoning

Critics of IZ have equated it with rent control, which is generally seen as reducing incentives to invest in housing.

“Personally, I don't think that IZ is quite the economists' bogeyman that rent control is, but the jury's still out on that one,” said Andrew Mikula, who is completing a master’s degree in urban planning at Harvard Graduate School of Design in Cambridge and research assistant at Boston public policy researcher Pioneer Institute.

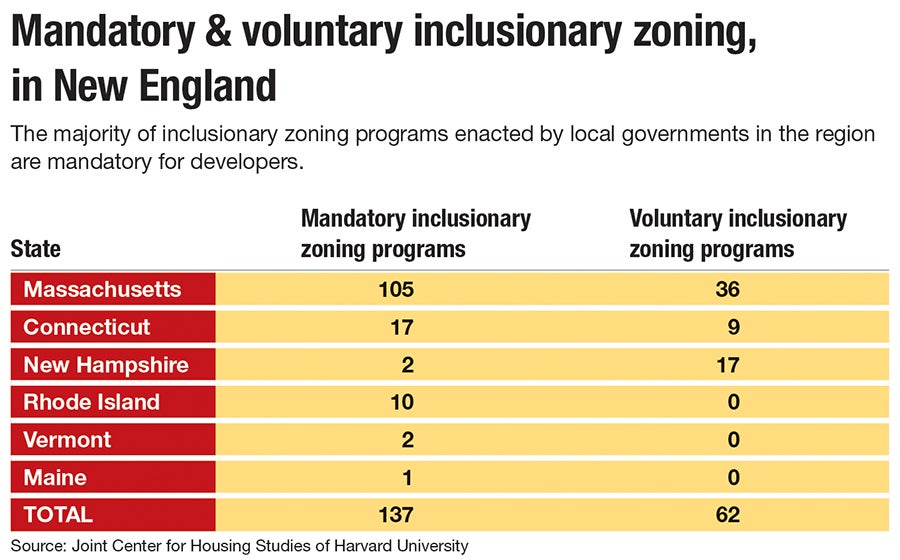

“It's more likely that IZ has some harmful effects when it's mandatory and ultimately restrictive, but IZ can also be voluntary,” said Mikula.

Some forms of IZ merely encourage developers to set aside units as affordable with density bonuses and other incentives they weren't able to take advantage of before. A good example, he said, is Massachusetts Chapter 40B, which adds flexibility to the housing market because it gives developers the ability to bypass local zoning codes, with the catch being they have to make their projects 20-25% affordable.

“There's a very active debate in the academic literature on the long-term supply effects of IZ,” Mikula said.

The theoretical long-term supply reductions suggested by IZ critics fail to materialize, Mikula said, but IZ does drive up the price of market-rate housing, presumably because developers pass along the costs of making affordable units to the other tenants.

“Also, unsurprisingly, IZ usually only produces a substantial number of affordable units if it is mandatory, as most density bonuses and other regulatory incentives don't negate the costs of affordable units for the developer,” he said.

Actually affordable

Taking his experience in helping a smaller town find ways to encourage affordable housing, Jeffrey Gordon, chairman of the Woodstock Planning & Zoning Commission in Connecticut, who hails from Worcester originally, makes a distinction between housing that is actually affordable and housing affordable according to a state formula.

Getting to actually affordable, through having more housing available, is an ideal, he said. And, like Mikula, Gordon believes if IZ is to help, it should include meaningful incentives for developers.

Providing more flexibility in how land can be used can help a developer be more creative in including affordable components but also ensuring sufficient profit to make a project worthwhile. And, Gordon said, maybe the market can be encouraged to deliver even more.

“If a developer decides to go beyond the amount of affordable housing they are required to do -- maybe, 50% or 100% more -- give them additional incentives that will encourage them to do that,” said Gordon. “Something like that could really work in a city like Worcester.”

For Bradley, of course, building more is critical, but she sees the idea of inclusionary – building communities that are inherently economically diverse – as in itself, an important goal.

“What we'd like to see is that folks who are working in our community can live in our community, too,” she said.