Major healthcare providers in Massachusetts and across the country have started taking steps to rectify racial discrepancies in healthcare services and outcomes.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When John McDonough was doing his graduate studies, he was taught there were three pillars of U.S. healthcare policy: cost, quality, and access. Everything else, he said, could be compartmentalized under one of the three.

After the Affordable Care Act, however, McDonough said he observed a fourth pillar start to emerge: population health.

And two years ago, after the COVID-19 pandemic started, he realized there was a fifth: health equity, which he used to think could go under cost, quality, and access.

For the first time, major healthcare providers in Massachusetts and across the country have started taking steps to rectify racial discrepancies in healthcare services and outcomes.

Before COVID, it was rare to see the word “racism” inside a medical journal, McDonough said.

But today, it seems that the U.S. healthcare industry is starting to wake up and directly address problems, like high C-section rates for pregnant Black mothers.

“I taught a program two months ago and I said, ‘Raise your hand if your institution is doing something new on health equity.’ Every hand in the room went up,” he said. “Whether it's real or for show, it’s a different moment.”

Healthcare leaders throughout the region came together to discuss equity, population health, and the latest news at the Worcester Business Journal’s annual Central Massachusetts Health Care Forum, held virtually Oct. 27. McDonough, a professor at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, was the event’s keynote speaker.

Keeping the focus on health equity

The panel of experts said strides are being made throughout the healthcare industry to provide care across ethnic and racial lines.

Worcester-based insurer Fallon Health is working toward accreditation in health equity from the National Committee for Quality Assurance, said Matthew Herndon, the company’s senior vice president, chief state programs officer.

But with progress on the equity front has come backlash, McDonough said. Healthcare equity has become a political topic, in line with the national discussion surrounding critical race theory.

“It’s kind of a form of Trumpism,” he said.

On the other hand, some community health centers are wondering what took other providers so long.

“I’m totally on board with the push for health equity, because we’ve been doing it as community health centers for more than 50 years. We’re just thrilled that the healthcare delivery system overall is finally realizing the importance of it,” said Stephen Kerrigan, president and CEO of the Edward M. Kennedy Community Health Center in Worcester.

Kristin Mattocks, associate dean for veterans affairs and professor of population and health sciences at UMass Chan Medical School in Worcester, works as a women's health researcher with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

She sees firsthand how health equity plays into people’s lives.

“I just spoke to a woman yesterday from North Carolina who’s going to be doing our doula study, and she literally was crying on the phone when I was enrolling her into the study because she said her last birth was so bad, nobody listened to what her preferences were during labor and delivery. She was sort of roughly handled,” Mattocks said. “She was just so overcome with emotion at the ability to have somebody support her during the labor and delivery process.”

The highest spending for the worst outcomes

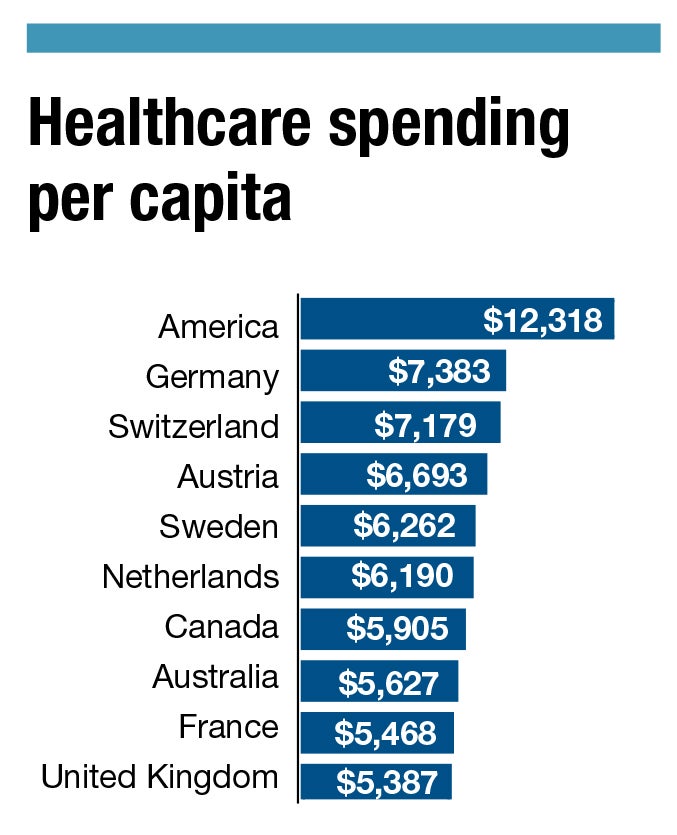

Americans pay a lot more for doctors office visits, surgeries, and other medical services compared to other wealthy nations.

U.S. healthcare spending per capita is $12,318, more than twice the worldwide average of $5,829 and 64% higher than the country that holds the number two spot, Germany, according to McDonough’s keynote presentation.

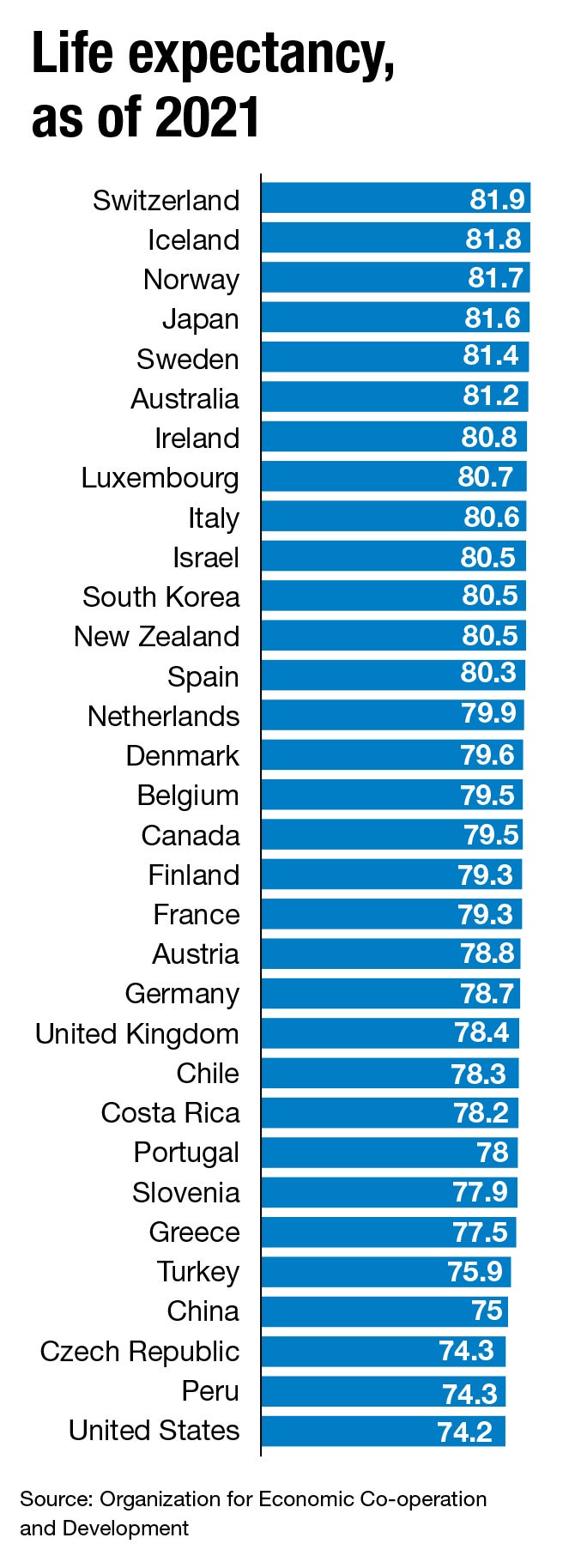

The high cost of health care in the U.S. wouldn’t necessarily be a terrible thing on its own, McDonough said, but health outcomes in the U.S., like life expectancy, are well below what they are in other wealthy nations.

“There’s nothing wrong with spending this amount of money if in return for it we could brag that we have the best health care outcomes, and systems and quality in the world; and unfortunately, that’s not what we have,” McDonough said.

U.S. life expectancy, which started a steady increase in 1980, plateaued starting around 2010 and took a nosedive when COVID-19 hit, McDonough said.

The nation had around 20,000 drug-related deaths in 1999, a figure that had jumped to 96,096 by 2020. Diagnoses of diseases like obesity and diabetes have risen significantly since the mid-1990s.

Even though healthcare costs in the U.S. are high, there is some good news, McDonough said. Because of the Affordable Care Act – specifically, provisions that went into place in 2014 – about 8% of the U.S. population was without health care in the first quarter of 2022, down from 14.9% in 2000. Most of the insured population has private coverage, he said.

New federal legislation in the last two years like the American Rescue Plan Act and the Inflation Reduction Act include provisions for healthcare cost control.

The IRA puts the federal government in the business of controlling prescription drug prices for the first time. ARPA cuts down the percentage of household income federal health insurance holders have to pay toward their premiums and extends coverage to people within 400-600% of the federal poverty level.

“That’s a big deal in terms of the affordability and stability of the Affordable Care Act that people had been trying to advance for about 10 years,” he said.