The Affordable Care Act survived the Trump Administration. Now the vice president who helped get the act passed in 2010 is growing it to provide coverage of more Americans.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The Affordable Care Act survived the Trump Administration. Now the vice president who helped get the act passed in 2010 is growing it to provide coverage of more Americans.

President Joe Biden is already off to a good start in expanding some elements of the program – one of his top campaign goals.

Biden’s upgrades to the ACA highlight a year or more of proposed federal and state legislative measures, changing the way health care is provided for and delivered. On the state level, new laws are being contemplated for aid in dying, telehealth, behavioral health, and vaccine mandates.

A $1.9-trillion pandemic relief bill, the American Rescue Plan, included lowered monthly payments for a broader segment of families and new incentives for states that haven’t expanded Medicaid already – namely Florida and Texas – to do so now without as many additional costs.

Those expansions were put in place only through 2022, leaving its longer-term shape more open-ended. But it nonetheless makes important strides toward making the ACA more affordable in two important ways, said Megan Cole, a Boston University School of Public Health professor.

First, the expansion will help middle-class families find affordable coverage by removing an income cap on premium subsidies, with anyone enrolling paying no more than 8.5% of their income, she said. It’ll give more generous subsidies to lower-income families who qualify for plans with no premiums, and for a broader segment of households to purchase better-quality plans with smaller deductibles.

Those expansions are estimated to insure 1.3 million people for the first time at a cost of $34 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

The ACA, more than a decade after its passage, already made a significant dent in the number of Americans without health insurance. From more than 15% who were uninsured then, the rate is now 9% as of 2019, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Massachusetts leads the nation in health coverage, with only 3% of the population uninsured, according to Kaiser. That can mask how much of the rest of the country remains uncovered: 9.2% nationally and far more in some of the nation’s most populous states, including 18.4% in Texas and 13.1% in Florida.

“We’ll have to see how many [states] take advantage,” Cole said.

A report in January by the nonprofit Urban Institute in Washington, D.C. explained in part why: an estimated 47% of uninsured adults said in a survey they hadn’t looked for information on potential coverage or tried obtaining it. Most of those who didn’t try didn’t think they’d qualify, the report said.

Obamacare survives a major challenge

Experts on federal health policy portrayed the ACA as having made it through Donald Trump’s four years as U.S. president despite his efforts to first overturn it through both legislative and judicial efforts, and later by weakening it by ending marketing efforts and assistance grants.

“It’s clear that essentially from every angle they could, the Trump Administration was trying to take apart the ACA,” said Paul Shafer, a Boston University School of Public Health professor.

“There was no appetite to go back and fix things that weren’t working as well,” said Amy Lischko, a professor at the Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston. Instead, she said, Trump and Republicans attempted to repeal the plan or have it deemed unconstitutional without efforts to strengthen it.

Cole said she sees other areas where important improvements could still be made to the ACA, including extending the period of time for women to receive Medicaid coverage postpartum, which now ends after 60 days. Shafer also believes that period should be lengthened.

“Complications can lead to increased risk of death for up to year after delivery,” he said, “so this was a long overdue step to address the concerning trends in maternal mortality, which disproportionately affects Black and Indigenous women in our country.”

Though the ACA is at least in a temporary expansion, experts don’t expect larger-scale changes to follow. Democrats control both the House and Senate in Congress, but not by a wide enough margin for a required two-thirds majority in the Senate.

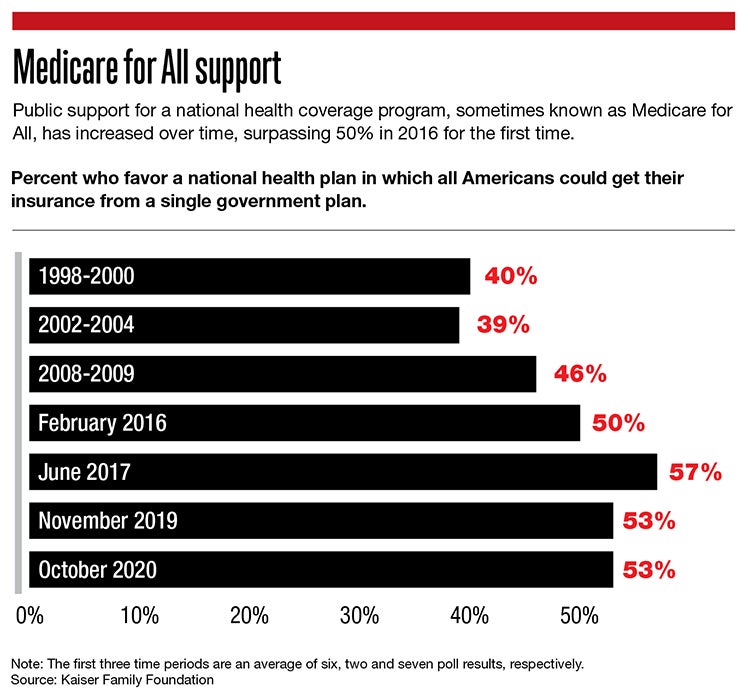

That could preclude potential changes, such as Biden’s campaign goal of having 97% of Americans covered, or Medicare for All, which would put everyone on public insurance plans in a single federal system, or lowering the age of those who qualify for Medicare.

“The 97% figure is a realistic goal but a lot of things have to happen to get there,” Cole said.

Experts don’t envision another change first championed by Trump: a significant lowering of prescription drug prices. Trump wasn’t also given any type of substantial credit for having accomplished his own drug-price goal.

“There wasn’t much in a big way done to lower drug prices,” Lischko said.

Nor does she think Biden is likely to be able to do the same. With drugmakers seen as heroes of sorts for developing COVID-19 vaccines so quickly, she said, the pharmaceutical industry isn’t likely to be seen as a villain of sorts as its been in the past, an easy target for the White House or Congress to go after with a sure bet that the move would be widely popular.

End-of-life options for terminally ill

Health policy changes could also be on the horizon with Massachusetts state legislation on Beacon Hill.

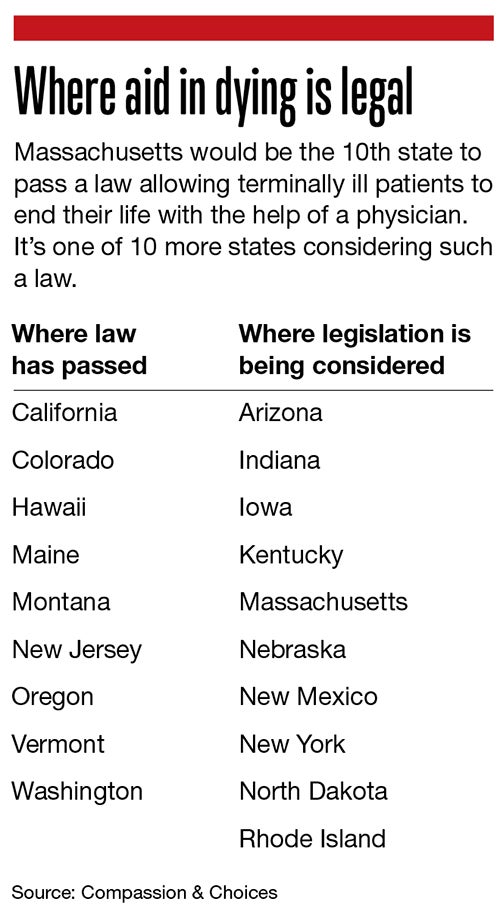

One bill would make Massachusetts the 10th state to allow terminally ill patients to end their lives with the help of a physician.

The bill, which has been filed before but never made it to a full legislative vote, would put strict measures in place – a patient needs to be at least 18, for example, and given a life expectancy of six months or less. At least one consultation by a licensed mental health professional is mandatory to ensure the patient is capable of making the choice of ending their life, and two witnesses must verify the request – and one can’t be a relative or someone who’d be entitled to any portion of the person’s estate.

Advanced age alone isn’t enough to make someone eligible for the aid-in-dying program, which has also been called “death with dignity” or the less euphemestic term “assisted suicide.”

One of the bill’s co-sponsors is Rep. James O’Day, a Worcester Democrat, who said safeguards are in place to ensure a patient’s choice to end their life is what they truly wish, something he called a compassionate option for the terminally ill.

“These have been going on for the last two decades,” O’Day said of similar laws in place elsewhere, the first of which passed in Oregon in 1997.

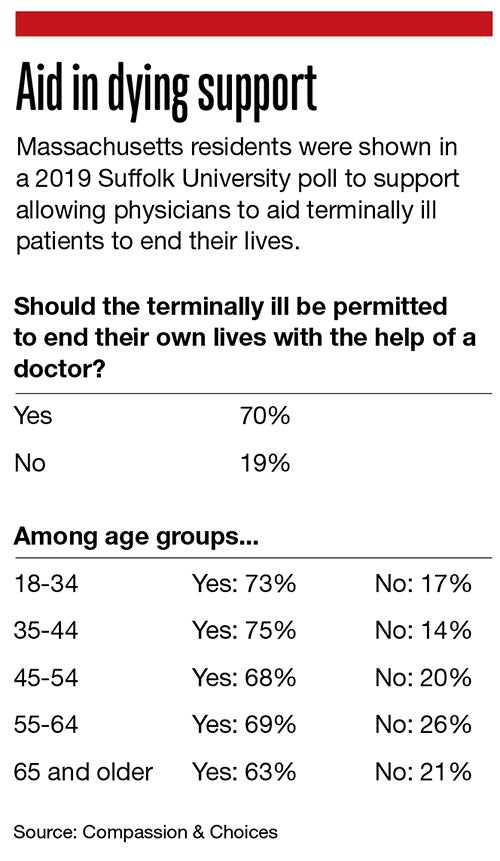

An aid-in-dying program appears to have the support of the Massachusetts public.

A November 2019 poll by Suffolk University and The Boston Globe found 70% in favor of allowing physicians to help the terminally ill end their lives, compared to 19% against (others were undecided or didn’t answer). Exactly three out of four said they’d want doctors to stop treating them if they had an incurable condition and were in terrible pain, and 66% would do so if they were in a condition in which they were entirely reliant on others.

That could indicate public opinion has shifted since an aid-in-dying bill failed at the ballot in 2012 by 2 percentage points.

There may be less formal opposition this time, too. The Massachusetts Medical Society used to oppose it, but chose to be neutral in 2017 and remains so. The Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association doesn’t have a formal stance.

An opposition group, called Second Thoughts Massachusetts, organized in 2012 to defeat the statewide ballot question and remains opposed to a proposed policy it says discriminates against the disabled – what it calls a “better dead than disabled” mindset, a feeling of shame of having to rely on others. The group has warned against potential elder abuse, misdiagnosis or health insurers who might push for pre-emptive end-of-life choices to save on their medical care costs.

Telehealth, vaccines and more

State legislators are considering a range of other health-related bills this session, including one aiming to close technological gaps for patients using telehealth and another to encourage vaccine immunization by removing any opt-outs other than religious or medical exemptions.

Among other initiatives, the industry group Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association is advocating for bills to extend a community hospital trust fund that’s due to expire, and a behavioral health bill to address staffing shortages and delays in providers obtaining needed licenses.

Telehealth, or online appointments with health providers, have been a valuable asset for patients to receive services during the pandemic, said Dr. David Rosman, the president of the Massachusetts Medical Society, a group of physicians and those in medical school or training. It has enabled patients who were least likely to access medical care, notably people of color, to catch more appointments because they no longer have to get to a doctor’s office in person, he said.

Still, telehealth has left some major gaps, with adaptation still in early enough phases that changes should be implemented, Rosman said. They include aid for those without reliable internet connections and those without the technological know-how to sign on to talk with their doctor.

“We can sometimes forget that advancements often worsen inequities if we don’t fight to make sure it doesn’t,” Rosman said.

A bill filed in February proposes two pilot programs: one supporting services in some communities, including the purchase of internet-connected devices, to help more patients access telehealth, and another putting in place a technological literacy program for older patients or those with limited English abilities. It would also waive insurance co-pays for telehealth visits, something widely put in place during the pandemic on at least a temporary basis and add reimbursement for interpreter services, which pre-pandemic were typically given in-person.

The vaccination bill, filed in February, aims at getting more of the public vaccinated, particularly children. It would require any school, college or child care center to enroll students or participants only if they’ve proven they’ve been immunized.

Any program that doesn’t show a high enough compliance rate to have herd immunity would be included in an online list of what it calls elevated-risk programs.