To move on from the garage to the real world isn’t as easy as “I have an idea!” In the world, we cherish ideas and people who bring them to life, but what is often lost is to make something, to start a company, to build something new, money is required.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The story usually starts in a garage. There’s a man – almost always a man – sitting behind a computer with the garage door lifted open. He’s working frantically. A camera would pan slowly in front of it as time lapses. From sunup to sundown, he works bringing an idea to life. Long hours.

These are the origin stories we’ve been told of Silicon Valley and its entrepreneurs. The story of Microsoft Corp. and Apple Inc. It’s Google and Alphabet Inc. For Facebook – well, Meta Platforms Inc. now – the garage myth was swapped out for a dorm room. We’ve been told these stories countless times. Amazon.com, Inc. was a warehouse for books and then became AMAZON. Now Jeff Bezos is one of the richest people in the world. Steve Jobs and his turtleneck were one of those too when he was alive. Bill Gates still hits near the top of the list. But those stories are myths. Legends. They pulled themselves up and made their dreams a reality. But, the garage – if it even existed – was the beginning, and it wasn’t as simple as dreaming.

To move on from the garage to the real world isn’t as easy as “I have an idea!” In the world, we cherish ideas and people who bring them to life, but what is often lost is to make something, to start a company, to build something new, money is required. Capital. Investment. And there are a few ways to go about it.

For Aaron Birt and the team at Solvus Global in Worcester and Leominster, when they started their company, the goal was to solve problems. They wanted to incubate ideas. Birt and co-founders Sean Kelly were graduate students at Worcester Polytechnic Institute and saw an opportunity to start a company not focusing on one thing, but searching out specific dilemmas in markets like scrap metal recycling and additive manufacturing, with the idea of incubating ideas to become answers and eventually stand-alone companies.

Solvus bridges the gap between an incubator and a venture studio. A venture studio rolls out multiple companies in quick succession so they can build out an idea and reinvest capital. Incubators have been around for a long time and usually they’re places where entrepreneurs can get office space, management training, and other services in the hopes of getting venture capital.

Solvus hasn’t taken any venture capital funding because its model is a bit different. Birt and Kelly don’t want to send a specific idea into the world and hope someone ponies up money for the research. Instead, they want to build a company and spin it off into its own entity ready to make a product. They keep equity in the spinoff. They provide the tools, the people, and the training for the new company, and when the product is ready to stand alone, they send it out into the world. To do all of this, Kelly and Birt had to raise their own capital. That took some ingenuity and patience.

Kelly and Birt looked for loans from friends and family. They scoured for money they could acquire via government programs. They eventually went to banks to take out loans. They tested the patience of their partners, burned through savings, and maxed out credit cards. They even sold Bitcoin. They found a way to sell their time and expertise to raise money to start Solvus.

“After a year or so, we were able to sort of have those consistent consulting projects,” Birt said. “We started winning some government programs for a combination of ideas we had, as well as technology that we had developed while in grad school.”

State support for startups

One of the programs where Solvus was able to find funding came in the form of a $1.6-million grant from the Massachusetts Technology Collaborative, which is a state-funded economic development agency headquartered in Westborough. Solvus received a Massachusetts Manufacturing Innovation Initiative grant, which supports later-stage startups with commercialization through capital investments. In Central Massachusetts, companies like LEAP R&D Corp. at WPI and FLEXCon Co., Inc. in Spencer have received the grants.

“From there we kept rolling it, so we kept reinvesting everything we had back in the organization. There was no money paying us back for not taking a salary for all of those years, all of that kept being reinvested,” Birt said.

“That is how you start something from zero with very little,” Birt continued. “Time is the one thing that is really valuable to other people, but you can do it for free and then you build off of it until you find your right niche to be able to continue driving your funding.”

MassTech has specific grants designed for each cycle of the development process for startups, which is important because venture capital companies like to see early stage funding, said Christine Nolan, director of the Center for Advanced Manufacturing at MassTech.

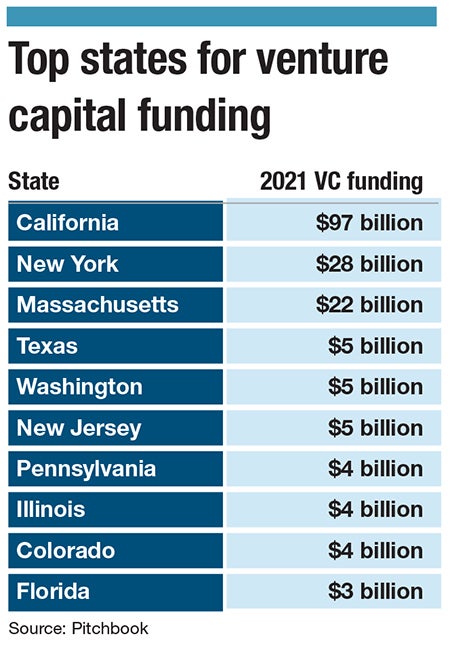

At $22 billion in 2021, Massachusetts has positioned itself as a state where VC money flows, receiving the third most VC money in the country, behind California and New York, according to Seattle business capital database Pitchbook.

Building off Cambridge’s success

The next step for Central Massachusetts is harnessing all the money that’s out there and bringing it to the region.

A specific area where this can be achieved is in the biotech sector, said Jon Weaver, president and CEO of the Massachusetts Biomedical Initiatives incubator in Worcester. In 2022, more than $8.7 billion was in venture capital money flowed to biopharma companies in Massachusetts, one year after startups in the commonwealth got $13 billion, according to the industry group Massachusetts Biotechnology Council.

For startups to get to that point where they get funding, though, they have to take years perfecting their product and a few more years to get approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Weaver said it’s usually 10 years and $1 billion spent on research before there’s a return on investment.

At the same time, the investment can be worth it, and Weaver sees money beginning to flow into Worcester’s burgeoning biotech sector. Cambridge is still the commonwealth’s life sciences hub, with nearly 50% of VC money flowing to its biotech companies, but it used to be not all that different from Worcester, he said.

“If you walked through Cambridge not that long ago, it was a bunch of empty parking lots and brown brick buildings with a bunch of potential,” Weaver said. “And because of the combination of education and medical companies and the workforce and all these other pieces that are built into our cluster, it has erupted and taken off as a worldwide example of biotech.

“And Worcester has a lot of the same ingredients, and as that cluster [in Cambridge] begins to spill out to the point where it can't be fully self-contained within l-95,” he said. “Worcester has an awesome value proposition to capture that.”

When it comes to funding, though, don’t believe all of the origin stories. There is money flowing, of course. Investors are making bets, and entrepreneurs are trying to prove they’re the best one. The most important funding still comes early on from friends and family, much like Gates got from his father, a lawyer with a huge practice. Bezos’ ex-wife and the person who helped him start Amazon, MacKenzie Scott, worked for author Toni Morrison and the multinational hedge fund D. E. Shaw & Co. before Amazon took off.

“Don't believe everything that is in the news with a lot of the folks that say they start from nothing,” Birt said. “Because a lot of times, they have very extensive networks of wealthy friends and family.”