Banking and finance leaders at Central Massachusetts institutions see education as a key way to help combat financial illiteracy.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Clinton Savings Bank begins offering financial education services for children as young as kindergarten.

Starting at such a young age is key, as it is one of the most effective ways to combat the growing problem of financial illiteracy in adulthood, said Ellen McGovern, senior vice president and chief marketing officer at Clinton Savings Bank.

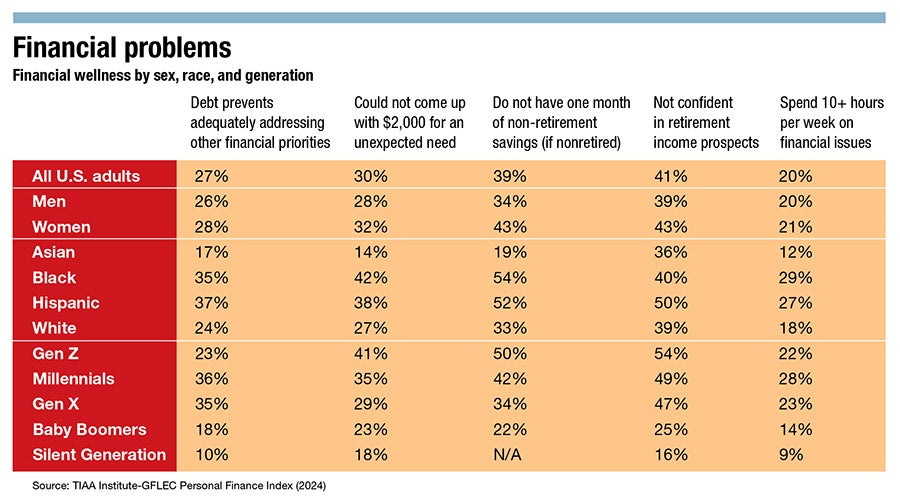

A 2024 study conducted by the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center, a California-based research agency, found 57% of U.S. adults are financially literate while 30% couldn’t come up with $2,000 to cover an unexpected need.

Banking and finance leaders at Central Massachusetts institutions see education as a key way to help combat financial illiteracy. For example, last year Cornerstone Bank increased the number of financial literacy programs it held from 114 to 204, with 52 employees collectively spending 568 hours on educational programming, according to its annual report.

“People in this country are asking for help with finances. So there is a need for this, and we know that it works when people get it. The challenge is that not everybody is able to access financial education,” said Lindsay Torrico, executive director of the ABA Foundation, a nonprofit from the American Bankers Association providing banks with free programs and resources to promote the financial wellbeing of their customers and communities.

Financial literacy in schools

In the U.S., 26 states require financial coursework to graduate high school, according to the National Endowment for Financial Education. Massachusetts is not one of them.

At 18 years old, teens are flooded with credit card offers they often don’t know how to navigate, said McGovern. She sees teens accepting one or more credit cards at a time and quickly unable to meet their minimum payments because they don’t understand how interest rates work.

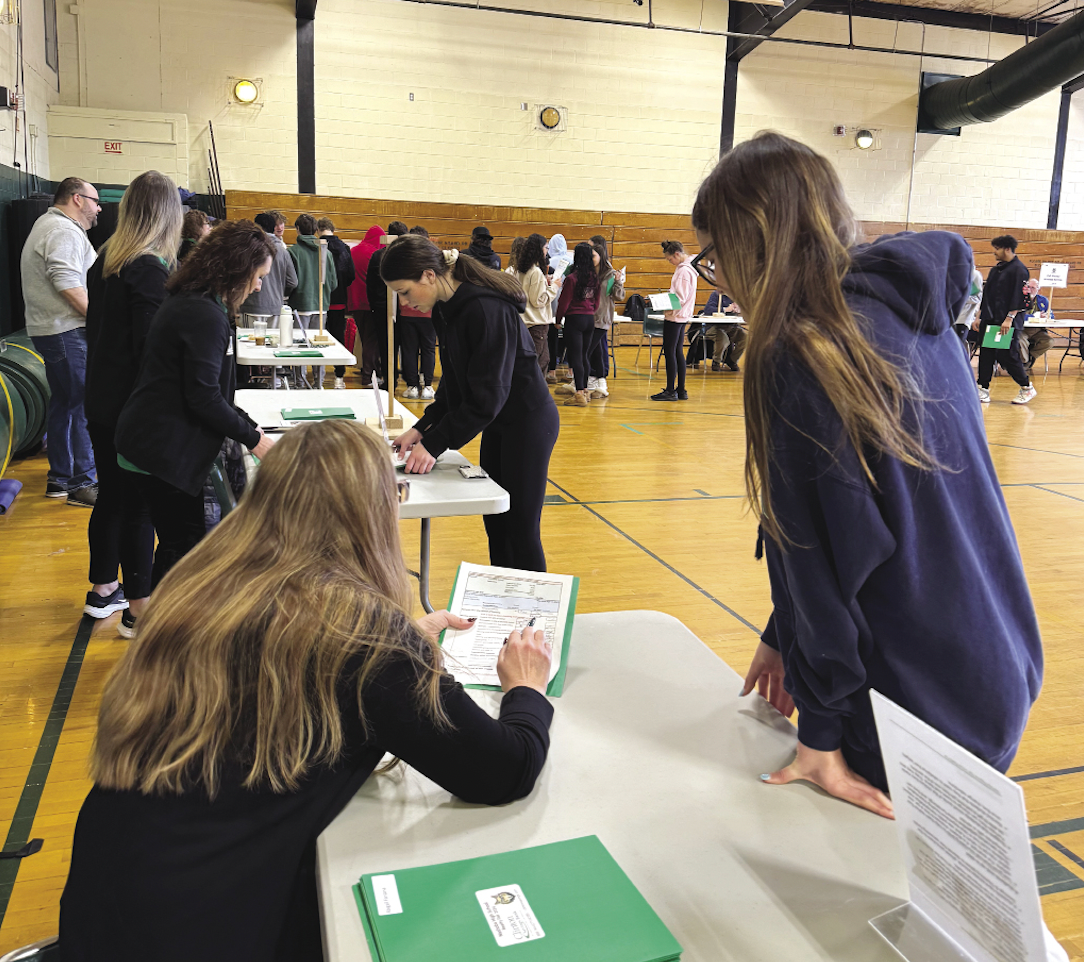

Since many Central Massachusetts schools aren’t able to provide financial courses due to budget constraints, Clinton Savings Bank offers programming around its market, said McGovern.

Those services from Clinton Savings Bank include in-school banking days, seminars, and online courses. The bank has two full-service branches run by students at Tahanto Regional Middle/High School in Boylston and Nashoba Regional High School in Bolton. Overseen by a Clinton Savings Bank relationship manager, the in-school branches afford students the opportunity to learn how to become a bank teller and service their peers and teachers.

Selected as an elective, more than 70% of the class’ curriculum is based on financial literacy covering checking and savings accounts, balancing checkbooks, credit cards, and even auto loans, McGovern said.

Financial first steps

Financial literacy is a necessary piece of the puzzle, but it’s certainly not the main objective for Terra Oliveira, director of financial empowerment at Worcester Community Action Council, a nonprofit working to bolster economic self-sufficiency.

“Financial literacy is the base level of financial empowerment,” said Oliveira. “Financial literacy is required if I'm going to be achieving my financial and life goals. But it's step one, and we wanted to do so much more here.”

Financial literacy is understanding the rules of the game while empowerment is about recognizing that money is a resource to achieve one’s goals in life as opposed to money being the goal, she said.

In an effort to boost financial literacy and health, the ABA Foundation launched a five-year goal in 2023 to help 5 million people across the country achieve financial stability by 2026.

“Financial literacy on its own is not going to solve the economic challenges that people are dealing with, but it is a necessary part of a comprehensive response, a comprehensive approach to address these needs,” said Torrico.

More than 70% of the country is not financially healthy, according to a September study released by the Financial Health Network, a Chicago-based financial resource nonprofit, which defines financial health by eight indicators, including spending compared to income, amount of liquid savings, and status of manageable debt.

Because not every child is afforded financial education through schooling, or any at all, the ABA Foundation offers banks its Get Smart About Credit program, a national campaign providing free financial education to high school students and young adults through local banks.

“If we can preempt some of the financial regrets that a lot of people have and start early and educate them on what they need to know … We're going to set them on the right path both for them and for their future families,” said Torrico.

Barriers to banking

While financial workshops at a traditional bank may be beneficial to some, a large demographic can be left behind within those services, said Oliveira.

As a financial coach at WCAC, Oliveira prioritizes removing the shoulds of finances and instead focuses on a holistic approach to addressing the needs of those living with medium to low incomes. She works one-on-one with clients, as opposed to a workshop setting more commonly seen at banking institutions.

“When we are talking about money with clients, we're often talking about much more than you would ever disclose at a bank. We're talking about your family dynamics. We're talking about your childhood and what lessons you learned from your parents,” she said.

Oliveira, who herself was once denied an account at a bank where she attended a workshop, said being denied access to a bank can lead to a prolonged continuation of being underbanked.

“The average person, when they are told no once, believes that they will be told no again,” she said. “There's a lot of assumptions about people who end up in my seat, that they're spending money like they shouldn't be and by and large, that's not the case. It's just that they're trying to live within their means and it's very tight.”

As of the end of last year, 6% of Americans were unbanked, a term meaning neither they nor their spouse or partner had a checking, savings, or money market account, according to the Federal Reserve. That rate jumps to 23% when focusing on those making $25,000 a year or less.

Unbanked percentages were highest among young adults with 11% of individuals 18−29 reportedly unbanked. Percentages varied greatly depending on race and disability status as 14% of Black adults and 11% of Hispanic adults were unbanked as opposed to 4% of white and Asian individuals; 11% of those with disabilities were unbanked as opposed to 5% with no disability.

People aren’t always comfortable asking why they were denied access to a bank, Oliveira said. She works to connect her clients with banks with relationships with WCAC, as those banks have agreed to override their internal systems and allow for anyone to utilize credit-building products and open a bank account.

Sitting down with her clients for the first time, Oliveira’s initial move is to get a clear picture of what their finances are, determine their readiness for their larger goals, and identify small first steps toward those objectives. Oftentimes, those first steps don’t look like what her clients were expecting, like when she advises clients that correcting an item in collections is actually a step towards homeownership. Reframing what fiscal decisions are opening future doors is a key part of Oliveira’s work.

“I want my clients to feel that no matter what their paycheck is, that every week and every month they're making progress. They're building the life that they want even if that pace is slow and steady,” said Oliveira.

And that, she said, is empowering.

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.