On the last Thursday in October, the behavioral health department at UMass Memorial Health – Harrington, in Webster, officially marked the opening of a new and expanded adult psychiatric unit at its campus on Thompson Road.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

On the last Thursday in October, the behavioral health department at UMass Memorial Health - Harrington, in Webster, officially marked the opening of a new and expanded adult psychiatric unit at its campus on Thompson Road.

The unit replaced a 14-bed unit previously operated in Southbridge, and added 10 new beds to the department’s operations. Located adjacent to a pre-existing co-occurring disorder unit, the new psychiatric space brings the Webster hospital’s total capacity to 40 beds – an increase of 33%.

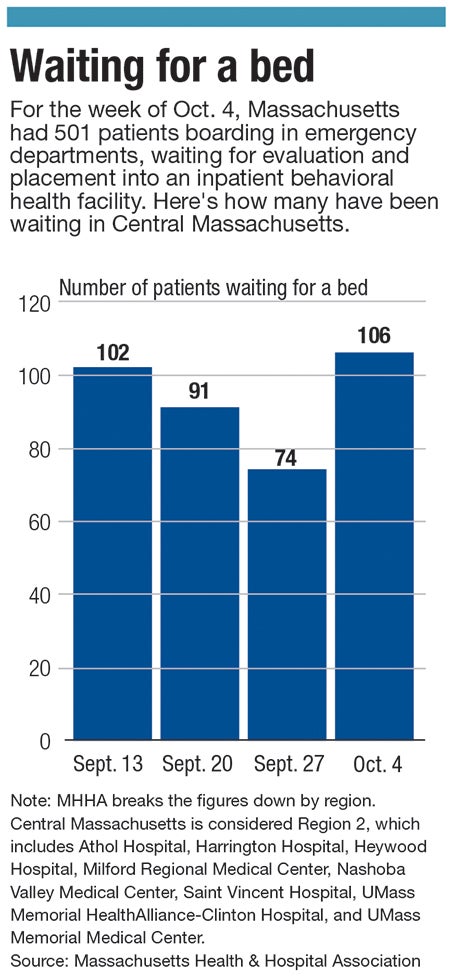

The expansion will not only increase the number of psychiatric patients the hospital is able to take on at one time, but is part of a larger statewide effort to curtail waitlines for inpatient psychiatric care, which are plaguing healthcare systems across Massachusetts.

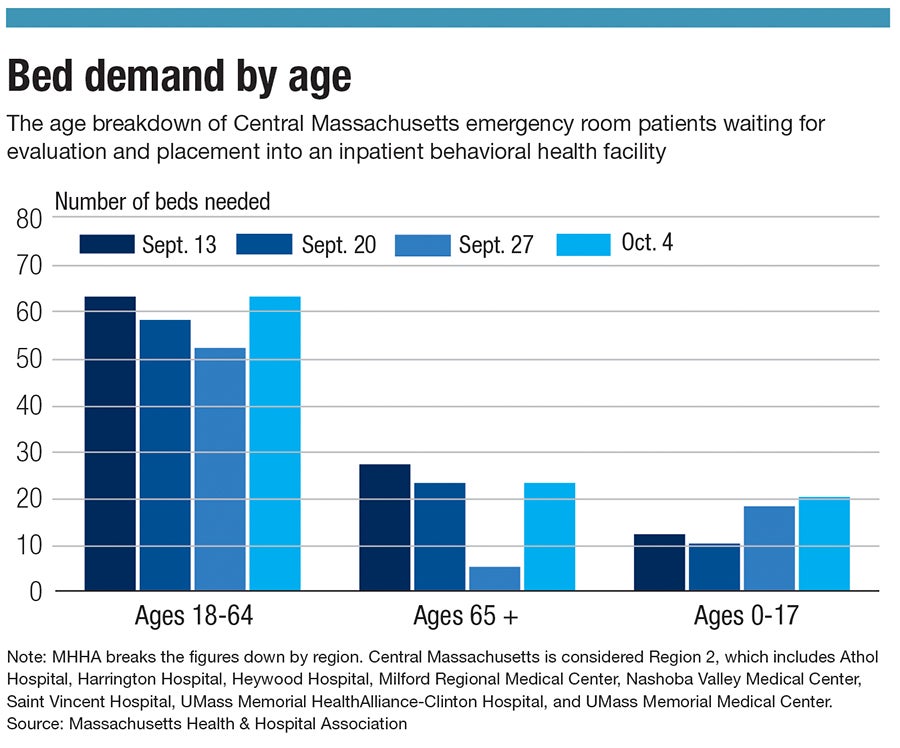

“The waiting period and the number of boarders in the emergency room is, I think, greater than I've ever seen before, and with kids in particular … There’s a significant lack of resources when it comes to inpatient setting,” said Greg Mirhej, vice president of behavioral health at Harrington.

These waitlines are so prevalent that, according to the Massachusetts Senate, emergency department boarding – which happens while patients spend an extended period of time waiting to be admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit – has increased 400% since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

But while the need for psychiatric care seems to have increased over the last year and a half, Mirhej said the need for more beds is only one piece of the puzzle. Opening the new Webster unit immediately reduced the number of boarding emergency department patients in the UMass-Harrington system, but behavioral health care is still grappling with staffing shortages and a need for comprehensive mental health care support to reduce the number of patients who require inpatient care.

More than numbers

Although more psychiatric beds are certainly needed in Massachusetts, Mirhej is quick to underscore it’s more than just a straightforward numbers problem. Even adding hundreds of beds, he said, would likely not be a complete resolution. Healthcare workers need to tend to the patients using those beds, and not every inpatient would necessarily need inpatient-level care if other services were more readily available – and funded.

Like many other sectors, health care has suffered from staffing challenges, and these challenges have had an impact on the behavioral health sector, said Mirhej, including the number of psychiatric beds a healthcare system is able to keep online.

“Staffing, in general, has been really really hard. If you talk to any of the hospitals, that’s certainly their No. 1 problem,” he said.

Recruiting and retaining social workers, therapists, and other mental health professionals has been a challenge everywhere, including at UMass-Harrington. A social worker himself, Mirhej understands the difficulties of the job.

“Behavioral health, it’s a challenging area to work in,” he said.

And at the same time, he said, psychiatric and substance use disorders don’t exist in a vacuum. There’s often other issues at play with patients, including employment, health, and nutrition problems. Failing to deal with those areas leads to readmissions and relapses, Mirhej said. What can help prevent re-exacerbation of mental health problems, as well as prevent inpatient stays in certain situations, is improving outreach efforts for discharged patients, as well as opportunities for comprehensive support.

One such pilot program Harrington previously participated in, he said, stationed social workers in the emergency room to intervene in mental health-related situations, nearly halving the number of adult psychiatric patients waiting for care in the emergency room. But then, funding for the program ran out.

Harrington is participating in another similar effort, a mobile respite clinic run by Worcester nonprofit Open Sky Community Service. It’s so popular, he said, there is a waiting list.

Through the program, which is backed by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, professionals from the nonprofit reach out to those having behavioral crises in the emergency department, or in inpatient units, to provide support to help them return to their homes. This support can come in different forms, including helping them access housing, apply for emergency food stamps, and accessing their future outpatient appointments. Since March, 84% of the clients Open Sky served through this program did not return to the emergency department.

“Part of our model is we were available to rapidly respond to their needs,” said Jillian Ricard, director of respite services at Open Sky.

The program’s funding is set to last another two years.

Ed Moore, president and CEO of Harrington Hospital, is particularly proud of what the network has been able to provide the region in terms of psychiatric help, particularly when it comes to covering almost the entire continuum of care. Aside from its psychiatric unit, for example, the Webster campus opened last year addiction immediate care – essentially an urgent care center for those with substance use problems. Moore put the onus on other healthcare networks to commit to doing the same.

“I like to think of it as a model for what community hospitals can do and should do,” Moore said.

Legislative action

On Nov. 17, the Massachusetts Senate passed a bill aimed in part at tackling the pervasiveness of emergency room boarding, sending it on to the House. An omnibus bill dubbed the Mental Health ABC Act 2.0: Addressing Barriers to Care, it would set aside $400 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds to bolster the state’s behavioral health sector in a variety of ways. Some $122 million would be used to recruit and retain 2,000 behavioral professionals.

Among the many proposals in the bill is a series of initiatives specifically targeting the emergency department boarding crisis.

Those include creating an online portal to help healthcare providers search for and find open beds, and requiring all emergency departments to have a behavioral health clinician always on-hand to evaluate and stabilize admitted patients who have behavioral health issues.

Additionally, the bill would mandate coverage and eliminate prior authorization for mental health acute treatment and stabilization services, effectively reducing the power insurance companies have to control what kind of treatment a patient receives, especially in emergencies. At the same time, it would require insurance companies, including MassHealth, to follow a uniform set of criteria from the American Society of Addiction Medicine for making decisions related to substance use disorder treatments.

Although the bill is new, Gov. Charlie Baker expressed support for using the state’s legislature to bolster the behavioral healthcare sector, particularly in the face of the pandemic. In general, over the last year, his administration has called for improving access to psychiatric care.

“Out of the darkest days of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is reason for hope, because we are no longer talking about the need for quality mental and behavioral health care in whispers, shamed by stigma,” Senate President Karen Spilka (D-Ashland) said in a statement announcing the bill. “As we all face the emotional difficulties and social isolation of the pandemic, people across our commonwealth are talking about their struggles with mental health, and the call for quality mental health care is now a roar.”

When it comes to the question of whether government intervention can make a difference in this area, the proof is in the work being done in Webster. It was with state financial help that UMass-Harrington built out its expanded adult psychiatric ward, in the first place, using a $1.2-million grant to partially fund the project.

“Truthfully, I have to say that I think that the state has been really listening in many ways to a lot of what’s going on,” Mirhej said.