The City of Worcester’s team-friendly effort to pay off the $160-million cost of the Polar Park baseball stadium over 30 years is off to a rocky start.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The City of Worcester’s effort to pay off the $160-million cost of the Polar Park baseball stadium over 30 years is off to a rocky start.

Yet, despite a revenue shortfall in the Worcester Red Sox’s first season at the ballpark, city officials so far avoided breaking the promise they made in 2018 when the team announced it was moving from Rhode Island to the Canal District : The stadium will pay for itself.

“With a project of this size, you are constantly course correcting,” City Manager Edward Augustus said. “You just have to keep your eye on the ball, which is getting the project functional.”

The 30-year plan to pay off the city’s long-term borrowing is reflective of the rushed nature of the entire ballpark project, where officials are solving problems on the fly and figuring out how to meet their significant team-friendly obligations with minimal time to prepare. To date, the city doesn’t have a separate and transparent way to easily track the ballpark’s revenues and expenses to ensure the project does indeed pay for itself, with officials planning on setting up such accounts midway through the team’s second season.

“I had hoped those accounts would have been set up when I started with the city,” said Tim McGourthy, the City of Worcester chief financial officer, who started his job on June 22, 2020.

The North Star

When the then Pawtucket Red Sox announced in August 2018 they would move into a new Worcester-built stadium for the 2021 baseball season, Augustus said the project would pay for itself, with the taxes and other municipal revenues generated within a special tax district surrounding the ballpark slated to exceed the cost to build the stadium.

Over the next three years, Augustus would repeatedly call this promise his North Star in all decision-making, even as unexpected obstacles caused costs to swell to a point where the special tax district had to be expanded and Polar Park is now the most expensive minor league ballpark ever built.

With construction finished, Augustus said this remains his guiding principle.

“At the end of the 30 years, it is going to be more profitable than we initially thought,” Augustus said.

The city’s ability to generate revenue inside the ballpark tax district has less to do with the team’s ability to attract fans, and is more greatly tied to new commercial and residential developments within the tax district. While a portion of the city's revenue plans include parking fees, taxes on concessions, and the WooSox annual lease payments, the bulk of the money used to pay down the city’s bonds will come from property taxes.

Initially, when the team announced its move in 2018, the development designed to generate the necessary tax revenue was a $125-million plan from Boston developer Madison Properties, which included hotels, apartments, retail, restaurants, and office space. In the three years since, that proposal has shrunk and its various elements have been delayed.

However, two new proposed developments in the ballpark district are expected to make up the shortfall caused by the changes in Madison’s project, Augustus said. The first is a $110-million, 13-story apartment-and-retail tower called The Cove from Worcester developer Churchill James LLC. The second is a 400-unit housing complex from Boston Capital Development on the former site of the Table Talk Pies manufacturing facility.

Any other developments moving into the ballpark district over the course of the next 30 years will help cover the stadium costs as well, said Peter Dunn, chief development officer for the city.

First-year shortfall

When the city knows in advance a major multi-million dollar project is coming, it can set aside money to help meet the initial phases of its long-term debt obligations, Augustus said. Because of the relatively short three-year window between the team’s 2018 announcement and Polar Park’s opening, the city didn’t have time to set money aside for what grew into a $160-million project.

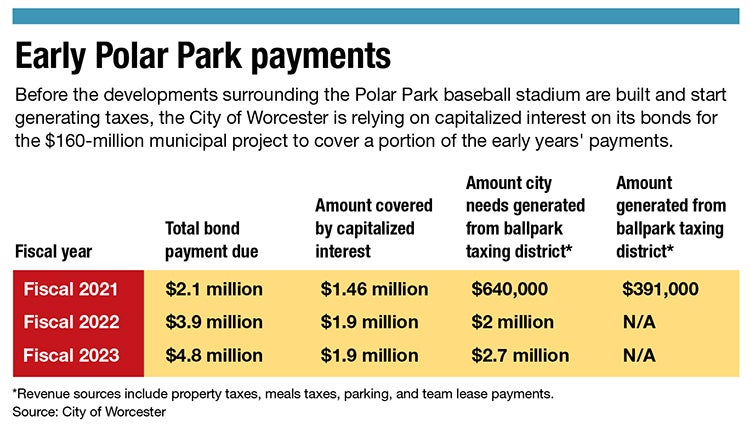

Instead, the size of the annual payments for the first few years of the city’s 30-year debt obligations are smaller than what they will average over the life of the repayment plan. The city is relying on a generally accepted accounting practice of capitalized interest to cover a significant portion of those early year payments.

The practice of capitalized interest essentially uses part of the loan to pay off an earlier part of the loan. The City of Saint Paul, Minn. used capitalized interest for the first 1.5 years of paying down the construction costs of CHS Field in 2015, which after Polar Park is the most recently built city-owned Triple-A minor league baseball stadium.

Victor Matheson, a sports economist at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, who has been skeptical of the city’s promise to have the stadium pay for itself, said capitalized interest is a normal way to finance major projects.

“With any big construction project, you need the money for construction before the revenue from the project starts coming in,” he said.

Despite capitalized interest covering 70% of Worcester’s obligation for the stadium debt payments in fiscal 2021, the city didn’t generate enough other revenue inside the ballpark district to cover that first payment. For that fiscal year, which ended on June 30 about halfway through the WooSox inaugural season, the city needed the district to generate $640,000. Instead, the city got $391,000.

However, the city didn’t need to dip into its general fund to cover the shortfall, thanks to the planned Churchill James development, Dunn said. The developer needed a property the city originally obtained for the stadium, and bought it on Dec. 1 for $3 million, which was put into a fund to offset the first-year ballpark revenue shortfall, and any future shortfalls in stadium debt obligations.

Augustus said the $3-million sale occurred almost by happenstance, as the city never considered buying properties just to sell at a profit to fund the ballpark. The city didn’t originally want to purchase the properties at 85 Green St, 2 Plymouth St., and 5-7 Gold St. for the stadium, but bought them for $10 after the owners of those properties insisted the city include them in a package deal for land the city did want.

“We ended up buying more than we needed for the ballpark, but it ended up working out in our favor,” Augustus said.

Team-friendly lease

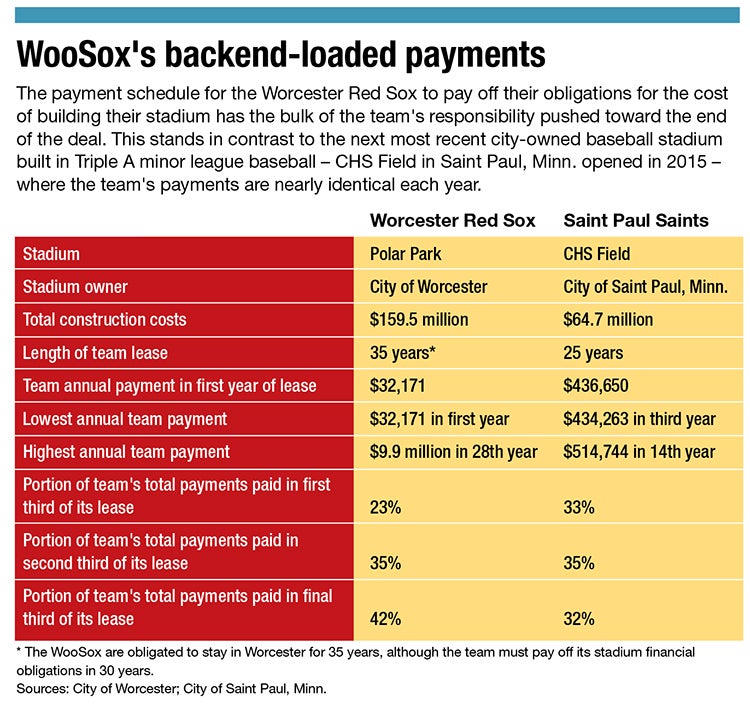

The WooSox are responsible for more than $60 million of Polar Park’s cost, but the team’s contribution toward the fiscal 2021 debt payment was $8,043. For calendar year 2021, which includes the entirety of the team’s inaugural season, the team’s total lease payment is $32,171.

This significantly below-average annual payment is due to how the team’s lease with the city is structured, where the bulk of its financial obligations are reserved toward the end of the deal. The payments steadily increase each year, with 42% of the WooSox total responsibilities being paid in the last 10 years of the contract, including a $9.9-million payment in the lease’s 28th year. The team and the city can renegotiate the lease terms at any time.

The WooSox requested the lease be structured this way, said Augustus, as the team planned for problems arising with moving into a new ballpark.

“We knew the first couple of years, we would have to work some bugs out,” Augustus said.

WooSox officials declined to comment for this story.

This backend-loaded lease agreement runs in contrast to the deal the St. Paul Saints struck with the City of Saint Paul, Minn. Under that agreement, the Saints pay nearly identical $450,000 payments every year for 25 years, with the total payments being slightly higher near the start of the lease than at the end.

When the cost of Polar Park rose to $160 million in January, the WooSox agreed to extend their obligation to stay in Worcester from 30 year to 35 years, although the payment schedule runs for only 30 years. This is because the team must pay off its portion of the stadium costs within 30 years. After that is complete, the city and the team will have to negotiate a rent payment for those last five years, said Augustus, who added those negotiations are unlikely to occur while he is city manager.

“I definitely don’t plan on that, as I will be in my late 80s by then,” he said.

Tracking ballpark district finances

Even though Augustus has called the stadium paying for itself his North Star, the city doesn’t have revenue and expenses accounts set up to ensure that is 100% true, as Worcester is relying on what McGourthy, the city’s CFO, describes as the spreadsheet approach.

City officials are simply tracking the ballpark expenses and the district revenues to ensure the project pays for itself, McGourthy said. The ballpark tax district won’t have a separate account set up in the city budget until fiscal 2023, which starts on July 1, 2022.

The main reason for this delay is the stadium is still a construction project run by the Worcester Redevelopment Authority through the end of calendar year 2021. After, the ballpark district will transition over to the city budget, where it will have a separate account.

The delay gives the city time to work out logistics problems on the ballpark district revenues, Augustus said. The main issue is a 0.75% city-imposed sales tax on restaurant meals inside the stadium and the ballpark district, which is supposed to help pay the debt.

The Massachusetts Department of Revenue collects this meals tax citywide and disperses it to the City of Worcester in one lump sum. By fiscal 2023, the city hopes to have worked out a solution with DOR to parse out which revenue came from inside the ballpark district.

For fiscal 2021, the city projected meals tax would generate $17,000 from stadium concessions and another $20,000 from restaurants outside the stadium but inside the ballpark district.

Augustus and McGourthy were further encouraged about the stadium’s ability to pay for itself because parking fees for the city came in at $188,364 for fiscal 2021, which was 61% higher than expected. They were encouraged because parking is the main aspect of the city’s 30-year debt repayment plan most tied to the number of fans coming to WooSox games, and that increased revenue came during the portion of the baseball season where the number of Polar Park fans were limited due to coronavirus restrictions.