As the cost of leased housing has risen and wages have stayed relatively stagnant, the portion of Worcester renters who are overburdened by the cost of their homes has risen to 51%.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Rising rents in Worcester are hitting residents at every income level.

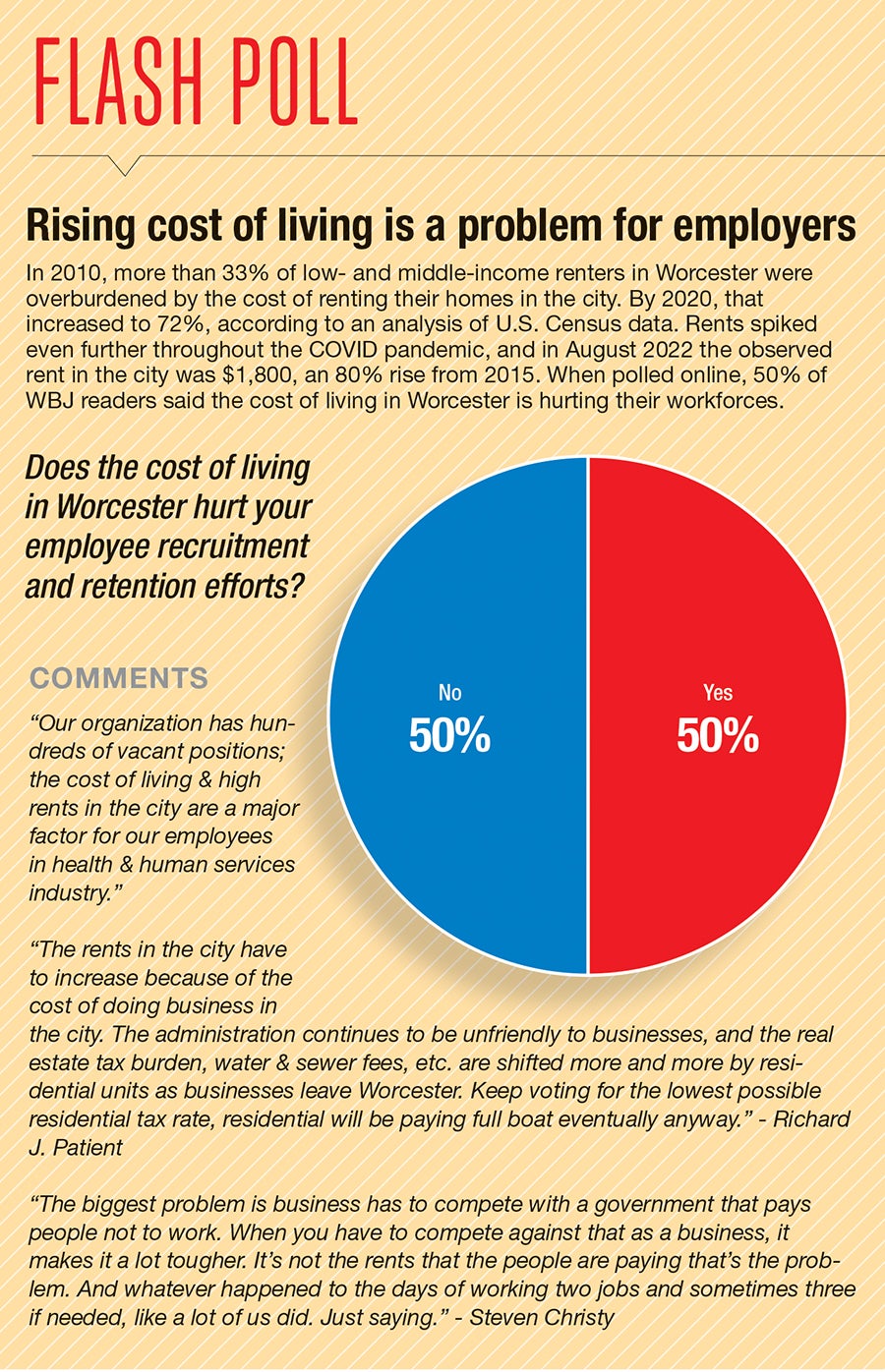

As the cost of leased housing has risen and wages have stayed relatively stagnant, the portion of Worcester renters who are overburdened by the cost of their homes has risen to 51%, a rise of 6% from 2010 to 2020 and outpacing nearly all comparable cities in Central Massachusetts and the Northeast.

For businesses in and around the city, the increasingly unaffordable costs for their employees to live in Worcester compounds their workforce problems, still exacerbated by the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic and other issues like childcare costs, said Alex Guardiola, vice president of government affairs and public policy at the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce.

“You see this in the area’s industrial and manufacturing sectors, hospitality, and especially in health care,” Guardiola said.

Worcester Business Journal has partnered with the nonprofit Worcester Regional Research Bureau on this report “Redlining: An Economic Legacy” to examine the impact of rising rental costs in the city, along with the historic decisions that have led to specific neighborhoods and people of color to disproportionately bear the brunt of the issue.

“As householders spend higher and higher percentages of their income on household costs, they necessarily must make trade-offs in other areas of their lives,” WRRB writes. “Thus, cost-burden has the effect of exacerbating income inequality and inhibiting asset growth; people need a place to live, and may cut back on other areas of spending in order to pay increasingly high household costs.”

Losing the affordable mantle

Worcester has long been considered an affordable alternative to Boston, and while rents in Worcester do not yet match those in Boston, other communities like Fitchburg, Leominster, and Clinton are touting their affordability, challenging Worcester.

As part of its partnership with WBJ, the Worcester Regional Research Bureau released its new report “Static Income, Rising Costs: Renting in the Heart of the Commonwealth” on Dec. 12 laying out how Worcester has become increasingly unaffordable for renters, while homeowners have seen their costs decrease.

Worcester rents grew 80% between 2015 and 2022, reaching an average of just over $1,800 per month, according to Zillow’s Observed Rent Index.

Over roughly the same time period, Worcester renters saw their incomes increase by 1.45% between 2010 and 2020, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

This has led to more than half of Worcester renters being cost-burdened, meaning more than 30% of their incomes are spent on housing costs.

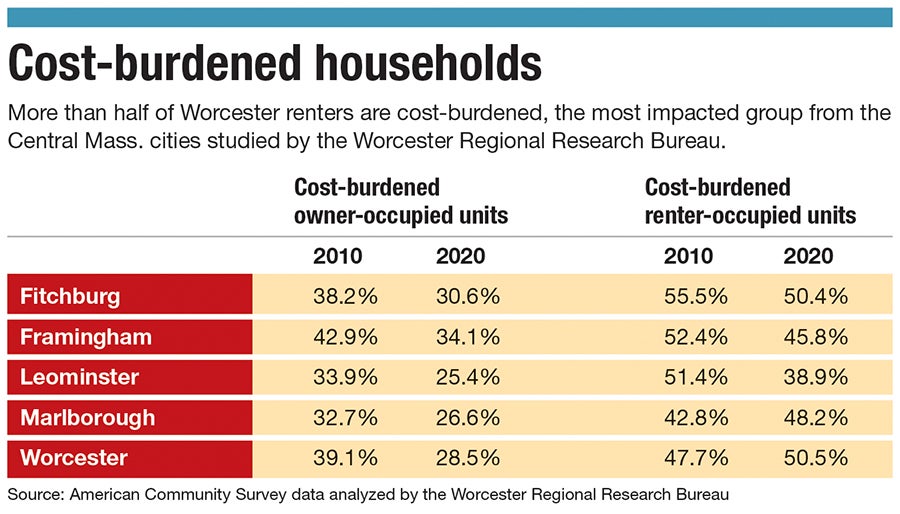

Around the major cities in Central Massachusetts, Worcester has the highest percentage of cost-burdened renters, as Fitchburg (-9.17%), Framingham (-12.58%), and Leominster (-24.36%) all saw a significant drop in the percent of cost-burdened renters between 2010 and 2020, and Fitchburg is the only other city with more than half of its renters spending more than 30% of their income on housing costs.

Marlborough (12.5%) was the only city other than Worcester examined by WRRB with an increase in cost-burdened renters, but less than half of the MetroWest community’s renters are hampered by housing costs.

While he doesn’t have specific data showing the high cost of living is affecting Worcester’s workforce, Jeffrey Turgeon, the executive director of the MassHire Central Region Workforce Board, cautions about what he saw while vacationing in Maine.

In Maine, the retail, food service, and hospitality businesses were having a difficult time finding workers because they can’t afford to live near their jobs or there just aren’t enough affordable units, Turgeon said.

“These are jobs that pay barely enough to live,” said Turgeon, “They’re not the kind of job you’re going to travel for.”

Looking further out, WRRB found of cities in the Northeast with populations within 20,000 of Worcester and more than 55% of units renter-occupied, the cost is rising fastest in Worcester.

Between Lowell, New Bedford, Quincy, Springfield, Providence, and Rochester, New York, the only other city where the number of cost-burdened renters rose was in Lowell, with a 0.13% increase, compared to Worcester’s 5.87% jump.

Springfield and Rochester were the only other cities where more than half of renters are cost-burdened.

The heaviest burden

The cost of living makes it harder to recruit people to work at Quinsigamond Community College in Worcester, said Michelle Tufau, QCC’s associate vice president for student success. The school recruited two new staff members from out of state, and they were very surprised at the cost of living in the area.

The high cost of living impacts the college in a number of ways, Tufau said.

Students are reducing the number of credits they are taking per semester, she said. The average is down to nine credits versus 12 in the past, as students were once able to work a part-time job to make ends meet while they were in school.

More students are living in their cars or couch surfing, unable to find adequate affordable housing, she said. The number of food assistance applications from students has increased.

“You really see it in the use of student services. We’ve seen a 61% increase in student usage of our food pantry,” said Tufau, though she said the actual use is greater because QCC provides food to other members of the community as well.

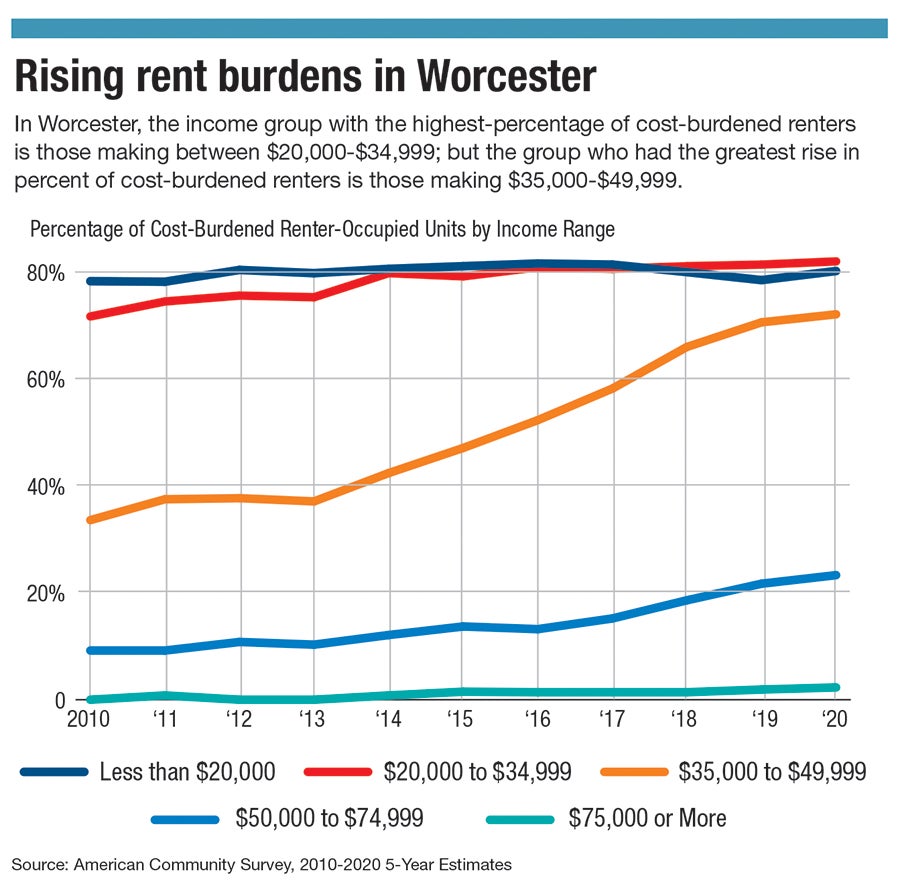

The WRRB report breaks down the percentage of cost-burdened renter-occupied units by income levels and tracks the changes over the period between 2010 and 2020. The report found more than 80% of renters making less than $35,000 annually were cost-burdened, and the number of units in this demographic decreased by 1,717 over the 10 years.

The income groups facing the biggest increase in percentage of cost-burdened rental units are people making between $35,000 and $75,000.

The lower end of this group, making up to $50,000, saw the percentage of cost-burdened units more than double from 34% to 72%.

Renters at the top income level, making over $75,000 per year, saw the biggest increase in the number of units, adding 3,684 units, and the portion of those renters who are cost-burdened remained low, although it still rose from zero to 2.3%.

Homeowners are faring much better than renters in terms of being cost-burdened, but there are fewer of them in 2020 versus 2010.

The percentage of homeowners who are cost-burdened has dropped significantly (from 39% to 29%) over the period between 2010 and 2020, but the number of owner-occupied units in the city dropped by more than 8%. Owner-occupied units make up the minority of Worcester housing, comprising 42%.

The number of renter-occupied units climbed almost 12.5% since 2010 solidifying Worcester as being a majority renter-occupied city.

“We need to build housing at all income levels, but we need to build affordable housing at the same rate as market-rate housing,” said Leah Bradley, CEO of the Central Massachusetts Housing Alliance, a nonprofit in Worcester dedicated to preventing homelessness.

Cost-burden and lack of affordable housing stock puts a lot of people in real danger of becoming homeless, said Bradley.

“The Department of Housing and Community Development is under a pretty significant crisis. The shelters are full. We are using hotels and motels again, which we haven’t had to do in years,” said Bradley. “Folks just can’t afford rent anymore, and one of the issues that we’ve seen is that there’s a lot of folks coming in with no-cause evictions.”

Sometimes when landlords want to renovate a building, they don’t renew the leases of tenants, Bradley said, and much of the housing stock in Worcester needs renovation.

But, because of the increase in rental costs, tenants are not always able to find a new apartment they can afford. The same thing occurs with disasters like fires, or the July apartment collapse on Mill Street in Worcester, which displaced more than 100 residents.

Some of these people move into family shelters or out of the city into surrounding towns, while the less fortunate among them end up on the street, said Bradley.

Solving the affordability problem

The Worcester chamber has been advocating to build more housing in the city, including more affordable housing where the rents are capped based on household income, said Guardiola.

“We realized when the city started this period of rapid growth 10 or 15 years ago that we were going to need more housing,” said Guardiola.

The chamber is backing the City of Worcester’s effort to adopt inclusionary zoning, a policy requiring new residential developments to set aside a number of affordable units for residents who make under a specified income. The Worcester City Council is in the process of making inclusionary zoning into policy.

It is likely to pass in some form, but the terms are being negotiated.

To conclude its report, WRRB touted the City’s inclusionary zoning efforts, as well as Worcester’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund to incentivize the construction of affordable units. Grants from the program will fund either 25% of the cost of an affordable unit or $150,000, whichever is less, according to WRRB.

In addition, WRRB said the Commonwealth of Massachusetts could increase funding for its Housing Development Incentive Program from $10 million to $30 million, which could facilitate construction of all types of units in Gateway Cities like Worcester.

“Concentrating on raising household incomes, slowing cost-growth, addressing the concerns of the most vulnerable residents, and increasing the number of available units should go a long way to ensuring that Worcester’s housing and economy remains strong in the future,” WRRB wrote.