Finding stable housing has always been a challenge for low-income earners, but the problem has ballooned in places like Worcester where the average rent is growing about 10 percentage points faster than the average income.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

In his first full season as a minor league baseball player, Worcester Red Sox relief pitcher Geoff Hartlieb found out where he’d be playing for the season 24 hours before he left. He arrived in Charleston, W.Va. with no car and no apartment lease.

“We saw a ‘For Sale’ sign on an apartment, not a very nice place, and they let us live there with four guys in there for like $200 bucks apiece,” Hartlieb recalled. “We had cardboard boxes as nightstands from our stuff. Not a house, not a living situation.”

At the time, Hartlieb was making $11,000 in salary a year.

Finding stable housing has always been a challenge for low-income earners, but the problem has ballooned in places like Worcester where the average rent is growing about 10 percentage points faster than the average income, according to 2020 U.S. Census Bureau data. The problem is beginning to touch middle-income workers, too, as the average cost of a single-family home in the city surpassed $350,000 in March, according to Peabody real estate data provider The Warren Group. As an increasing number of workers are unable to afford housing, a few employers are taking the extra step to establish housing assistance programs.

In November, Major League Baseball announced a new policy providing free, furnished housing to 90% of its minor league players. With Worcester’s tight rental market, it was no easy feat to secure housing for the more than 30 players on the WooSox, but it has made a significant difference in many of the players’ lives, said WooSox infielder Ryan Fitzgerald.

“I made the mistake of signing the seven-year deal at 23. I’m locked in making $2,400 bucks a month until I’m 30,” said Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald’s $2,400 monthly salary is actually twice what it was during the last four seasons he’s played, as the MLB’s new policy increased salaries between 38% and 72%, along with providing housing.

Without the housing assistance, all but $300 of Fitzgerald’s monthly paycheck would go toward rent at Chatham Lofts, where the infielder was placed by the team. The newly built apartment units rent for an average of $2,147, according to the complex’s developer, the Menkiti Group of Washington, D.C.

“Covering the housing, I mean, the money is one thing, but the stress of having to find a place and then furnish it … I would have just lived in a hotel again,” he said, adding he spent up to $100 a night to live out of a hotel in Worcester before the MLB policy was established.

Housing & labor

While professional baseball has some instability and burdens most other jobs don’t, housing that’s affordable to local workers touches nearly every industry. Yet, in Worcester, it’s becoming an increasingly out-of-reach commodity, said Lindsay Richmond, deputy director of housing counseling at RCAP Solutions, a housing nonprofit based in Worcester.

“Now, landlords are putting forth additional requirements to accept new tenants: things like, you need to make three times the rent in income,” Richmond said. “Middle-income people are being pushed out of the homeownership market by people who could come in with $500,000, all cash.”

For both low- and middle-income workers, housing is getting more unaffordable in Worcester, threatening to push workers into cheaper suburbs, Richmond said.

“If we lose all of these regular people in Worcester, who’s going to staff the kitchens and the restaurants and the gas stations and things like that?” she said.

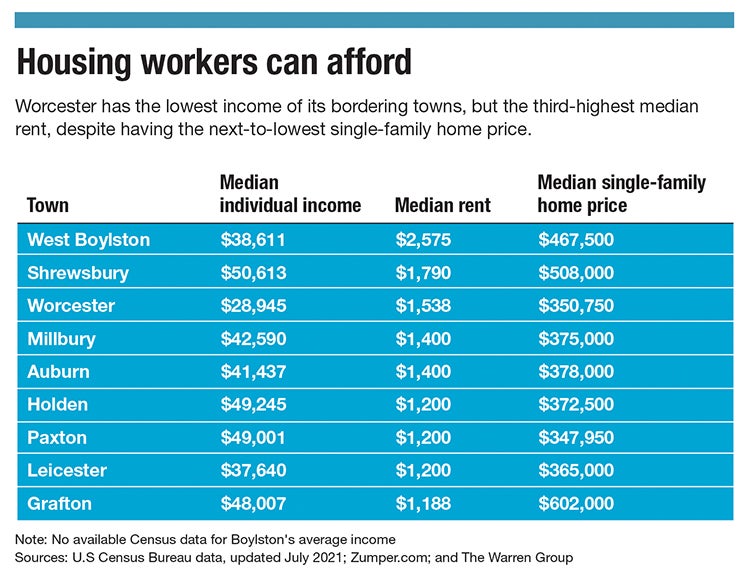

With a $28,945 median per capita income, Worcester has the lowest average income compared with its eight bordering towns, according to the Census. Meanwhile, rents in the city have risen 14% in the last year to an average of $1,538 per month, according to Zumper.com.

As rising housing costs progressively price workers out of the city, employers are faced with the question of when to step in and offer assistance.

“The costs are obviously going up across the board in Massachusetts, so it’s definitely something that employers should consider when they’re thinking about their workers and their housing situation,” said David Sullivan, economic development and business recruitment associate at the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce.

In a 2019 report on workforce housing, the Worcester chamber highlighted the benefits of employer-assisted housing, looking at the bottom-line advantages for companies when employees have affordable, close-proximity housing.

Since that report was released, the 2020 Census data revealed Worcester was the fastest-growing major city in New England, with a 14% population increase over the past decade. Roughly 25,000 people moved to Worcester, but the housing stock increased by 10,000 units in the same amount of time, creating a massive strain on supply, Sullivan said.

Feasibility for employers

Providing housing to workers presents a massive challenge for most employers, especially in Worcester where the rental vacancy rate teeters around 4%.

For the WooSox, it took a Herculean team effort to provide housing to all players by the start of the season, said Lisa Jacobs, a Realtor at Keller Williams, Pinnacle in Worcester, whom the team chose to procure the housing.

“Housing is very, very tight here. It’s very difficult, but we did it,” said Jacobs, who found 33 beds for players in less than three months. “A lot of the stuff I found was off-market … It came down to the relationships I have built over the years.”

Although the burden of housing affordability isn’t unique to the WooSox, the MLB’s ability to provide free housing is unusual. Most small businesses would find it economically infeasible to provide housing assistance, much less free housing, said Sullivan.

“A lot has changed since [the 2019 chamber housing report came out]. With the increases in inflation and the costs of pretty much everything, including labor and benefits, it would be really difficult for a small business to help with housing assistance for their employees,” he said.

Instead, Sullivan said the chamber’s most recent efforts have gone toward promoting condominium construction in Worcester. Under a new state program called Commonwealth Builder, developers would receive financial incentives to construct workforce condos catered toward people with incomes around 60% to 120% of the area median income.

Employers can offer educational programs to help workers connect with landlords or learn about home buying, Richmond from RCAP said.

Ultimately, though, the employers who may feel the effects of losing workers to cheaper suburbs are not the ones with power over the system, Richmond said.

“The bottom line is, we need more housing,” she said.