It is impossible to extricate the history of Hopedale, a town which is home to just shy of 6,000 people, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, from the Draper Corp., which most locals refer to as the “Draper mill,” or, simply, “Drapers.”

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

On Aug. 25, 1978, Rockwell International sent a letter to employees at its Hopedale plant, notifying its 600 workers of the company’s plan to consolidate its manufacturing operations elsewhere.

Rockwell, which purchased control of Draper Corp. in 1967, cited several reasons for this closure, including what it called the energy crunch of 1973-74, increased foreign competition, and the expenses of maintaining the plant, which was over 60 years old at the time.

“By this letter, we wish to assure you that the company’s tentative decision to consolidate operations was reached only after most careful study and consideration of every aspect of Rockwell-Draper’s ability to continue a viable business,” the letter, signed by General Plant Manager Alex Archer, said.

Then-chairman of Hopedale’s board of selectmen, John Hayes, told reporters during a press conference regarding the closure, according to Milford Daily News reports from the time, Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulations, as well as state and federal noise pollution standards, had made Draper fly shuttles impossible to use, and therefore sell, to the customers that bought them. The town’s defining business landmark would close, leaving the already sleepy, tree-lined mill town even sleepier.

Two years later, a separate Milford Daily News article commemorated the last two employees leaving the 1.8-million-square-foot building.

And now, by the end of June 2021, four decades after those employees locked up for the final time, that complex is slated to be wholly demolished, making way for a development whose details have yet to be finalized.

Making a company town

It is impossible to extricate the history of Hopedale, a town which is home to just shy of 6,000 people, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, from the Draper Corp., which most locals refer to as the “Draper mill,” or, simply, “Drapers.”

The town’s relationship with the Draper family goes back to Hopedale’s founding, between 1841 and 1842, initially conceived as a Christian, semi-socialist commune, founded by writer and minister Adin Ballou, and established on a large parcel of land in what was still part of Milford. Its members were pacifist abolitionists who believed in temperance and women’s rights. The settlement was referred to as the Community, and was one of several to pop up at that time.

“We are a little wild here with numberless projects of social reform,” Ralph Waldo Emerson famously wrote of New England in 1940. “Not a reading man but has the draft of a new community in his waistcoat pocket.”

Ebenezer Draper, a manufacturer, and his wife, Anna Thwing Draper, were regular attendees at the First Church in Mendon, where Ballou was pastor prior to founding Hopedale. When Ballou announced his plans to start the Community, according to Ballou’s writings, Ebenezer and Anna joined him in 1842.

Ebenezer, widely hailed as a deeply religious man, brought with him a patent for a loom temple, inherited from his father, which was then manufactured in Hopedale. He used its profits to support the Community. Effectively, this was the very first Draper mill in Hopedale, and Ebenezer later succeeded Ballou as president of the Community in the 1850s.

In 1853, Ebenezer’s brother, George, who had been working for manufacturer Otis Co. in Ware, joined his brother in the Community, and the two got into business. Three years later, the pair owned as much as three quarters of the Community’s joint stock. But after reporting the village was in dire financial straits, they assumed the Community’s debts and effectively ended Ballou’s experiment, as well as one of the region's longest-running socialist communes.

Accounts differ on whether the Draper brothers, and particularly, George, folded the Community intentionally or not, in pursuit of business prosperity. Notably, George’s wife, Hannah Thwing Draper, Anna’s sister, refused to ever join it in any formal capacity because, according to her son William Draper’s autobiography, “she did not believe all questions should be settled by a majority vote or that there should be no rewards for pre-eminent ability and services.”

In 1856, following the commune’s end, the Draper brothers opened Hopedale Machine Co., improving their loom products and growing their operations.

“They kind of owned the little shops they had there at the time, and then they started building up there,” said Hopedale resident and local historian Dan Malloy, who runs a digital archive of the town’s history.

Ebenezer ultimately retired in 1868, selling his interest to George, who in turn sold it to his son, William, according to a 2001 National Register nomination.

Shortly thereafter, the Draper family led the push to officially separate Hopedale from Milford, which was finalized in 1886, through an act in the state legislature.

“It was pretty clear that the Drapers, they were pushing to have their own town,” Malloy said.

Both Ebenezer and George died the following year.

Draper Corp. is born

By the turn of the 20th century, the Draper family had grown substantially, and the company absorbed a number of area manufacturers, officially organizing as Draper Corp. in 1916. The company was widely known by that time to be the largest manufacturer of automatic cotton looms in the world.

The Drapers had made a name for themselves, boasting influence both in and out of the manufacturing sphere, including William F. Draper, a Civil War general who later served as a U.S. congressman and ambassador to Italy, as well as Eben Sumner Draper, who served as the 44th governor of Massachusetts beginning in 1908, and Princess Margaret Draper Boncompagni, who married Prince Andrea Boncompagni of Rome in 1916.

Notably, Gov. Draper and his wife donated the original land and buildings used to establish what is now Milford Regional Medical Center in 1903.

In many ways, the Drapers were Hopedale. The Draper company, according to a 2007 report from the state Department of Conservation and Recreation, “paved 12 miles of streets, installed granite curbs and sidewalks, laid out municipal parks, built a sewage system and laid water and gas lines.”

The business built and maintained housing for its workers, often in the form of duplexes, or double houses, many of which stand today. According to the 2007 DCR report, one cluster of 30 double houses near Hopedale Pond, dubbed the Lake Point Development, was a landmark in the design of company housing. The Drapers, per Malloy, would eventually sell these homes by the half between 1955-1954, sometimes to the workers who lived in them.

The Draper family, over the years, donated the town hall, the Hopedale Community House and George Albert Draper Gymnasium, temporary library space (a president of Draper Corp., Joseph Bancroft, built the Bancroft Memorial Library that stands today), as well as the town’s Unitarian church, which now houses the Hopedale Unitarian Parish.

During the company’s heyday, many town buildings were heated by the Draper Co., whether or not they were Draper built or owned, through underground steam pipes, said Malloy, which caused a challenge for property managers as the company began to shutter.

“They all had to put in heating systems they hadn’t had before,” he said.

A sputtering stop

As the textile business began moving south, Draper followed suit. Layoffs, Malloy said, began in dribs and drabs.

“People knew it was going downhill, certainly, before it did,” he said. “There were a lot of Milford news articles, and the company was always denying them.”

Draper enticed some of its Hopedale workers to move to South Carolina, where the company maintained operations. Some, Malloy said, took the bait. Others turned to the technology and electronics industry, which was cropping up in Massachusetts along Route 128, which first opened in 1951.

Malloy, who attended school in Hopedale, said his classmates’ fathers worked at Draper around this time. Over the next three decades, the struggling company was sold, eventually closing its Hopedale operations completely in 1980. The business, which had virtually built the town from the ground up, supported its infrastructure, and maintained the community through a paternalistic partnership, at one time employing as many as 4,000 people in and around Hopedale, was no more.

“All of the industry was looking for a more economical way to keep themselves in business,” said Jeannie Hebert, president and CEO of the Blackstone Valley Chamber of Commerce. “Wages were lower, and it didn't cost as much in taxes to be in the South.”

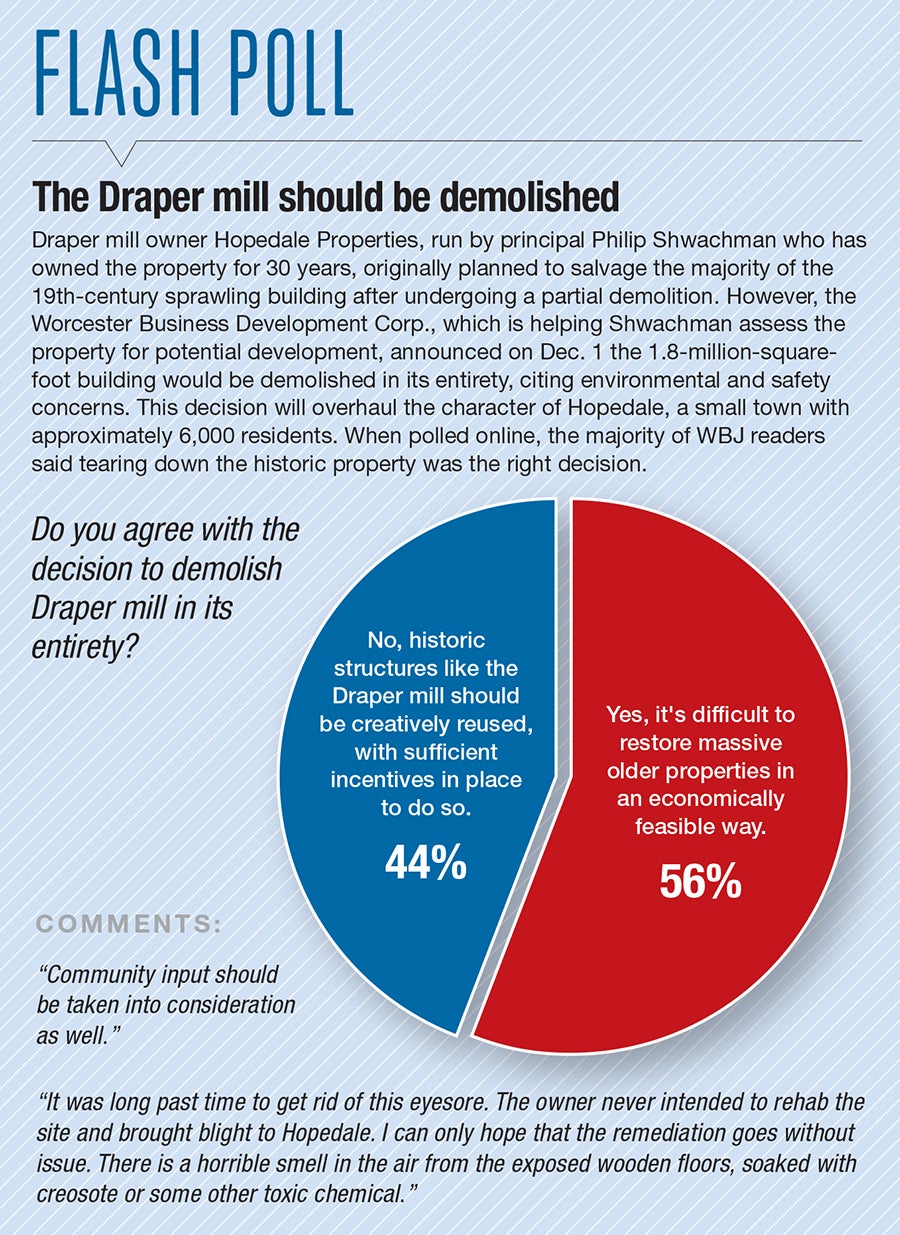

On Dec. 1, 2020, Hopedale Properties, which is run by principal Philip Shwachman, announced the entire Draper building would be demolished, after announcing three months earlier it would take down only a quarter of the remaining structure. Shwachman, who bought his first Hopedale property in 1990, a decade after Draper shut down, said he was not familiar with Hopedale prior to that purchase, but that he was looking forward to developing the land.

“It is not often that the opportunity to revitalize the core downtown of a community arises,” Shwachman said in an email. “Given the large acreage we have, we are excited by the opportunity presented and look forward to working with the Community (sic) envisioning the future.”

The announcement has triggered mixed reactions from local residents and others invested in the social, historical and economic wellbeing of both Hopedale and the Blackstone Valley. Hebert, who said she was sad the structure was coming down in full, said she hoped the Draper legacy would be commemorated, such as with a brick courtyard built from the mill’s remains.

“There’s a lot of fond memories,” Hebert said. “There’s a lot of families whose entire history was… at the Draper mill because the mills were a way of life.”

Still, she said, the development of the land will likely be a net positive both for Hopedale and the region, citing the current upswing of manufacturing in Central Mass., following periods of uncertainty in recent decades. She pointed to the Worcester Building Development Corp., which is helping Shwachman fix up the property, as well as the Central Massachusetts Regional Planning Commission, which she expects to be mindful of the area’s needs.

The future of the Draper property remains unknown, but what is clear is the town likely would never have existed without it. As in other towns in the region, among them Whitinsville, which housed Whitin Machine Works, or Webster, the home and final resting place of Samuel Slater, known famously as the father of the American Industrial Revolution, mill work and life in Central Mass. were one in the same.

“It’s always sad to say goodbye to an old friend,” Hebert said.