For decades, women have been moving closer to equality with men in the workplace, particularly in workforce participation and pay. A once-in-a-century pandemic has undone much of that progress.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

For decades, women have been moving closer to equality with men in the workplace, particularly in workforce participation and pay. A once-in-a-century pandemic has undone much of that progress.

The coronavirus pandemic-related recession has been so disproportionately brutal to female workers the downturn has even earned a nickname: the shecession.

A few major reasons explain why: Women are more likely to work in hard-hit industries such as accommodation and food services or health care, and they’re less likely to work in jobs allowing for telecommuting. They’re also far more likely than men to have to care for a child, who during the pandemic may not be able to go to school or daycare.

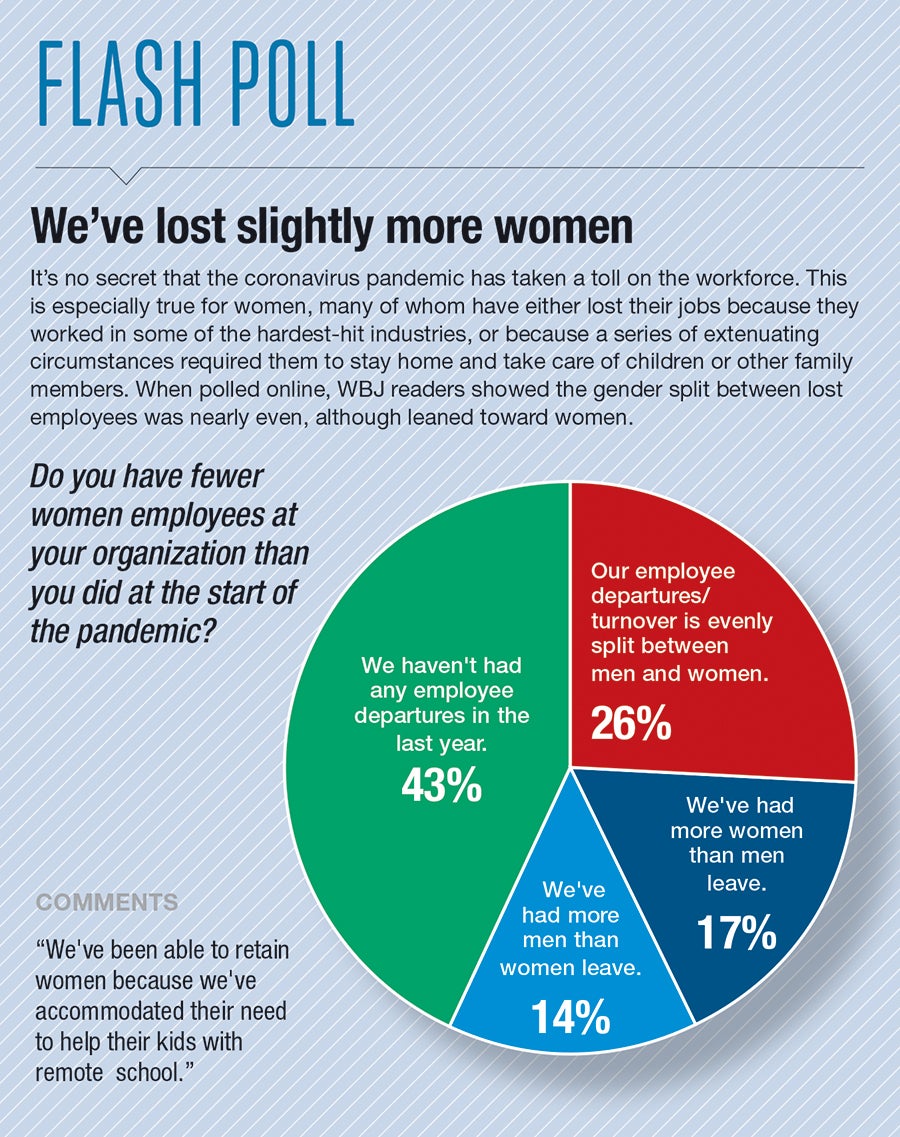

Through last summer, women made up 54% of jobs lost during the pandemic, according to the New York management consulting firm McKinsey & Co.

“If you look at the number of jobs and the gains they made in the last 10 years, they’re all gone,” said Nancy Nager, president of the female worker advocacy group The Boston Club.

Bruce Mendelsohn, a resource development coordinator with the Worcester-based MassHire career center office, sees the hit as even more severe, gauging in large part by female workforce participation rates, which at one point hit a low not seen since 1988.

“We’ve turned the clock by at least a generation,” he said. “If you're in a running race, and you've started walking, you've fallen behind the leaders. Women in this case aren't just walking, but they're walking backward.”

Reversing long-fought-for progress

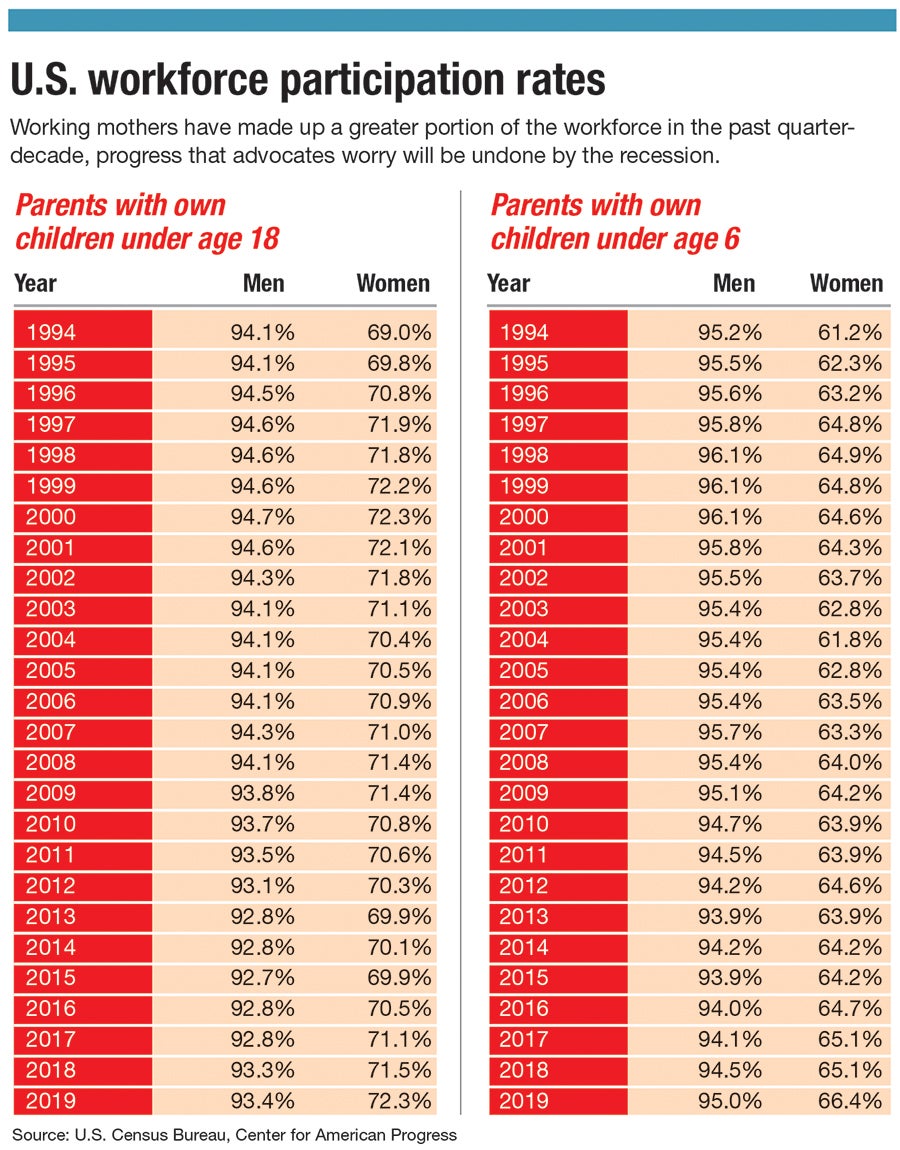

Women were slowly but consistently making up a greater share of the U.S. workforce before the pandemic hit.

In the quarter century ending in 2019, working women with children under 18 at home made up an extra 3.3 percentage points in labor force participation, according to the U.S. Census Bureau and the Center for American Progress. For working moms with children under 3 at home, the jump was 5.2 percentage points.

By 2016, women outnumbered men in the workforce, 51.7% to 48.3%, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Now that may be at risk.

For the first time, a recession is disproportionately hitting women, according to a National Bureau of Economic Research study. In the past, downturns tended to hit male-dominated industries such as manufacturing and construction. This pandemic recession, though, has hit service jobs, as well as health and education – fields where women professionals are more common.

Even those whose industries have been largely spared are now sometimes having to balance work requirements with new needs at home. That’s made the hit of the recession felt everywhere from entry-level work to the most career-driven women.

A study by Northeastern University in Boston late last spring, while the pandemic was still in its early stages, found working parents lost an estimated eight hours of working time every week while trying to squeeze in their professional duties and what needed to be done at home. Roughly 13% of those working parents said they had to either reduce their hours or leave their jobs entirely to care for their children.

There's no small number of women in that situation. One in four working women have a child under 14 at home, and two-thirds of those rely on child care or schools, according to the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.

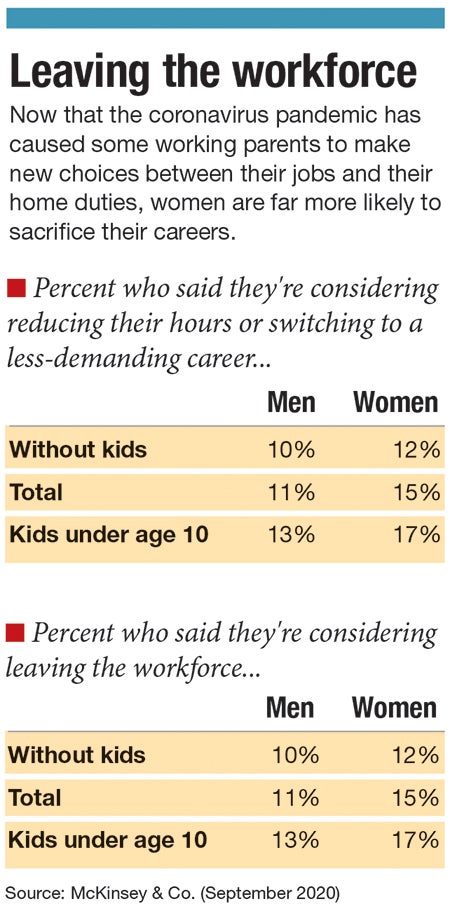

When working parents of younger children consider leaving the workforce, it’s almost twice as likely to be the woman who gives up her job, according to McKinsey. A study from the firm last fall found 23% of women with children under 10 considering leaving the workplace, compared to 13% of men in the same situation.

Even those without children are reporting greater strain these days, said Jean Beaupre, an associate professor of communication and marketing at Nichols College in Dudley who closely researches the issue of gender in the workplace. Routines have shifted, working hours have stretched on, and a need to always be available has only worsened, she said.

“The result is the potential for burnout as well as impact on their future careers,” Beaupre said.

It doesn’t appear as if women have been regaining jobs at the same disproportionate rate they were losing them at the start of the pandemic, either. A report issued in October by the Women’s National Law Center found women to make up four out of five of those who stopped looking for work in the prior month, just as some schools were returning for the year.

Not only might women struggle to re-enter the workforce, but their pay is likely to suffer, too.

A 2018 report by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research found women who missed even just one year of working had annual earnings 39% lower than those who never left the workforce. Those gaps are common. Even before the pandemic, 43% of female workers had such a stoppage in their career, double the rate of men, the report found.

Helping women get back to work

Researchers and advocates worry the damage from the recession could be long-term, and a range of potential fixes have already been floated.

“There could very well be a pandemic-fueled gap in the leadership pipeline, the result of which may not be seen in the upper ranks for a number of years,” Beaupre said.

Complicating women’s return to the workplace post-pandemic will be an expected lingering use of remote work, Beaupre said. That could make it harder to understand how women navigate and develop their careers when there will be less in-person face time with management.

Evelyn Murphy, a co-chair of the Boston Women’s Workforce Council, put the pressure on businesses who will have an opportunity once employment increases again to remake their hiring practices to better account for women who balance family needs at home. Employers need to be more attuned to child care support, for example, she said, or to putting women into leadership positions who can then better prioritize such needs.

“Unless they’re there to design those policies,” Murphy said of women, those policies “are going to continue to have biases in them.”

Murphy said she’s not very optimistic employers will quickly change post-pandemic, or that the federal government, focused on vaccination efforts and other immediate needs, will soon take up the challenge.

McKinsey, the management firm, has urged a proactive response from governments to get women back into the workforce in a better way. Without intervention, McKinsey said, “this would not just set back the cause of gender equality but also hold back the global economy.”

Doing nothing will cost $1 trillion in global gross domestic product by 2030, according to McKinsey. But addressing the issue through employer- or publicly-funded child care, for example, or less tangible attitude changes about women’s roles in society, the firm said, could add $5 trillion to $13 trillion to global GDP in the next decade, depending on how aggressive those steps are.

In Central Massachusetts, the MassHire office is helping with job retraining programs and talking with state officials and counterparts in other states about how best to respond to the recession. Some local companies have instituted new flexible hours or remote work policies, neither step of which is costly, said Chelsie Vokes, a labor attorney for the Worcester law firm Bowditch & Dewey. In other cases, employers have begun subsidized child care or more generous paid leave.

“These are all things that employers can implement immediately,” she said.

It is steps like those that give advocates slight optimism the pandemic could force more direct action to improve conditions for working women, or to see remote work or flexible hours aren’t so bad after all.

“COVID comes along and highlights this very issue,” said Nager, the Boston Club president.

Her hope, she said, is the issue doesn’t fade away once the pandemic does, as can happen with other temporarily important matters.

“This is such a core issue,” Nager said, “and we haven’t dealt with it, really ever.”