The saga over the proposed closure of the Leominster maternity center is part of a national struggle beset by doctor shortages, rising maternal morbidity, and money-losing operations.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

For five years, UMass Memorial Health has attempted to grow the obstetrical practice that, until now, has provided prenatal care and labor and delivery services to women in North Central Massachusetts, said Dr. Eric Dickson, president and CEO of the region’s largest healthcare system, based in Worcester.

“It was never a program that was rock solid,” Dickson said.

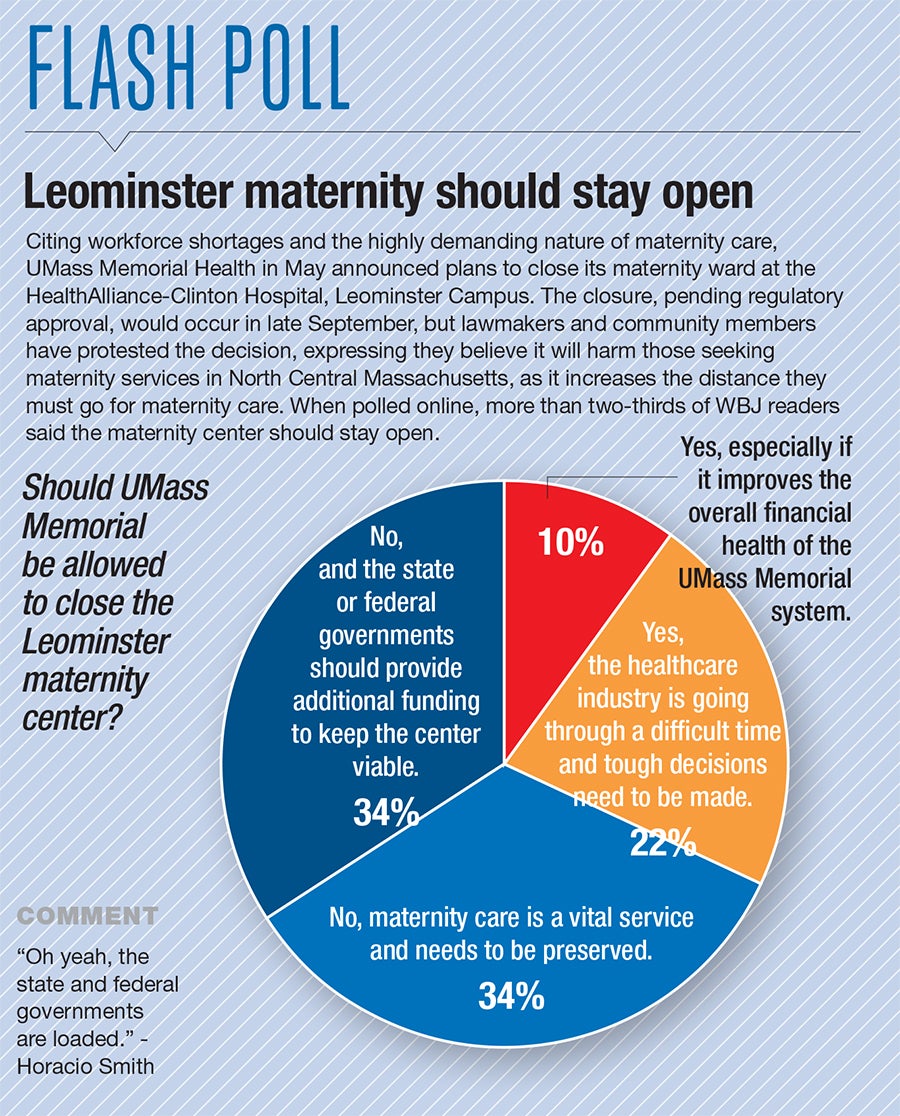

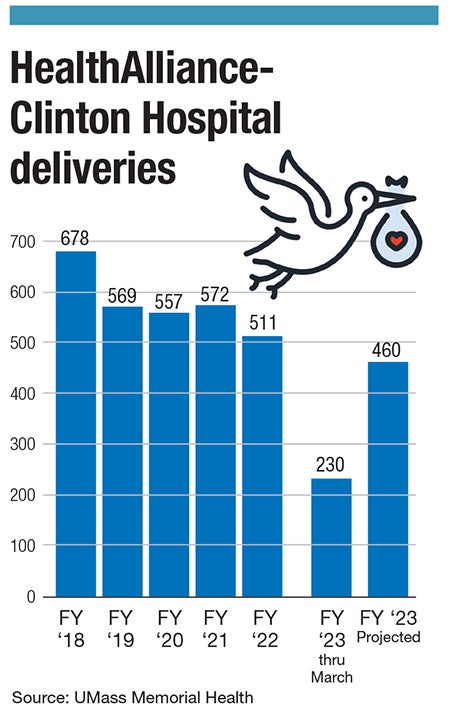

Dickson said the goal was to invest in the program and grow it to a more viable 1,000 deliveries per year at UMass Memorial HealthAlliance-Clinton Hospital in Leominster, but the number of babies born in the city went down and not up, lately hovering around 500, which translates to an average of 1.5 births per day.

That may be due in part to a national downward trend in births during the COVID-19 pandemic, though the trend preceded 2020. Now, the region’s largest healthcare system is turning in another direction to provide care to pregnant women now treated in Leominster: Providing some outpatient OB-GYN care in Leominster but sending women in labor to UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester to deliver.

On May 30, UMass Memorial officials announced the planned closure of the HealthAlliance labor and delivery unit, pending a public comment period and review by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. It’s unusual for DPH to stop a hospital from closing a program, but DPH deemed the unit an essential service on Aug. 9 and is requiring UMass Memorial to provide detailed plans about how it will assure access to inpatient maternity care to patients in the region by Aug. 23.

DPH’s ruling is stronger than others when hospitals announce plans to close services, amounting to a grilling of UMass Memorial, said David Schildmeier, spokesman for the Massachusetts Nurses Association labor union.

“It’s really clear that they have concerns,” Schildmeier said.

But to Dickson and other leaders at UMass Memorial, including Dr. Tiffany Moore Simas, chair of obstetrics and gynecology for the system, the planned change marks an improvement in care for women in North Central Massachusetts. Simas was the first to raise a concern about the safety of labor and delivery at HealthAlliance, Dickson said. There is just one OB-GYN left on staff, and another works on a contract basis, along with a midwife at the hospital.

The capabilities of the Worcester labor and delivery unit far exceed those offered at a small community hospital like HealthAlliance, Dickson said. For example, if someone arrives in the middle of the night for an emergency Cesarean section, often a doctor has to be called to come in to work, something larger hospitals don’t contend with. The Leominster hospital has no neonatal intensive care unit.

The capacity in Worcester is greater because the maternity unit was built at a time when birth rates were higher, Dickson said.

Meanwhile, a large coalition of local and state elected officials and other stakeholders aren’t buying it.

Emotions ran high during a lengthy hearing in July, during which some people angrily called out Dickson and other hospital officials, saying low-income and patients of color will be hurt the most by the decision to relocate labor and delivery care 30 or more minutes south of Leominster.

Underscoring their point was a scathing report by DPH on July 12, detailing a large increase in severe maternal morbidity – essentially, life-threatening events for mothers giving birth – in the last 10 years in Massachusetts. This speaks to a national trend toward worsening outcomes in childbearing in the U.S., which is considered by many to be a scandal in a country that spends the most money on health care and boasts the best medical technology in the world.

Nationally, as here in Massachusetts, Black and Latino mothers are those who face the highest risk of severe maternal morbidity. Irene Hernandez, a resident and healthcare professional who co-chairs the coalition opposing the Leominster unit closure, said her own daughter had been otherwise healthy when, at 25, she nearly died giving birth due to a complication causing severe bleeding. Had she not made it to HealthAlliance for an emergency C-section, Hernandez said her daughter and grandson would have died.

Hernandez now worries about low-income mothers who don’t have reliable transit to travel to Worcester for hospital care and suspects UMass Memorial is shifting away from such patients for financial reasons.

“When low-income people have babies, the compensation rate from MassHealth [the state’s Medicaid program] just breaks even,” she said.

A risky business

Dickson, though, insisted the decision to close labor and delivery at HealthAlliance-Clinton was chiefly clinical.

At issue, he said, is hiring enough doctors to safely staff the unit. Obstetricians are often hesitant to deliver in a small community hospital, preferring larger hospitals with specialist care around the clock to handle emergencies and more complicated cases. For that reason, it’s been a struggle to build out the OB-GYN practice in Leominster. Related to this, Dickson said, is the fact the risk of medical malpractice suits for obstetricians is higher than other specialties.

“It’s a risky business. One delivery goes wrong, one bad outcome, is a big problem for an obstetrician,” Dickson said.

HealthAlliance-Clinton is hardly an outlier. Elsewhere in Massachusetts and across the country, the number of hospitals delivering babies has fallen, adding to a phenomenon known as maternity deserts, defined by the nonprofit March of Dimes as U.S. counties without access to labor and delivery care. No region of Massachusetts is classified as a maternity desert, and the March of Dimes calls it a full-access state, given every county has two or more hospitals offering services, or 60+ providers per 10,000 births.

Yet, 10 hospitals have closed their labor and delivery units since 2010. In Central Massachusetts, those include the former Baystate Mary Lane Hospital in Ware and UMass Memorial Harrington Hospital in Southbridge. Central Massachusetts is still home to six other hospitals, including UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester and Saint Vincent Hospitals in Worcester, with labor and delivery services.

Nationally, at least 89 hospitals closed obstetric units between 2015 and 2019, and almost half of rural hospitals didn’t offer obstetric services, according to the American Hospital Association.

Operating at a $4M loss

Despite Dickson’s insistence the closure is not about money, Medicaid payments, which are about one third the rates paid by commercial insurers for hospital births, are an underlying factor putting pressure on the bottom line.

HealthAlliance-Clinton is among Massachusetts hospitals with a high public payer mix, meaning a majority of patients are insured by Medicaid. Such populations may not support the kind of investment in obstetrical programs hospitals in more affluent areas do.

Labor and delivery services at HealthAlliance-Clinton aren’t solvent, Dickson said. The unit finished fiscal 2022 with a $3.74-million operating loss. But he said by redirecting the care of those patients to Worcester, the system is simply moving a money-losing book of business from one hospital to another.

Cost pressures on healthcare systems are forcing difficult decisions, and Medicaid-heavy programs, such as maternity care, will take a hit, Dickson said. “Change, or you’re going to fail,” he said.

Tenet reverses Framingham shortage

Another area hospital that’s struggled with staffing its labor and delivery unit is Metrowest Medical Center in Framingham. The Tenet Healthcare-owned sister of Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester faced a registered nurse shortage late last year, said Dr. Michele Sinopoli, an OB-GYN who serves as chief medical officer for Saint Vincent and Metrowest Medical Center.

When the workforce isn’t stable, Sinopoli said doctors are hesitant to deliver at a hospital, but Tenet doubled-down on hiring and training new nurses to work in labor and delivery, a specialty traditionally harder for new nurses to break into. Meanwhile, the system hired a group of laborists: doctors who work only in labor and delivery and don’t have to spend any time outside the hospital at outpatient clinics. Together, these have stabilized labor and delivery operations.

Like UMass Memorial, many Metrowest patients are covered by Medicaid and face some of the same issues that Leominster-area mothers do, such as lack of transportation to a Worcester hospital.

“We were very emphatic about that … We have no intention of closing the labor and delivery unit at Metrowest Medical Center. It’s incredibly important to the community, especially those with transportation issues,” Sinopoli said.