Strong economy helped Central Mass. banks, and mergers gave two an extra boost

Photo | Grant Welker

Fidelity Bank's branch on Worcester's Front Street

Photo | Grant Welker

Fidelity Bank's branch on Worcester's Front Street

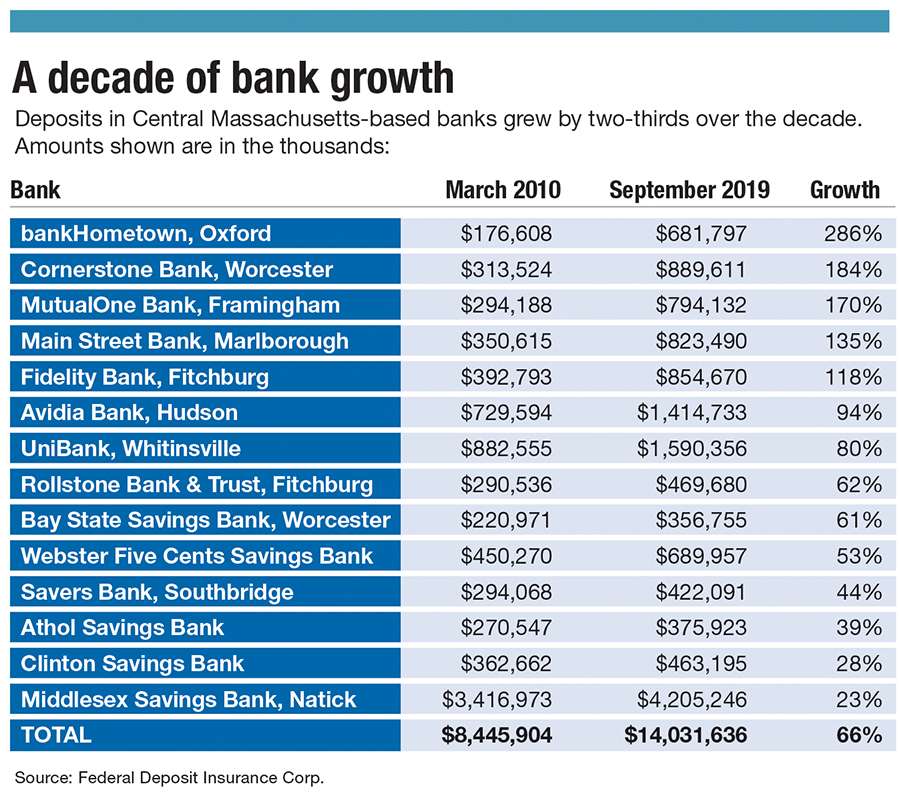

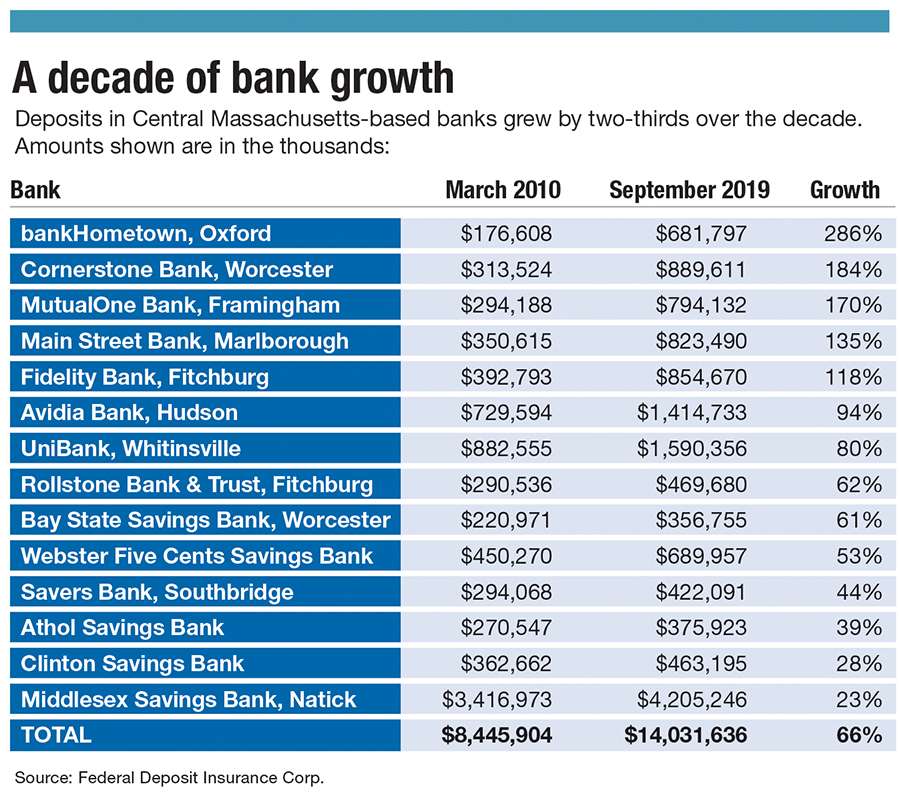

Deposits were way up for the last decade at banks based in Central Massachusetts. The booming economy had a lot to do with it, of course.

Growth was almost all organic except for two banks, which became aggressive through mergers and acquisitions: bankHometown and Fidelity Bank.

Leaders of both banks said they focus primarily on growth through serving their customers in the best way. But when banks find the fit to be right, they said, they’ve made a move to grow through acquisition and take advantage of greater efficiencies.

“The opportunities are few and far between,” said Robert Morton, bankHometown’s president and CEO. “The circumstances and conditions have to be just right.”

bankHometown’s deposits grew more than any other Central Massachusetts-based bank over last decade – nearly tripling – thanks in large part to a few aggressive moves: taking over Athol-Clinton Cooperative Bank in 2011, adding what at the time was a roughly $300-million bank, and Millbury Savings Bank in 2018, with its roughly $185 million in deposits.

bankHometown also took over five Connecticut branches of sister bank Easthampton Savings Bank, which is now known as bankESB and shares the same parent company, Hometown Financial Group, based in Easthampton.

bankHometown, now with 15 locations, is building its first Worcester branch to carry the bankHometown name from its opening, joining a Millbury Savings location, which switched names upon the merger.

Fidelity Bank – whose deposits more than doubled last decade – has been more active than any other Central Massachusetts-based bank, with three acquisitions in a four-year period.

The Leominster bank acquired Barre Savings Bank in 2016, Colonial Co-operative Bank from Gardner in 2018 and Family Federal Savings Bank of Fitchburg in 2019. That comes after a period in which the bank had only three other mergers since the 1970s.

It’s not as if Fidelity Bank wasn’t previously having discussions with other banks about potential marriages, said Edward Manzi, Fidelity’s CEO since 1997. Some potential mergers were abandoned because they didn’t feel like the right fit, he said.

Quiet on M&A front

Most Central Massachusetts banks weren’t active with mergers and acquisitions over the decade.

The largest Central Massachusetts-based bank, Middlesex Savings Bank of Natick, hasn’t acquired or merged with a competitor since 2009 when it took over Strata Bank of Medway. For Avidia Bank, the region’s third-largest by deposits, it’s been since 2007, when Avidia was formed with the merger of Hudson Savings Bank and Westborough Bank.

A share of mergers have been among similar-sized entities – like at Avidia, or with Marlborough Savings Bank and North Middlesex Savings Bank merging in 2017 to form Main Street Bank.

A few notable transactions involve a Central Massachusetts bank being folded into another. Worcester-based Commerce Bank became part of Berkshire Bank in 2017.

Berkshire kept the Commerce Bank name on 13 Central Massachusetts locations, but Berkshire’s name has otherwise been spreading seemingly everywhere, with the bank moving its headquarters from Pittsfield to Boston, and acquiring Savings Institute Bank & Trust of Connecticut in 2019, its ninth merger of the decade.

Milford National Bank was acquired in 2018 by another bank that’s been quickly growing through mergers: Rockland Trust. Rockland, which is building its first full-service Worcester branch, made eight acquisitions over the decade, largely south of Boston.

Consolidations expected to continue

A few generations ago, practically each town would have its own savings bank, giving a local flavor to each institution, said George Tetler, a lawyer with the Worcester law firm Bowditch & Dewey, who works with area banks on merger and acquisition issues.

“Each town appreciated having its own bank. There was a sense of pride about it,” Tetler said.

Nationally, the result of decades of mergers and acquisitions is clear. The Federal Deposit Insurance Commission counted more than 12,000 banks in 1990. By 2017, the number dropped below 5,000 for the first time.

The smallest banks have been disproportionately hit.

In Massachusetts, the number of banks with assets of under $100 million has shrunk from 96 to six, said Daniel Forte, the president and CEO of the Massachusetts Bankers Association. While much of that can be attributed to banks growing out of the smallest segment, it’s also largely because those are the banks that have been scooped up by larger competitors, he said.

Going back to 1960, Massachusetts has almost a third of its banks, Forte said. He expects the trend to continue. Banks are pressed to create economies of scale to help with regulatory requirements or investing in new technologies, he said.

“Much like other mature industries, consolidation has always been there and is going to continue,” Forte said.

Even still, the decision is largely up to the banks themselves, Tetler said.

That’s because nearly every bank in Central Massachusetts is a mutual bank, meaning its decisions are driven by depositors and their directors – not like at a trust, like Berkshire Bank or Rockland Trust, where shareholders may be more driven by bottom-line considerations.

“That’s a very big distinction,” he said.

0 Comments