The modern Massachusetts economy has been growing for 400 years, since settlers first landed in Plymouth in 1620. And for 245 of those 400 years – more than 60% – the Massachusetts economy was tied to the legal institution of slavery.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The modern Massachusetts economy has been growing for 400 years, since settlers first landed in Plymouth in 1620.

And for 245 of those 400 years – more than 60% – the Massachusetts economy was tied to the legal institution of slavery, first as Massachusetts legalized and profited from slavery. Then, after Massachusetts abolished the practice, businesses still benefited right up through the Civil War from the use of free labor in the American South, particularly surrounding the proliferation of slave-grown cotton and its use by mills in the Blackstone Valley.

“What we don’t realize is the extent to which those choices that manufacturers made and consumers made affected slavery,” said Calvin Schermerhorn, a slavery historian at Arizona State University. “It wasn’t just a Southern phenomenon. It was an American phenomenon.”

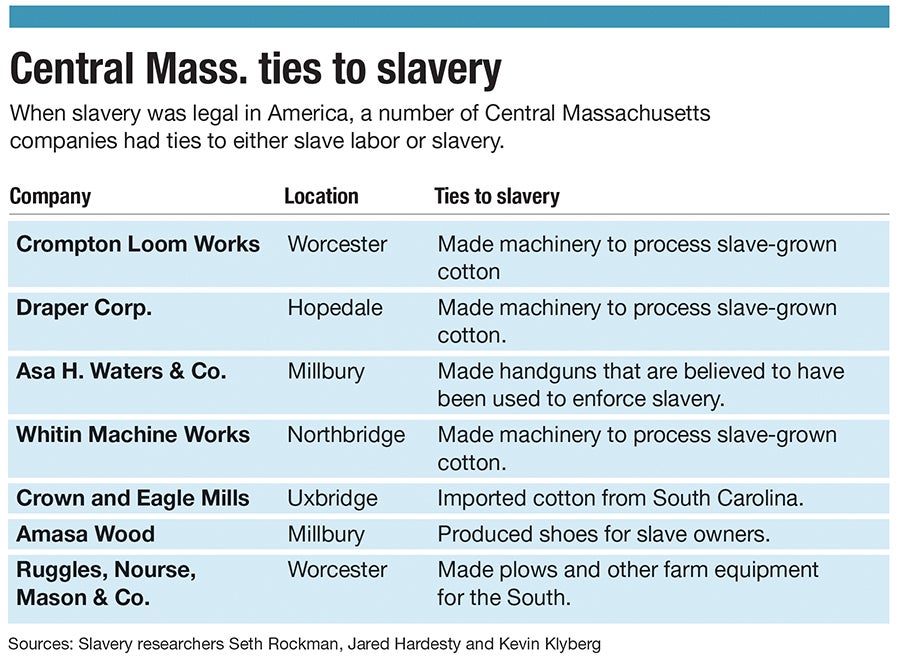

While the direct legacy of Central Massachusetts’ ties to slavery lingers mostly in the names of now-closed prominent businesses with those ties – Crompton, Draper, Whitinsville, Asa Waters – the enduring legacy can be seen in the renewed efforts this year surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement, the fallout from the police killing of George Floyd, and companies seeking to update their diversity & inclusion programs, as the generational consequences of slavery and the oppression of freed enslaved people and their descendants after the Civil War still impact the economic mobility of Black people in America.

“In some ways, anyone who bought a cotton shirt for 200 years in the United States played some sort of part,” said Kevin Klyberg, park ranger at the Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park, in Worcester.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War when the American economy expanded around the textile industry, Central Massachusetts didn’t necessarily benefit from the institution of slavery any more or less than other areas of the country where slavery was abolished, but the region’s ties illustrate how foundational slavery was to the entire nation’s prosperity and how the beneficiaries of the practice were far more than a handful of slave owners. Even as Massachusetts was one of the first states to abolish slavery and Central Massachusetts played some key roles in the abolitionist movement, businesses in the region helped process the raw materials produced by enslaved people in the South and in turn sold finished goods to the South to be used by enslaved people and their owners.

“One of the striking things about the industrial history of the Blackstone Valley was how infrequently abolitionists connected the region’s prosperity to slave-grown cotton and Southern markets for manufactured plantation provisions,” wrote Seth Rockman, an historian at Brown University in Providence, in a history book chapter “Slavery and Abolition along the Blackstone.”

Even though slavery was abolished throughout America in 1865, the lingering effects of the practice has led to Black people struggling to gain equal economic and societal opportunity ever since, right up through the 21st century, wrote Ronald Waters, the director of the African American Leadership Institute at the University of Maryland, in an article for the “Journal of African American History” published posthumously in 2012.

“Whites enjoyed a monumental head start as slaveholders and the creators of a society built on the wealth the enslaved workers produced,” Waters wrote. “Thus, whites were the arbiters of African Americans’ entrance into that society.”

Among those lingering effects today, in Worcester County, less than 1% of all businesses are Black-owned, despite Black people comprising 6% of the county’s population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Those Black-owned businesses on average have fewer employees and smaller payrolls than the average for all Worcester County businesses.

In a 2019 survey of Americans, the Pew Research Center in Washington, D.C. found most people – 63% – believe slavery still impacts the position of Black people in American society a great deal or a fair amount. Among Black Americans, the rate was 84%, compared to 58% among white respondents.

Slavery in Massachusetts

Slavery existed in Massachusetts from the earliest Colonial days. Enslaved people were first brought by boat in 1638 into Boston, and Massachusetts was the first colony to legalize slavery in 1641, according to the Massachusetts Historical Society. Between 1755 and 1764, enslaved people made up 2.2% of the Massachusetts population, concentrated in industrial and coastal communities, according to the history of the abolitionist movement from the Massachusetts state government.

“New Englanders essentially crafted a narrative where when they do acknowledge slavery at all, they make slavery something … that played a minor role economically,” said Jared Hardesty, associate professor of history at Western Washington University and author of “Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston.”

“In the entire business economy of Massachusetts in Colonial times and after the Revolution … slavery is a significant component of it,” Hardesty said in an interview with WBJ.

Colonies in New England exported salt, cod, timber, livestock, corn or rum to either feed enslaved people or to communities benefiting from their work, particularly in the West Indies. Smuggling, shipping and slave trading helped the regional economy even without having enslaved people living locally, said Kirt von Daacke, assistant dean and an associate professor of history at the University of Virginia.

“Even if a town had few enslaved people, that didn’t mean that slavery and the wealth that the slave trade and slavery-related business produced didn’t directly impact economic development in places such as Worcester,” he said.

Slavery was legal in Massachusetts until 1783, among the first states to embrace abolition. Worcester County played a key role in that process through a slave vs. owner case initially tried in the Worcester County Court of Common Pleas.

Quock Walker, who was born into slavery as the property of a Barre family, filed a series of lawsuits as a young adult, starting with assault and battery against the man who married his original owner’s widow, according to a state website detailing the Massachusetts constitution and abolition. In time, one slave owner sued another for interfering with his property, and the state Supreme Judicial Court got involved. Ultimately, the court’s chief justice in 1783 ruled slavery was incompatible with the state constitution’s principles of liberty and legal equality.

After abolition in Massachusetts, Worcester County was a leader in Massachusetts during a rising antislavery movement in the 1840s, Rockman said, giving the highest levels of support statewide to the Liberty Party, a supporter of the abolitionist movement, and to the Free Soil movement, which tried protecting Western lands from becoming slave states. Blackstone Valley voters also helped drive an antislavery coalition to power in the state legislature.

Worcester’s mayor in the 1850s, Peter Bacon, refused to allow Worcester police officers to assist anyone recapturing a presumed runaway slave, said Rockman. That went against the Fugitive Slave Act, a federal law requiring enslaved people be returned to their owners, even if they were in a free state.

But the economic relationship between the Massachusetts and slavery continued during this time; it had just shifted from the West Indies to the American South, Hardesty said.

“Domestic cotton is going to be sent to New England,” Klyberg said, “and so while the Blackstone Valley is known for having progressive thinkers and ardent abolitionists, you also have this massive industry which at its base is involved in slave-grown cotton.”

Slave-grown cotton & the Blackstone Valley

Successful textile mills and large manufacturing plants were a large part of the American Industrial Revolution. In fact, Westborough-born Eli Whitney is credited with inventing the cotton gin in 1793, making the process of separating cotton from seeds far faster than before.

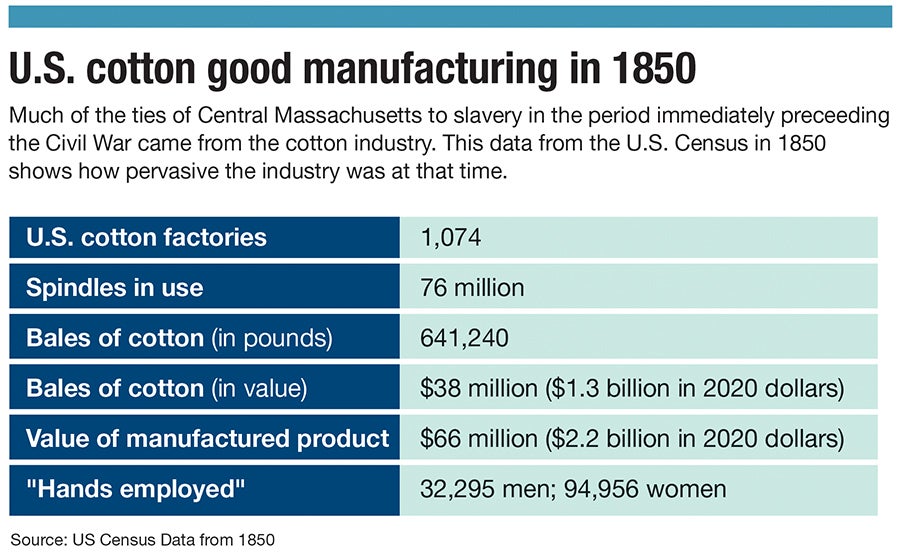

With that breakthrough, the textile industry boomed. Mills became prominent not just in the Blackstone Valley but in cities from Holyoke to Fall River to Lawrence. Many Massachusetts’ towns began as mill towns along rivers, Klyberg said.

Mill owners often had direct connections to slavery and slaveholding, Hardesty said, as they depended on buying cotton from the South grown by enslaved people.

The Crown and Eagle Mills in Uxbridge, for example, imported nearly 240,000 pounds of cotton from South Carolina each year, while the Douglas Manufacturing Co. obtained nearly an identical amount from Georgia, Rockman wrote.

The abundance of cotton and rise of textile mills came together to create a strong textiles industry that furthered the demand for cotton. While those mills became successful because of the cost advantages of slave-grown cotton, manufacturing plants in the Blackstone Valley supplied them with machinery.

Whitin Machine Works – whose owners’ family gave Whitinsville its name – made machinery used to prepare slave-grown cotton for manufacturing.

The Draper Corp. manufactured looms for textile factories before slavery was abolished. It then sold looms to cotton mills that were, in turn, buying slave-grown cotton to use on Draper’s looms.

“You might think of yourself as a machine maker that has nothing to do with that process, and yet, of course if your machines are processing cotton, then you are,” said Klyberg.

The Draper Corp. – whose roughly 1-million-square-foot mill still towers over the center of Hopedale – was at one point the largest maker of power looms in the country and operated for more than 130 years.

What would become Crompton Loom Works of Worcester was started by William Crompton, a British immigrant who received a U.S. patent in 1837 for his new loom allowing for fancier clothing, more patterns and was easier to use.

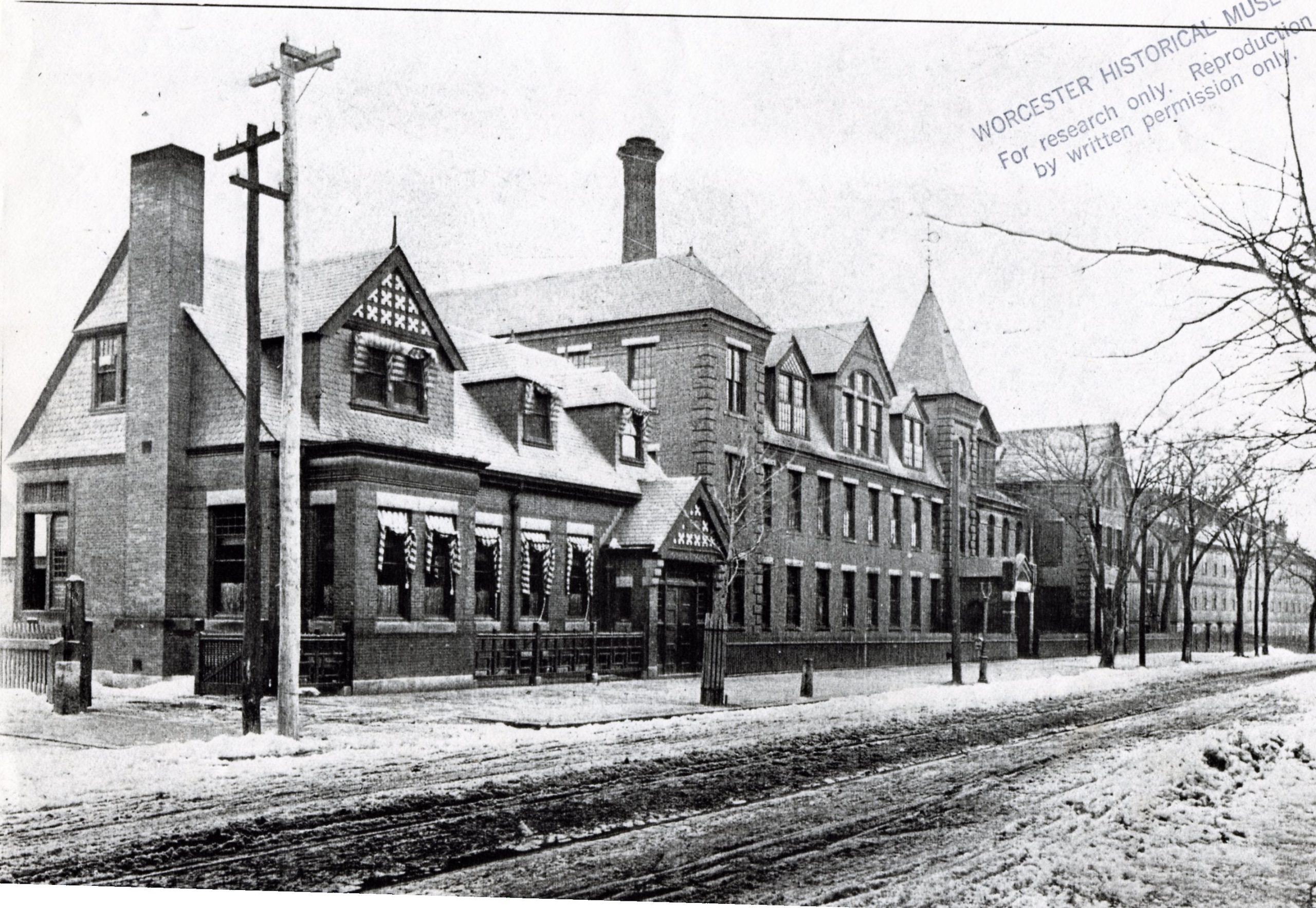

Crompton’s loom business began then, profiting off of the success of textile mills and the high demand for textiles. His son, George, took the business from his father when his father retired. George Crompton then perfected and popularized the Crompton loom. He established Crompton Loom Works in Worcester in 1860, five years before the abolition of slavery. The building still stands today on Green Street, hosting a mix of commercial businesses.

“It is an abstraction … but it still rests on slave labor,” Hardesty said. “What’s driving the demand for those machines in cotton mills? The access to cheap cotton. And how is that cheap cotton produced? Slave labor.”

The growth of the textiles industry benefited others, too. Looms needed materials like wood and brass, growing to a large network those who profited off of slave-grown cotton, said Joanne Pope Melish, an associate professor emerita in the history department at the University of Kentucky and author of “Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation.”

“Everyone in one way or another is supporting and feeding off of, or making a lot of money, off the textile industry,” Melish said.

The Central Massachusetts’ ties to slavery went beyond the textile industry, as slavery affected every part of the economy, Hardesty said.

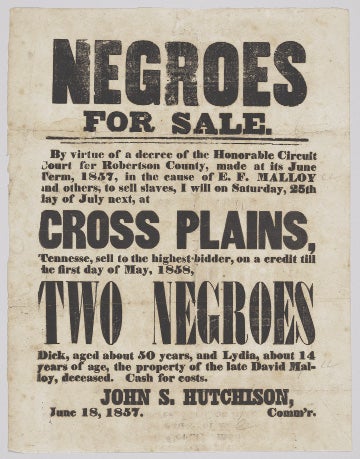

Shoemakers in Leicester produced footwear for enslaved people and one in North Brookfield was one of the state’s largest such shoemakers, while another in Millbury made fancier versions for the slave owners. A Worcester hatmaker produced 7,000 palm-leaf hats each year to be sold in Southern markets, and a plow maker designed machines specifically to be used for enslaved people.

“Especially adapted to slaves,” Ruggles, Nourse, Mason & Co., the plow firm, said in an advertisement of its tools in the mid-1800s.

Millbury gunmaker Asa Waters & Co. – whose industrialist founder built the Asa Waters Mansion in Millbury – had a significant market in the South, where firearms were used in the policing of runaway enslaved people and suppressing slave uprisings, wrote Rockman.

“The South is both a market and a producer for New England,” Melish said.

Slavery’s impact on today’s diversity & inclusion efforts

In his 2012 article “The Impact of Slavery on 20th- and 21st-Century Black Progress,” Waters, the professor from the University of Maryland, called the idea of slavery ending in 1865 a devastating myth. Several institutions following abolition still perpetuated the remnants of slavery, such as when sharecropping was used to keep the price of cotton cheap, he wrote.

Beyond those institutions, Waters – citing sociologist Joe Feagin from Texas A&M University – wrote several lasting conditions from slavery continued to supress the economy and cultural mobility of Black people in America into the 20th and 21st centuries, specifically:

• Restrictions on Black voting in many areas of the South;

• Black children still attending segregated schools;

• Black families living in segregated areas;

• Black people facing informal discrimination when seeking housing;

• Black defendants being tried for crimes by all-white juries;

• Black professionals facing discrimination in the job market.

“Intergenerational poverty was transferred and carried like invisible baggage from place to place,” Waters wrote. “As African Americans were forced into ghettoized communities in the South and in the North, poverty became a dominant feature.”

This poverty has been carried forward and exacerbated by government policies limiting access of Black people to social programs and through the persistent effect of Southern cultural values on American society at large, Waters wrote.

“For Americans to acquire more cosmopolitan attitudes and values that support social justice for all, free of a racial animus, would require change in the interpretations and understanding of U.S. history and dominant cultural values,” he wrote.

Such efforts to find a better understanding of the Black experience in America have been at the core of the greater emphasis on diversity and inclusion since the police killing of George Floyd in Minnesota at the end of May.

Those moves include executives at UMass Memorial Health Care in Worcester, the region’s largest employer, taking part in a Black Lives Matter rally put on by one of its medical professionals; the College of the Holy Cross and Worcester State University examining their policies to entice more diverse staff and students; and the Hanover Insurance Group in Worcester increasing its efforts to have inclusion be part of its core culture.

“The racial equality issues and the unrest today is a problem for society and our business, especially if we don’t step up and help some of the systemic issues of our society go away,” Hanover CEO Jack Roche said in an interview for WBJ’s Executive to Executive feature in August. “We are going to do more than say nice things. We are going to change the way we recruit into the community and change the folks we engage with in order to address these issues.”

WBJ News Editor Grant Welker contributed to this report.