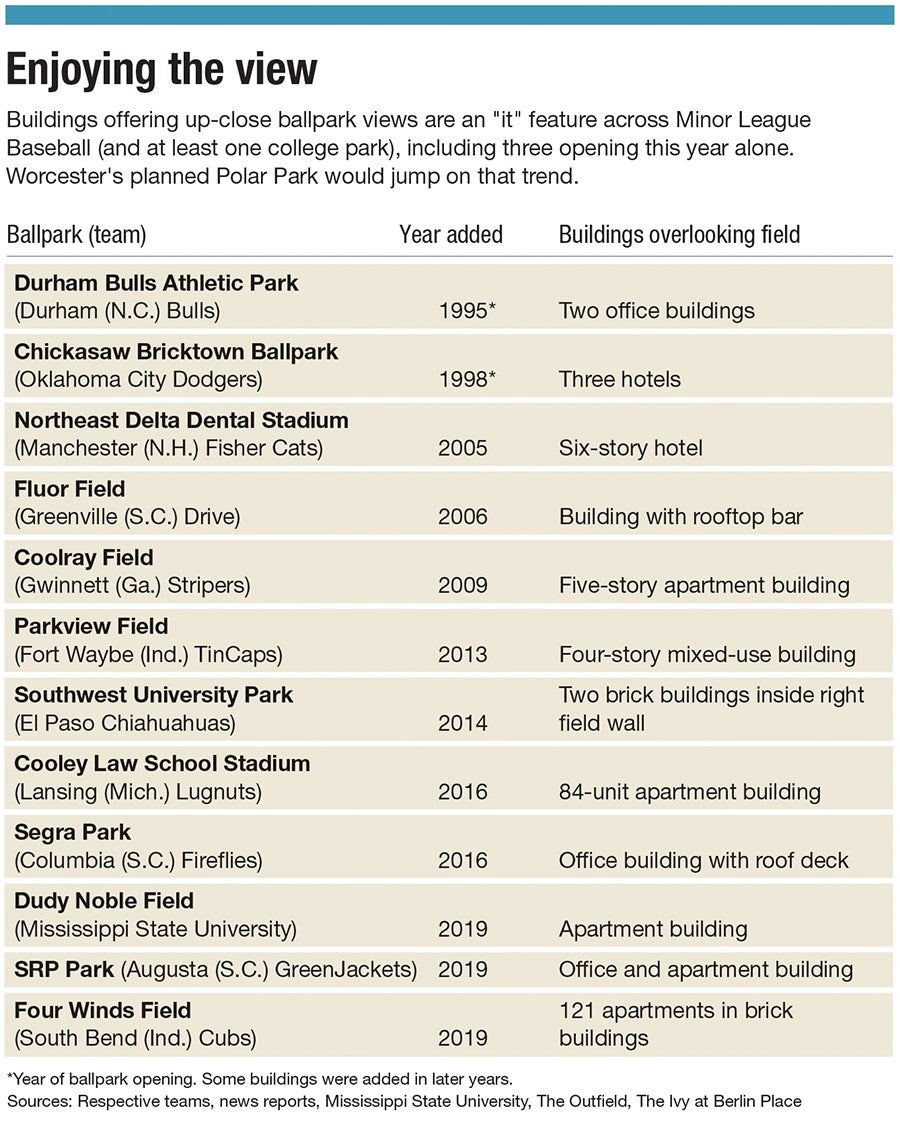

Worcester’s planned Polar Park touts ballpark views from a brick building standing just beyond left field.

Such a building, a central component of still-in-the-works designs for $101-million Polar Park, would certainly stand out at the spartan McCoy Stadium, the longtime home of the Pawtucket Red Sox, who plan to move to Worcester in 2021.

McCoy Stadium, which opened in 1942, has virtually no features that would land it on a must-see list for baseball fans.

A renovation two decades ago added a grassy outfield berm, but even that feature isn’t enough to keep up with ballparks today with amenities fans would normally expect to see in top-level Major League Baseball, including luxury boxes and plush oversized seating. Diversions taking fans’ eyes off the game action are more commonplace, from bars and fire pits to table games and swimming pools.

As Worcester and PawSox officials begin to finalize architecture and construction plans for the fourth most expensive minor league ballpark ever constructed, they are entering an arms race in stadium design meant to entice people to buy tickets to an experience much more elaborate than simply watching a baseball game.

[Related: Polar Park has 21 months to avoid typical cost & delay issues in stadium construction]

Kevin Reichard, the publisher of the website Ballpark Digest, calls each area something like a neighborhood appealing to different fans: fixed seats for die-hards, suites for entertaining and corporate gatherings, pools and a bar for families, and casual seating areas for younger adults.

“That model seems to be the case for any new facility out there,” Reichard said. “People don’t sit in their seats for the whole game anymore.”

Adding costly features

Until around two decades ago, minor league ballparks were much more utilitarian. The parks were cheap to build and the games affordable to attend.

But that’s sharply changed, especially in the past decade, in what can feel like a competition of who can spend the most money for stadium amenities.

Rafi Kohan, the author of the book “The Arena”, which explores the evolution of stadiums and fan experiences, said teams are paying far more attention to drawing fans to the game – even if it’s for reasons other than the game itself.

Kohan said new amenities might be little more than ways to draw more revenue out of fans.

“This sort of community versus corporate feel is evident at many new stadiums, and I think owners need to tread lightly, lest they destroy that special thing that has always kept fans coming to games: a sense of communion,” he said.

Jonathan Emmett, a principal and design director for the sports architecture firm Gensler, told the industry magazine Stadia this spring stadium designs today are designed for hospitality and social experiences.

“No matter what sport,” he said, “venues are increasingly focused on hospitality and enhancing the fan experience.”

As the list of features have risen, so have price tags, corresponding to ever-larger public contributions, leaving teams to no longer having to worry about new parks being economically feasible. Worcester is covering roughly $65 million of the cost of Polar Park.

“Another aspect of the minor league ballpark revolution, specifically, is surely a trickle-down effect of the public subsidy craze for pro facilities,” Kohan said.

Rail lines & diner cars

As the PawSox and Worcester work with architects to design Polar Park, Worcester’s stadium will have a high bar to reach. The price tag is high, too: $101 million, including buying and knocking down existing buildings on the site. That price makes Polar Park the fourth most expensive minor league park ever built when adjusted for inflation, according to a Worcester Business Journal review of minor league stadiums.

The architecture firm designing Polar Park, Somerville-based DAIQ Architects, has played a role in some iconic stadiums, including modern upgrades to Fenway, the Rose Bowl and Dodger Stadium. Janet Marie Smith, a renowned sports architect who designed Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore and now works for the Los Angeles Dodgers, is consulting on the project.

While the design team finalizes its plan for Polar Park, a master plan last year showed a range of inspirational looks the team was considering largely a brick industrial atomsphere. Initial renderings showed a Fenway Park-like design, right down to a Green Monster and Fenway’s same field dimensions, but planners later said that was unlikely.

Other than the left field brick building, one known feature of Polar Park will be the rail line along the third-base line, similar to an amenity offered at stadiums in Greenville, S.C., Fayetteville, N.C., El Paso, Texas, and Binghamton, N.Y.

Other potential features, WooSox officials have said, could include a diner car beyond center field in an homage to eateries have long dotting Worcester’s landscape.

Ferris wheels, carousels & more

Modern minor league parks have the elaborate brick facades fans once saw only at Fenway Park in Boston or its more modern copycats in Major League Baseball. There are other head-turning features, too.

In Davenport, Iowa, an 110-foot Ferris wheel sits beyond left field, near bumper cars, a carousel and – because it’s Iowa – a mini cornfield. Nashville’s three-year-old ballpark has a mini-golf course and a bar with foosball and ping pong tables and shuffleboard.

Isotopes Park in Albuquerque, N.M., has a four-foot-high, 45-degree-angle hill in the field of play leading up to the center field wall, a distant echo of the long-demolished Crosley Field in Cincinnati. A park in Frisco, Texas, added a 174-foot-long outfield swimming pool in 2016, and Las Vegas Ballpark opened this year with its own pool.

These days, traditional grandstand seating takes up a smaller portion of ballparks’ total capacity.

Chukchansi Park in Fresno, Calif., which opened in 2002, removed 1,000 seats for this season to make way for tables where fans can sit and eat without balancing food on their laps. A Fayetteville, N.C., park opened this year with an outfield section of only rocking chairs.

New parks even in the lower levels of the minor leagues have features and costs unlikely a generation or two ago. Two independent league stadiums have opened in the last few years in Minnesota and just outside Chicago that each cost $63 million.

The St. Paul, Minn., park offers space for corporate events and weddings in rooms that wouldn’t look out of place at the headquarters of a tech company.

Reichard, of Ballpark Digest, said the St. Paul Saints had little choice but to build an eye-catching park with unexpected amenities because the team has a lot to compete against in the Twin Cities area, with roughly 3.6 million people and eight other professional teams.

“They had to go upscale to compete,” he said.