When a would-be restaurateur approaches Worcester city officials with a plan to open a new eatery, not so much stands in the way procedurally – at least compared to most Massachusetts cities and towns.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When a would-be restaurateur approaches Worcester city officials with a plan to open a new eatery, not so much stands in the way procedurally – at least compared to most Massachusetts cities and towns.

Worcester and two dozen other communities across the state have no cap on the number of liquor licenses they can approve, an economic development tool public officials say gives a leg up in being able to approve with relative quickness a proposed restaurant, bar or brewery.

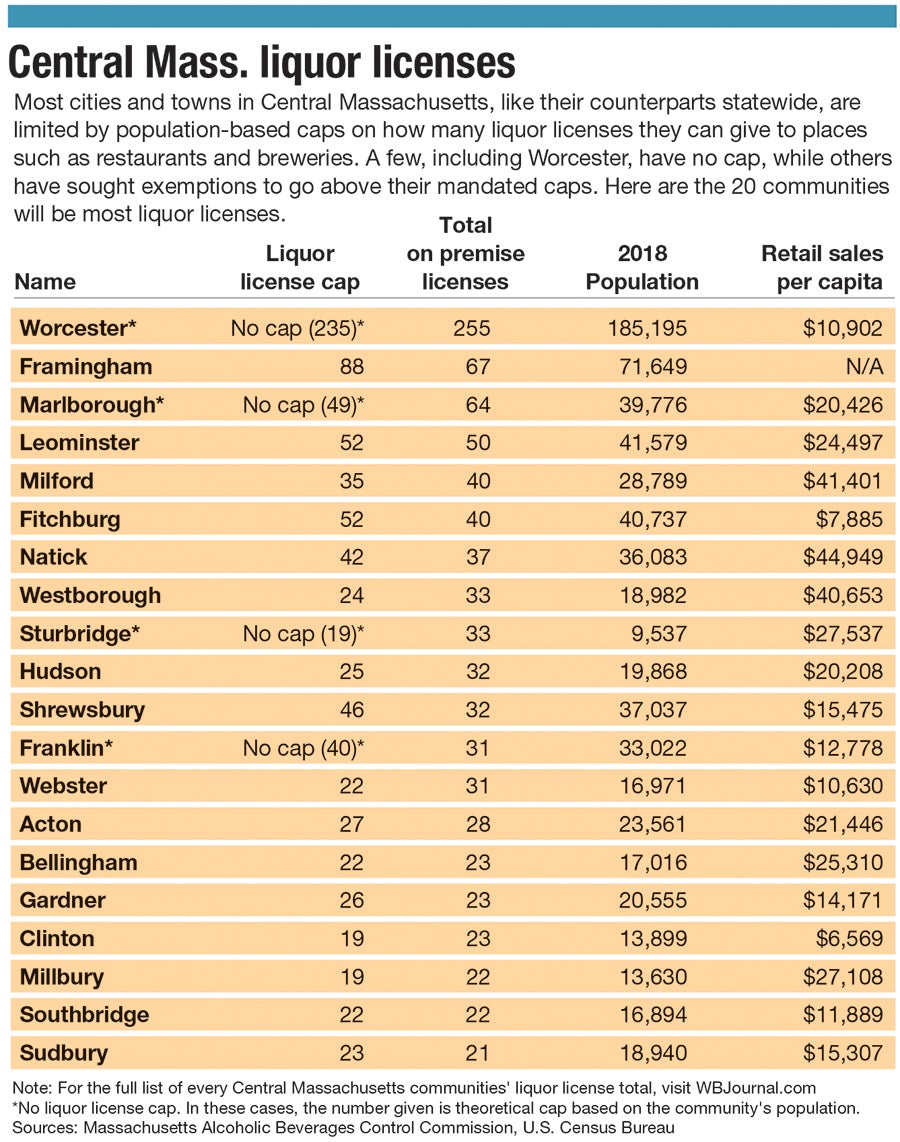

In this 2020 joint reporting project with the Worcester Business Journal and the Worcester Regional Research Bureau, the findings show communities without a liquor license cap for on-site consumption – a list also including Marlborough, Franklin and Sturbridge – often have more establishments than those without one, and in many cases, far more.

Among those 25 statewide communities without a quota, active licenses exceed what those cities and towns would theoretically be capped by 44%. In other words, they’ve taken advantage of the ability to have more restaurants, the related buzz coming from being known as a restaurant destination, and a bigger economic engine attracting people eating and dining in town.

To read the full Worcester Regional Research Bureau report, click here.

“Cities and towns like restaurants because we can’t be internet-ed out of business,” said Bob Luz, the president and CEO of the Westborough-based Massachusetts Restaurant Association. “They want it because it brings a vibrancy to downtowns.”

The great majority of the remaining Massachusetts cities and towns are forced to turn to the state Legislature for special approval if they want to approve more restaurants, bars or breweries, putting them at the mercy of the state’s bureaucracy if they want to make a larger hospitality industry a bigger portion of the local economies.

A huge economic tool

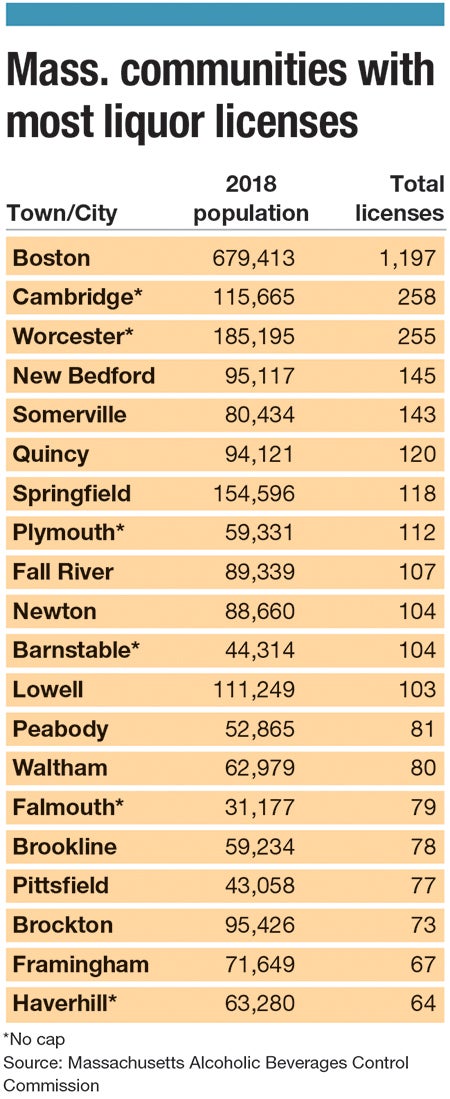

Worcester, which has the third most active liquor licenses in Massachusetts behind Boston and Cambridge, hasn’t had a license cap since the City Council voted to lift the quota in 1983.

“Not having a cap really reduces the scarcity of licenses, so it tends to be cheaper,” said Peter Dunn, Worcester’s chief development officer. “It reduces the barrier to entry, and helps get restaurateurs started.”

The absence of a cap gives businesses two other things they highly value, Dunn said: certainty and time. They can be sure there will be a license available to them, and the process for obtaining a license is as simple as winning approval from the License Commission, a board often meeting twice a month.

In the last decade, the number of active licenses in the city has grown by 5%, totaling more than 200. Worcester’s licenses tend to be newer: 43% have been issued in the past five years, compared to a statewide average of 38%, according to the WBJ/WRRB analysis.

Other Central Massachusetts communities without a cap have found a built-in advantage when hopeful restaurateurs come with plans for a new business.

“The liquor license situation is a huge tool we have,” said Arthur Vigeant, the mayor of Marlborough, which has 64 active licenses – far more than the 49 it would be limited to under the state’s cap.

“We can meet with the Licensing Board and get one immediately instead of having to go to the Legislatures like most other communities need to do,” Vigeant said.

Marlborough city officials have been pushing to bring more restaurants, bars and breweries to downtown, hoping to keep more workers from its big office complexes in the city past the workday. It has gone as far as soliciting brewpubs in 2017 with a marketing campaign and generous incentives: up to $15,000 for rent and up to $10,000 for equipment.

Downtown breweries in Marlborough have had mixed success since, but today two are operating in there today.

“We’re working with every restaurant we can because they’re the drivers right now,” Vigeant said of the business’ ability to attract people to a downtown that can get quiet at night. “They get people out and about.”

Vigeant’s counterparts in other towns see it similarly. Next door in Hudson, Executive Assistant Thomas Moses helped in the town’s request to the Legislature to get five additional licenses it plans to use as part of its burgeoning downtown restaurant scene. A growing number of restaurants brought new visitors to the neighborhood, but also a problem of sorts.

“We ran out of liquor licenses,” Moses said.

Last year, Hudson got approval for live licenses to use downtown, in addition to another five to be used at the Highland Commons retail plaza. Like Marlborough looking to keep workers from, say, Boston Scientific Corp. or TJX Cos. around the community past the workday, so does Hudson with Intel, whose sprawling office building is about a mile and a half from downtown.

In one meeting with officials at the Intel office, Moses said he asked what the town could do to make itself more attractive for company workers. More high-end restaurants, he was told, for employees to grab a bite or a drink after work.

“It makes your downtown sort of like a 6 a.m. to midnight endeavor, instead of the old 9-to-5,” Moses said. “That makes a town buzz.”

Creating a destination

Sturbridge also punches above its weight with its restaurant scene, which benefits from Old Sturbridge Village and the town’s location at the interchange of the Massachusetts Turnpike and I-84. Sturbridge has 33 liquor licenses, compared to the 19 a town of its size would typically have.

“A lot of restaurants enjoy having the opportunity to sell liquor – it’s part of the experience of going out to eat,” said Sturbridge’s town manager, Jeff Bridges.

With tourism taking a hit from the coronavirus pandemic, Sturbridge is working on a marketing campaign to remind people about dining options and what else Sturbridge is open for. The town’s restaurants, including a string of them lining Route 20, have made Sturbridge a dining destination between Worcester, Springfield and Hartford.

“It’s one of those things a restaurateur would look for,” Bridges said of the town’s absence of a liquor license cap. “We don’t lose those opportunities because of the availability of a liquor license.”

Coming later to the game has been Franklin, which similarly benefits from its easy highway access and location between Worcester, Boston and Providence, along with hosting Dean College and large employers. The town has 31 licenses, though it could have 40 based on its population alone – never mind that it has no cap.

“The fact that there’s no cap is something we as a community have traditionally not used to the full potential as an economic development tool,” said Jamie Hellen, Franklin’s town administrator.

Franklin has made some recent strides, with openings in the past year at GlenPharmer Distillery at the former Incontro restaurant and 67 Degrees Brewing in an industrial building on Grove Street. Up next is a planned marketing campaign called Think Franklin First aimed at locals.

“Not having a cap is something we can hopefully use moving forward to make the difference between having someone try out their idea or not try it at all,” Hellen said. “There’s a lot of people that are commuting into town. The trick is to find the connection between 4 and 5 p.m. when people get out of work and 8 o’clock.”

The limits of the state’s cap

The state’s liquor license law considers the range of a community’s population in deciding how many licenses a city or town gets. That’s why, for example, both Royalston, with little over 1,000 residents, and Charlton, with more than 13,000, are both capped at 19 establishments. That formula is based on the decennial U.S. Census, which was last taken in 2010.

Communities regularly seek to go above their cap with requests going before the Legislature’s Committee on Consumer Protection and Professional Licensure. In each two-year session, those requests often number 30 or so, said Rep. David LeBeouf, a member of the committee and a Democrat whose district covers Leicester and part of Worcester.

The committee often says yes, weighing what LeBeouf said is what’s in the best interest of the community, the proposed licensees and existing licensees. Requests for raising the cap are often tied to a particular address or development area, such as Hudson’s Highland Commons.

“When you find a successful business, we want to do what we can to support them,” LeBeouf said. “They’re a critical part of an area.”

Not every Central Massachusetts community comes close to its allotment.

New Braintree, Royalston and Sherborn each have a single active license, according to the state’s Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission. Lancaster, with more than 8,000 residents, has two.

Among Massachusetts cities and towns without a cap, Worcester stands out as having the largest population, by far. The next closest is Cambridge, and most are smaller communities on Cape Cod or the Berkshires, where tourism can bring far greater demand for restaurants than local year-round populations could support.

Limited licenses selling for $455K

Boston is its own case, not only by law but also in terms of how much demand exists for such a finite number of licenses in a growing and prosperous city.

Boston has roughly 1,200 on-premise licenses, but the number has remained virtually unchanged since 1933 – the year prohibition ended – said Eric Kurss, a restaurant consultant and faculty member at Boston University’s School of Hospitality Administration.

“It’s definitely outdated, and there needs to be some kind of change,” Kurss said.

Doyle’s, a bar that lasted more than a century in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood before closing in 2019, perfectly illustrates the sky-high demand for the city’s limited liquor licenses. Doyle’s ended up selling its license for $455,000 to the steakhouse chain Davio’s for a planned location in the Seaport District, according to The Boston Globe.

The Massachusetts Restaurant Association doesn’t advocate for changing the state’s liquor license system in any way. The group is in a potentially hard place: if it pushes to raise caps or abolish them altogether, those restaurateurs who’ve paid six figures for a license did so for something now essentially worthless.

Keeping the buzz in a pandemic

Restaurants, bars and breweries tend to have an outsized importance in a community’s economy: Even though they might not create the economic output of an industry like manufacturing or the high-salaried employment of health care or higher education, they can be a major draw of visitors and potential new residents and businesses when a city is known for a great restaurant scene or an impressive collection of craft breweries.

That’s all been thrown into disarray by the pandemic.

The Massachusetts Restaurant Association estimates almost a quarter of all eateries, from coffee houses to steakhouses, have closed, thanks at least in large part to the state’s strict guidelines on indoor gatherings.

Luz, the head of the association, is not optimistic restaurants will be in a better place any time soon.

“We’re extremely fearful entering winter,” he said. “Especially if there’s no help from the federal government, at the very least a second round of PPP,” he added, referring to the Paycheck Protection Program, which helped keep many small employers afloat.

Kurss is more optimistic. People have been gathering for coffee or beer for hundreds of years, he said – through pandemics and wars.

“I don’t see that stopping,” he said, imagining restaurateurs will find ways of making their business work the same way they have before.

“I don’t know exactly what a new normal will look like. I don’t think anyone does,” Kurss said. “But people will find new ways of finding success.”