The coronavirus pandemic has opened up a new world, one workers aren’t eager to give up.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

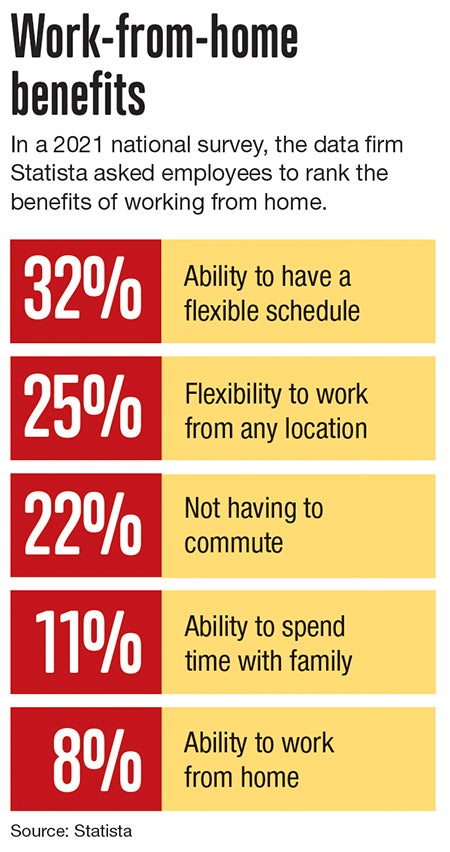

There’s no denying that working from home provides increased flexibility throughout an employee’s workday.

What was once, perhaps, a floor of workers quietly tapping away in cubicles and offices, is now many white-collar workers’ own homes, where they are steps away from switching their laundry, easily accessible to family members and housemates and, generally speaking, likely more comfortable stepping away from their computers to do whatever it is they need to do to keep their personal lives running smoothly. Tasks previously delegated to after 5 p.m. and weekends might be slipped in between phone calls and emails, calls to doctors made without fear of prying coworkers’ listening ears.

While the discourse is split among extroverts who miss the proverbial water cooler and introverts who feel they work better when they aren’t being perceived for 8-hour intervals, the work-from-home phenomenon that rocked the office workplace during the coronavirus pandemic has opened up a new world, one workers aren’t eager to give up.

A study from the staffing firm Robert Half of California, whose results were circulated in April, found one in three employees who are currently working from home because of the pandemic would look for a different job if they were forced to report back to the office full-time. Nearly half – 49% – said they’d prefer a hybrid model allowing them to work away from the office for part of their work time.

“Employers are really kind of forced to be flexible,” said Ryan Foley, a partner at Cunningham and Associates, a Worcester-based business consulting firm.

Focus on productivity

It’s too early to say for certain how certain norms may shift for the working-from-home set, in large part because while it may have become easier for those away from the office to set up and attend telehealth appointments or else call healthcare providers, healthcare systems were overwhelmed throughout much of the last COVID year. Although non-health care workers may have suddenly found they had more time on their hands, healthcare providers definitely did not.

In the meantime, employers are now trying to find a middle-ground between maintaining productivity and maintaining their workforce.

“If organizations aren’t willing to go ahead and look at ways to create flexibility, they’re just going to miss out on the talent pool, because that talent pool is now demanding that this change is permanent,” Foley said.

Navigating the shift back to post-pandemic work life doesn’t need to become a game of will-power between employer and employee, though. It might, instead, help to have a shift of perspective.

According to Cunningham, what he’s seeing is an increased interest in shifting toward project-based work in lieu of strictly hourly-based work, also known as the management-by-objective model.

Combined with implementing systems to track and control progress, Foley said, he’s seeing a lot of success with this type of approach to employee management. Employees get the flexibility they want, and employers are able to make sure work is completed.

“Employees want to come back to work because they’re craving the social aspect of it, but those that don’t and don’t feel comfortable, they still have the ability to interact and perform without disrupting the organizational model,” Foley said.

Navigating the vaccine divide

For workplaces, though, the issue of bringing employees back to the office is a bit more complicated than navigating shifting workforce priorities. Companies – especially larger ones, or those whose workers are client-facing – are struggling to decide what to do with an employee pool containing both those who are and who are not vaccinated against the coronavirus, an issue affecting not only the physical makeup of work spaces but how and when to bring workers back to the office.

Joe Deliso, founder of Blackstone Management and Consulting in Sutton, said while he’s definitely seen a shift toward project-based employment models, the No. 1 problem his clients are facing is how to bring people back in the first place.

“Employees, when they come into the facility, they want to know who’s vaccinated and who isn’t,” Deliso said. “This is a reality. They want to know if the person they’re talking to is vaccinated or not.”

One of his clients, he said, split workers by vaccination status, providing each group their own separate work areas and break and restroom facilities. But the challenge doesn’t always end there.

Other clients, he said, have found they have unvaccinated workers who are using their unvaccinated status as leverage to continue working remotely, noting they do not feel safe working in person but do not have plans to get vaccinated, either.

“But they don’t want to lose the person,” Deliso said, “So this is the dilemma.”

Although he’s seen it happen to a limited degree, most employers are not currently opting to terminate employees who refuse to return in person, Deliso said, explaining management doesn’t want to be forced to draw that type of line.

For those he works with, these are the conversations taking up most of their time -- maintaining a level of coronavirus-induced flexibility isn’t the priority just yet. Rather, it’s a question of how to bring people back to the office at all.