The efforts to turn Central Massachusetts into a life sciences epicenter to rival — or depending who you talk to, complement — Cambridge and Boston have been well underway for decades.

Thanks to developments ranging from the building of new facilities such as Worcester Polytechnic Institute’s (WPI) Gateway Park, to large biopharmaceutical firms like Bristol-Myers Squibb coming to the area, major players in the life sciences industry believe our area is on the right track. But no matter how optimistic champions of the region are, it still has a ways to go to reach the level of notoriety and success that eastern areas can claim.

The Summer 2012 Life Sciences Outlook study by Jones Lang LaSalle recognizes Cambridge as a “mature” market, and the Greater Boston suburbs, the Seaport District and Longwood Medical and Academic Area as “emerging clusters.” It identified a “rent ring,” with East Cambridge as its center, with more than 7 million square feet of lab space within 1.5 miles of Kendall Square, and called it “extremely competitive” with rents as high as $65 per square foot. The study cited Bedford, Lexington, Waltham and Medford as communities that will house the next wave of industry success. Central Massachusetts was left out.

All this information and the region’s eagerness to succeed within the life sciences industry beg the question: What can be done to help Central Massachusetts reach its full potential?

Those at the forefront of the industry recognize what they believe are five keys to pushing the industry further.

1. Funding

Easily the biggest issue many see holding back growth is a lack of funding.

“The assets that we have are some great universities, the medical school, WPI, etc.,” said Terence R. Flotte, dean of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. “The limiting factor that I see right now is capital investment. It’s a nationwide issue … but I think also the venture capital tends to be focused around locations that are viewed as hubs, like Cambridge.”

Flotte said Central Massachusetts is close enough to Boston’s venture capital firms that some money flows into the area, but he suggested that government incentives for investments in startups could help.

“If there was more money pumping into the industry, you could get more things progressing. You could sort of throw more stuff against the wall to see what would stick,” he said.

David Easson, director of WPI’s Bioengineering Institute and Life Sciences & Bioengineering Center, said that even though incubators help companies grow without spending what they would without that support, startups need money to get there.

“There is a kind of missing step that (is needed) in order to translate something from an academic lab to a commercial lab,” he said. “There are a number of support mechanisms from our business school, as well, to help startup companies. I think a lot of the pieces are here, it’s really the funding (that) I think could make that transition, really, to the next step.”

2. Partnerships

Those support mechanisms Easson refers to involve collaborations between schools and life sciences companies, big or small.

“That synergy … is very strong,” he said.

Matthew Vincent, director of business development for Advanced Cell Technology in Marlborough, said a revolution in medicine is underway in the area through the development of stem cell therapies, artificial tissues and drugs that slow the impacts of aging.

“With the wonderful schools in Central Massachusetts, UMass Medical Center and a critical mass of academic and company research and development underway here, this part of the state is poised to be able to capitalize on the wave of new innovation and companies in the regenerative medicine space,” he wrote in an email. “That should attract bigger companies to establish a local presence … Nurturing what we have here, and fanning the flames by actively promoting local academic-commercial collaborations … and furthering the involvement of UMass Medical School in clinical trial programs can be a wonderful way to help this region grow.”

3. Training In Biomanufacturing

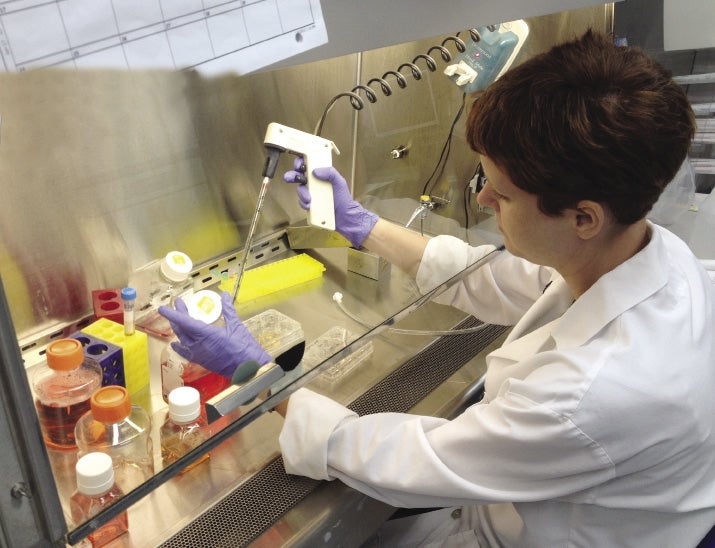

Through the commercial-academic partnerships, WPI found a need for biomanufacturing that the school could help fill. After holding seminars in biomanufacturing fundamentals over the past five years, WPI made a major investment in the field with a Biomanufacturing Education and Training Center (BETC), slated to open in the fall.

“When we saw how successful that program could be, we said, ‘If a fundamentals program could be that successful, what other needs are there?’ ” said Stephen Flavin, vice president for academic and corporate development. The fundamentals training was launched in collaboration with Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Shire Pharmaceuticals (which has a location in Lexington), which Flavin said acknowledged a need for skilled biomanufacturing workers.

“When you’re thinking about maybe bringing on a new drug or manufacturing a new biotherapeutic, you need to be thinking in terms of, ‘Do we have the right population, the right employee skill set?’ ” Flavin said. “We’ll have everything in the facility that you’ll need.”

4. Infrastructure

The BETC is one example of growing infrastructure that many say are imperative to the continued growth of life sciences. Another is the $400-million Albert Sherman Center at UMass Medical School, which will house several programs, including stem cell research, RNA therapeutics and gene therapy.

Vincent noted a need for a network of sorts that would allow expensive, critical equipment and tools to be rented on an as-needed basis, especially for startups that can’t pay for their own equipment.

“Money spent on the equipment is money not being spent to hire additional scientists or skimping elsewhere in a way that reduces the chances of success,” he said.

Kevin O’Sullivan, president and CEO of incubator Massachusetts Biomedical Initiatives in Worcester, stressed the need for what he called “tangible substance projects” like the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences and the commuter rail.

“These are the kinds of things that are going to sell in the outside world,” he said. “Our mantra has to be substance. It has to be product.”

5. Spreading The Word

O’Sullivan said Central Massachusetts must do a better job marketing itself and outreach more within the industry to be more successful.

“My sense is we’ve got to continue to show up,” he said. “I think one of the things we need to do is be more proactive.”

He said Worcester officials are getting better at that, such as making presentations to companies and health care entities they hope to bring to the area.

Susan Windham-Bannister, president and CEO of the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center, agreed. She stressed the importance of events like WPI’s venture forums, which bring potential investors before startups and industry conferences — like last month’s BIO International Convention in Boston.

“We’re working really closely with the central part of the state to make sure that any companies that are coming to Massachusetts are aware of the assets,” she said. She explained that those include a lower cost of doing business, the presence of skilled workers and researchers in engineering and medicine, and the ability to perform clinical trials at UMass Memorial Medical Center and Tufts University’s veterinary school in Grafton.

“Entrepreneurs have great support systems,” she said.

Read more