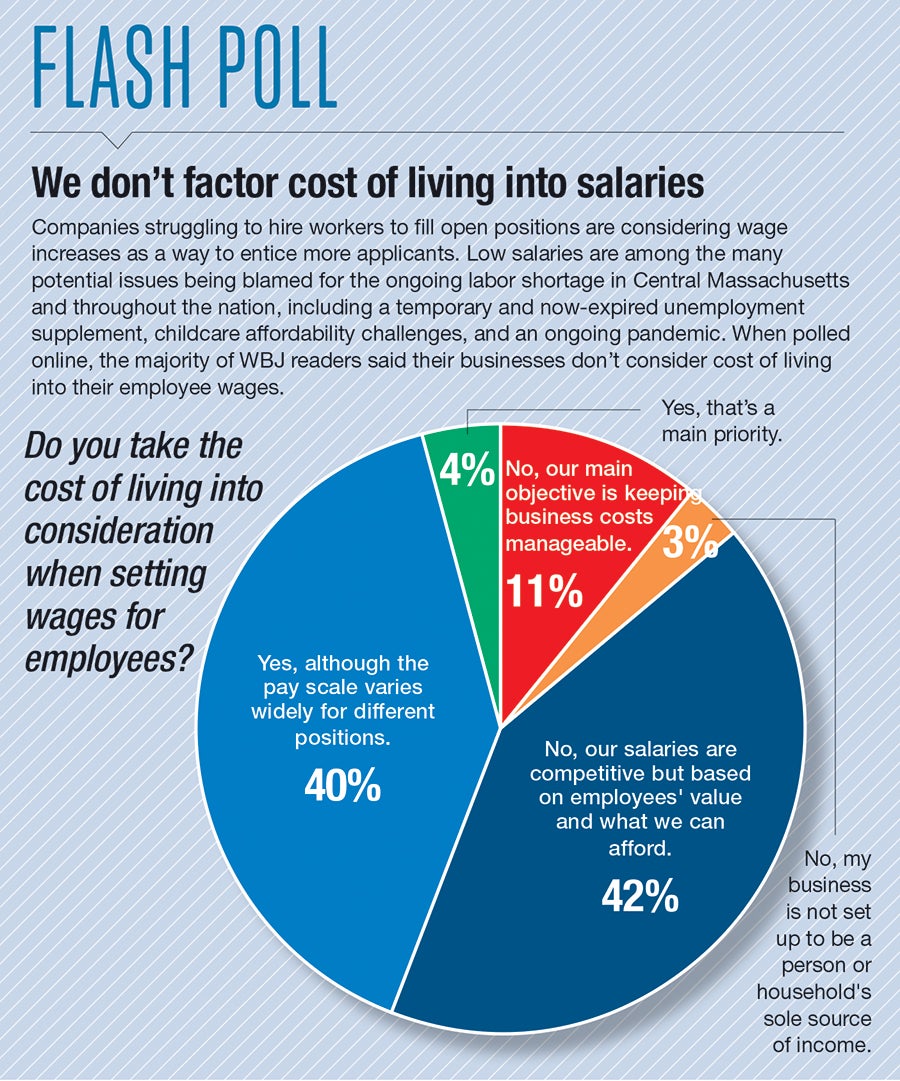

When employers set wages, a lot of factors go into the decision. They ask themselves a variety of questions, including what they can afford, what is industry standard, what’s the market rate for the position, and, in some cases: Is this a living wage?

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When employers set wages, a lot of factors go into the decision.

They ask themselves a variety of questions, including what they can afford, what is industry standard, what’s the market rate for the position, and, in some cases: Is this a living wage?

The idea of a living wage, however, is fickle. There is no clear, agreed-upon definition for what it means.

“It’s really not a number … It’s an amount of money that people need to earn in order to have an acceptable standard of living,” said Alexander Smith, associate professor and economics program director at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

From his perspective, that means bringing in enough money to pay for reliable, safe housing, cover necessities like food and health care, and have a little extra room in the budget to save and cover unexpected expenses, like surprise medical needs. In places like Worcester, where public transportation is imperfect, that standard of living likely includes affording a vehicle.

As employers lament persistent staffing shortages brought on by the COVID pandemic, often in low-wage industries, workers have unprecedented bargaining power to pressure employers to raise wages, and resistant employers may find themselves without much say in the matter, if they want to secure staffing levels.

The data

In September, a U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics report detailed open jobs and employee turnover as of the last business day in July. Per that report, the number of open jobs in the country increased by 749,000, coming to a total of 10.9 million. Inversely, 6.7 million hires took place nationwide.

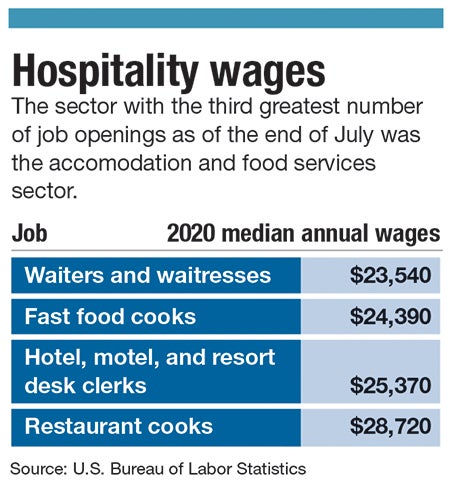

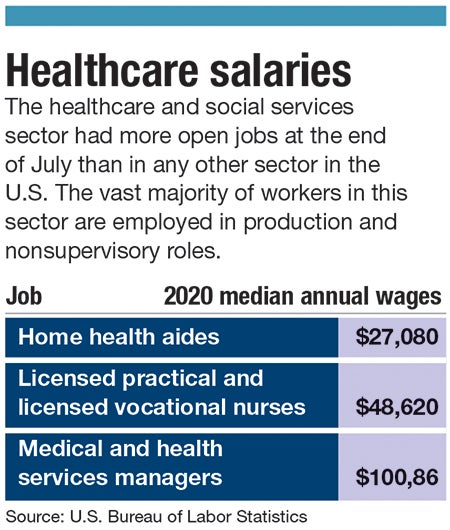

The sectors with the greatest increase in open jobs were health care and social assistance, finance and insurance, as well as accommodation and food service. The hiring issues in the first and third industries are the most widely talked about both anecdotally and in news reports, including locally in Central Massachusetts.

Per the same report, there were 2.026 million open jobs in the Northeast in mid-summer, a figure which had been steadily rising for the previous three months, as well as 1.005 million hires. In July the year prior, there were 1.2 million open jobs in the Northeast, in comparison, and 1.15 million hires.

Because the sector is so outwardly facing, the food service industry has received outsized attention for its unemployment rate (9.4% nationally in August) and the impact it’s having on employers and customers. The median average annual income for food prep workers and servers, including fast food, is $23,440, nationwide.

In Worcester, where the average rent cost for a one-bedroom apartment is $1,363, according to the website Zumper, such an annual income would be difficult to impossible to live on after taxes and other necessities are accounted for, nevermind if the workers in question have dependents or are the sole breadwinner for their households.

“When we think about a labor market, there’s some degree of supply done by the workers … then there’s the demand by the firms, the number of workers that firms want to hire,” said Wayne Gray, professor of economics at Clark University in Worcester. “Both of those numbers depend on the wage. At a very low wage, firms might be happy to hire a lot of workers, but a lot of workers may not want to work.”

Consequences

In the great debate about labor shortages, employers and politicians have been quick to point fingers at the temporary, pandemic-induced increase in national unemployment benefits, which ended in Massachusetts around Labor Day. Although economists are keeping an eye on what happens to employment levels now with the booster gone, it’s too soon to say exactly what kind of an impact that cushion was having on the workforce’s willingness to take low-paying jobs.

Aside from paying bills, the extra unemployment benefits allowed low-wage workers to reassess their career plans, providing a period of time during which they could think about moving on to different, possibly more stable sectors.

“That’s part of what’s happening is the firms who would be hiring those low-wage workers think they can go back to two years ago and now we’re back to normal; but the workers have changed, whether because they've had other benefits or found other opportunities,” said Gray.

In closing the labor gap, particularly in the healthcare and the hospitality industries, a question remains of whether addressing the issue would be as simple as raising wages, and would doing so be smart for the economy. Conversations like these often prompt ominous forecasts about wide scale inflation, after all.

Economists aren’t necessarily convinced.

“We’ve been watching wages for the highest earners go up and up and up, which is why we’ve seen more wage inequality … Where’s the inflation for that? There might be fewer of them, but aren’t they getting paid more?” said Robert Baumann, a professor in the economics and accounting department at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester.

It’s true, he said – as did all economists interviewed for this story – raising, for example, restaurant employee wages, may ultimately result in increased restaurant prices. Wide-scale inflation, however, is unlikely, Baumann said. It’s one piece of the economy, and the U.S. has checks and balances built in to respond to such a scenario, if it were to happen.

“My counter for that is that's why we have monetary policy, to watch out for that. Even if [those who predict wide-scale inflation] are correct … we’ve got a federal bank and a central bank that knows how to deal with inflationary periods,” Baumann said.

Gray said wide-scale inflation could be an issue if the minimum wage were to be raised year after year. But the federal minimum wage is $7.25, and it hasn’t increased since 2009. The Mass. minimum wage is $13.50 an hour, and will hit $15 an hour in January 2023.

At the current rate, a person working 40 hours per week at the state minimum wage for 52 weeks in a row would make $28,080 annually, before taxes. That will increase to $31,200 per year when the wage hits $15 an hour in a little over one year.

“More broadly, low-income workers provide a lot of services in the community,” said Smith, of WPI. “So pick your industry, you often have some people providing labor in that industry, and if they’re just not making enough to enjoy decent lives, then the work they’re able to provide will suffer.”

And in the long term, Smith said, a person falling into poverty is a bad economic outcome, and if they have children, will probably have a negative impact on their health and economic outcomes, as well.

“This is a generational thing that does have long-term consequences,” Smith said.

Employers may be nervous to raise their wages, both Baumann and Gray said, because of long- and short-term consequences. There’s a risk they may lock themselves into paying higher wages when it’s possible the economy may ease back, at its own pace, to previous norms, leaving employers either stuck paying higher wages than they’d prefer or deciding whether to prompt worker fury over decreasing rates.

Regardless of how it plays out, Gray said the labor shortage among low-wage workers will level out in some fashion. A year from now, he said, he doubts we’ll be having this conversation.