When it comes to reaching the state’s renewable energy goals, cross-sector collaboration is the name of the game, according to speakers and panelists at WBJ’s 2023 Mass Energy Summit.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When it comes to reaching the state’s renewable energy goals, cross-sector collaboration is the name of the game, according to speakers and panelists at WBJ’s 2023 Mass Energy Summit.

“The entire economy depends on the use of fossil fuels … To end that dependency is going to be really, really difficult,” David O’Connor, president of Boston-based O’Connor Energy Consulting, a panelist at the May 12 summit, said about the barriers to clean energy development.

Many of the speakers used as their guiding lights the state’s Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2050, released in December, which outlines the government’s plan to reach net-zero greenhouse emissions in 27 years. A complicated goal, achieving it will require public and private partnerships, including cooperation from business and residential communities, as well as removing barriers related to the wholesale power market, acquiring technical expertise, and permitting processes related to greenlighting clean energy power projects.

Revolutionizing building

To that end, panelist Joanna Troy, director of energy policy and planning at the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources, told attendees they should expect to see more working groups and councils devoted to cross-sector collaboration in the coming years.

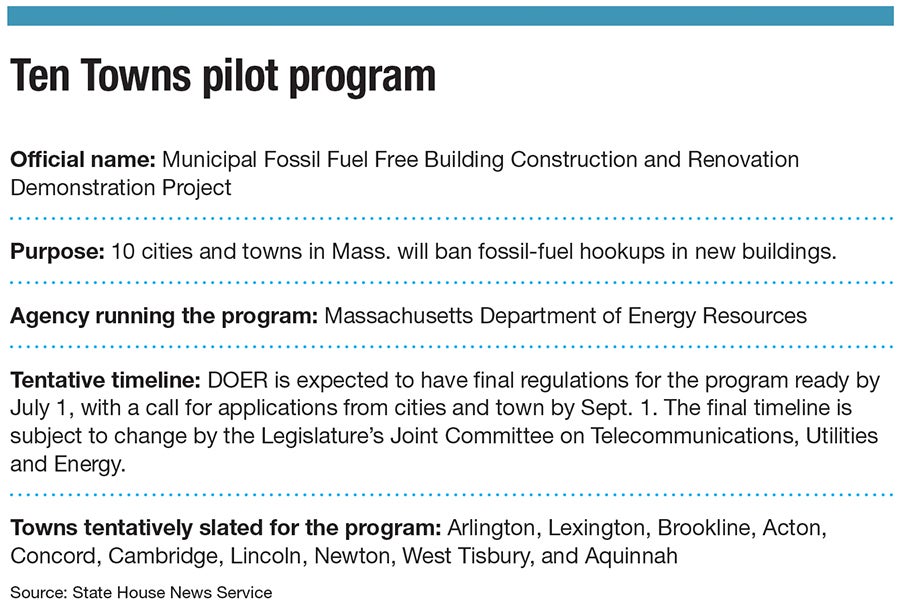

One project Troy highlighted was the Municipal Fossil Fuel Free Building Construction and Renovation Demonstration Project, colloquially referred to as the Ten Towns pilot program. The program, according to the Massachusetts Municipal Association, will prohibit or restrict fossil fuel use for new building construction and large renovation projects, allowing the Department of Energy Resources to collect data on fossil fuel bans, with the goal of informing future policy development. The sole Central Massachusetts community slated for participation is Acton, according to the MMA. Other towns include Aquinnah, Arlington, Brookline, Cambridge, Concord, Lexington, Lincoln, Newton, and West Tisbury.

Describing it as a demonstration project, Troy said data collected will allow officials to see if there is a noticeable benefit.

“We do think there will be,” she said.

The implications of such an effort cannot be understated. In addition to cost impacts, the program will require a complete construction paradigm shift in participating communities.

“That’s going to change the way builders build,” O’Connor said. “That’s going to change the way real estate agents sell property.”

Clean energy generation

The Ten Towns program does not have an official start date. However, two of the towns – Aquinnah and West Tisbury – are located on Martha’s Vineyard, where New Bedford-based Vineyard Wind is planning a 62-turbine offshore wind farm whose construction is supposed to begin within weeks, according to May 15 reporting from The Martha’s Vineyard Times. The wind farm will be located 15 miles south of the island and is expected to begin producing power by the end of 2023. Vineyard Wind bills itself as the country’s first utility-scale offshore wind energy project and predicts it will generate electricity equivalent to powering 400,000 homes and businesses in Massachusetts.

Panelists at the energy summit highlighted the project several times and identified offshore wind as a clean energy realm where the United States is behind, relative to Western Europe, where O’Connor said wind farms have been functional for about a decade, resulting in established supply chains and experience-based technical know-how.

To get to that point will require a concerted effort. All of the projects panelists referenced required some level of cooperation from local and state government groups, as well as local business and residential communities, including the Ten Towns program, Vineyard Wind, and municipal aggregation – a process through which local governments can purchase electricity in bulk from a supplier on behalf of ratepayers, typically resulting in lower costs. Moving the state toward its 2050 goals will require that type of multi-sector cooperation as programs develop and come on board.

Solving the NIMBY problem

Panel moderator Michael Ahern, director of power systems at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, summed up the discussion around barriers as a need to restructure the power wholesale market, acquire technical expertise to build offshore wind, and expedite the permitting process for large-scale power-producing projects, which often face siting challenges, including those related to community environmental and aesthetic concerns, as was the case on the Vineyard.

“Ignoring community complaint is not the solution, either,” Troy said, arguing stakeholders need to increase engagement and transparency around clean energy initiatives, which includes deflecting the idea that promoting alternative energy is an ideological endeavor. Instead, she encouraged attendees to remember clean energy results in real cost savings, including for businesses.

To get there, the state provides a number of incentive programs to help and encourage business leaders to shift their energy sourcing toward renewable alternatives to fossil fuels, among them the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, an economic development agency helping business owners connect with the right programs for them. The agency works with and supports decarbonizing building, clean transportation, net-zero grid initiatives, as well as offshore wind, according to its website.

“We all need to try and get over our inertia and reluctance to change,” O’Connor said.