With the medical world on the cusp of an artificial intelligence revolution, researchers and clinicians are excited about the potential and wary of technology implicitly reliant on human bias

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Artificial intelligence technologies have the potential to reshape how diagnoses are made, if not revolutionize diagnostics in medicine. Already, technologies exist to streamline the diagnostic process and detect illness before a physician can.

But the technology should not be fully relied upon just yet.

“The algorithm can be only as good as the data that we give it,” said Elke Rundensteiner, professor of computer science and founding director in data science at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

It’s a mistake to think that technology immediately holds less bias than humans. Artificial intelligence programs aren’t developed in a vacuum: In medicine, they are fed thousands of data points from practitioners based on real data from real patients, and the AI learns to analyze based on data not always representative of diverse groups.

Participation in clinical trials in medicine is not representative of all populations, said Rundensteiner. According to a 2021 report in the Journal of the American Medical Association, less than 5% of clinical trial participants are Black.

“If the data is biased and you give it to an algorithm, then the system might be neutral, but the bias is already baked in,” she said.

Helpful for certain populations

Dr. Neil Marya, a gastroenterology specialist at UMass Memorial Health and assistant professor at UMass Chan Medical School in Worcester, is researching new diagnostic tools for pancreatic cancer and bile duct cancer. While a few years from clinical use, said Marya, the technologies are showing promise through observational use.

The AI is trained on tens of thousands of image and video data points from patients with and without cancer. The goal is to use computer learning to diagnose cancer, but for now, it is not enough to rely on for a definitive diagnosis.

“We're not acting on the AI right now. It’s just in the background, and we are understanding how it works in these cases,” Marya said. For now, humans outrank the technology in declaring something cancerous or noncancerous. They will not yet use the technology to recommend chemotherapy or surgery without a definitive biopsy, he said.

In some cases, the AI has said something is cancer far before a pathologist has been able to make a diagnosis, Marya said. However, at other times, it has been incorrect, giving a false negative. In either case, the data the AI is pulling from is potentially more useful for certain demographic groups than others.

“It would stand to reason to say, ‘AI, should supersede all that implicit bias since it’s not influenced by one's upbringing or other things.’ But the issue is that for a lot of these AI models that we're developing, they're being developed at these major academic medical centers in areas or regions where there are only certain types of patients that are getting access to the care that generate the data necessary to create these artificial intelligence models,” Marya said.

Marya’s original work on the topic of pancreatic cancer models was at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, where he said a majority of the patients they saw were white males over the age of 60. Due to the regional bias of Southern Minnesota, there were a very low number of African Americans in the study, he said.

So while the results were very promising, indicating the possibility artificial intelligence programs could be trained to detect pancreatic cancer before physicians could use the current gold-standard method of biopsy, they might not be applicable to other demographic groups.

“There's no denying that it's a heavily biased dataset towards a particular type of person. And it might not perform as accurately or maintain these really nice performance parameters when we put it out into practice,” Marya said.

Getting the best results

While there is cause for a measured introduction of the new machine-learning technology into the practice of medicine, increased access to software physicians can use in tandem with their expertise may increase access to needed health care in less serviced areas, said Dr. Bernardo Bizzo, senior director of the Data Science Office at Mass General Brigham in Boston.

Bizzo’s team works on software as a medical device, he said. With success, they have developed technology to detect early acute infarcts in some instances that neuroradiologists did not. In his estimation, a wave of new, similarly capable software is here.

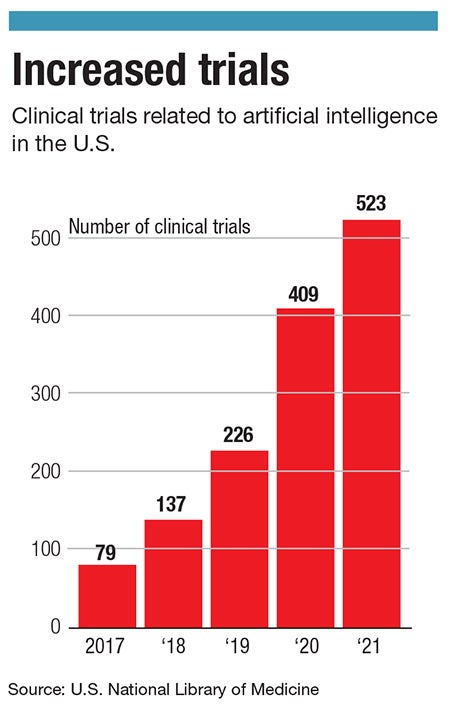

“We are at an inflection point with this [AI] technology. The expectation is that there will be a lot more AI products made available at a much faster pace,” he said.

Marya said he may appear too nervous in his full adoption of the technology, but he just wants to work out the issues. “I love the research we're doing; and I'm really passionate about it, and I trust it; but I think we need to be measured with how we approach this,” he said. “It's really important to do this right.”

Rundensteiner said, based on how the public responds to AI overall, patients will continue to want the human element in the forefront, even if the technology is delivering more definitive answers.

“Most [patients] would probably still say that they want that human touch right now. But I believe it's just a matter of time until we might want that convenience, and the human is maybe just a face because even that human that they're talking to has computers behind them,” she said.

Patients and their families are often less skeptical than expected, said Marya. When it comes to life-threatening illnesses, patients and their families are open to most technologies with minimal hesitation.

“If there was a better way, a more accurate way to get a diagnosis sooner, they're all for it,” he said. “A lot of people, for good and bad, I think they just want the most accurate diagnosis done as soon as possible. And however that's done, I think people just want the best results.”