MassHousing and the Massachusetts Housing Investment Corp have teamed up to launch what they say is the largest publicly led financing program of its kind in the country.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The current economic conditions impacting real estate development have led to delays of some of the biggest high-profile developments in Central Massachusetts, impacting even some of the largest property development firms in the country.

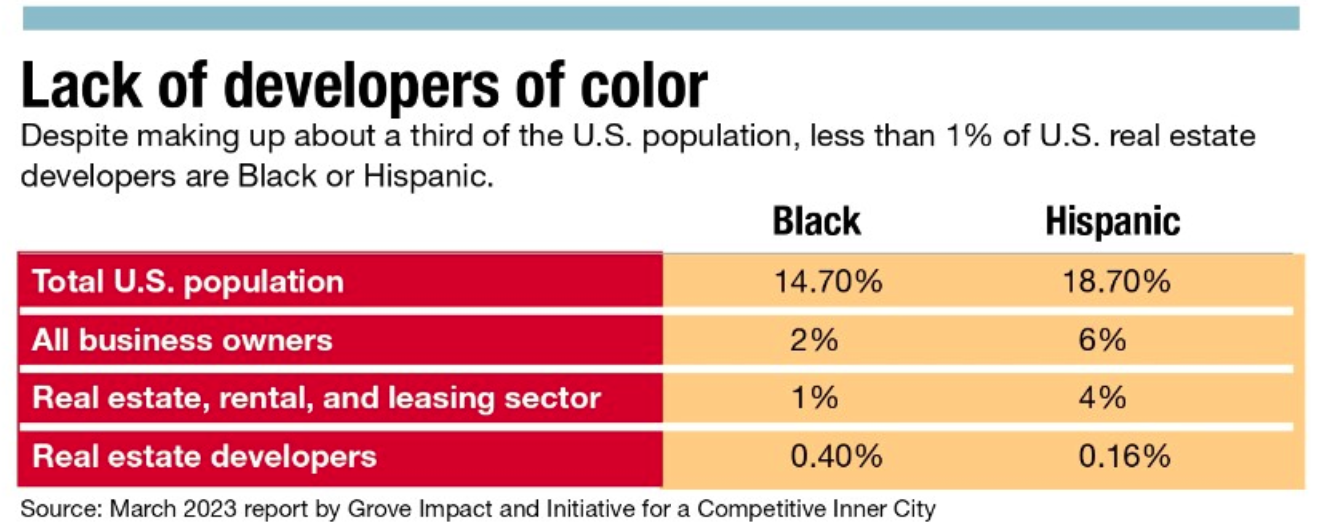

At the same time, the real estate development space is facing a stunning lack of diversity, according to a March 2023 joint study conducted by Roxbury-based nonprofit Initiative for a Competitive Inner City and Washington D.C.-based consulting firm Grove Impact.

The report found Black developers make up 0.4% of the industry, while Hispanic developers make up 0.16%. Further highlighting the lack of diversity in the space, the report found 111,013 of the 112,046 estimated real estate developers in the U.S are white.

In an attempt to both diversify the development space and help address the state’s housing crunch, MassHousing, a quasi-public agency focused on affordable housing, and the Massachusetts Housing Investment Corp., a Boston-based private nonprofit, have teamed up to launch what they say is the largest publicly led financing program of its kind in the country.

Announced in May, the Equitable Development Fund is a $50-million effort designed to address disparities in access to capital in real estate. The fund aims to break down long-standing barriers keeping developers from underrepresented communities sitting on the sidelines, watching others benefit by developing the neighborhoods they grew up in.

Helping Gateway Cities

The fund will work by offering underrepresented developers who have experience in developing rental, homeownership, or mixed-use projects the chance to access working capital lines of credit and standby letters of credit.

Applicants are required to be previous or current residents for a period of five years or greater in one of the state's 26 Gateway Cities, which includes the Central Massachusetts cities of Fitchburg, Leominster, and Worcester. Developers from Framingham are also eligible, as are residents from census tracts where 51% or more of the households earn less than 80% of the area median income.

Those who don’t fall into one of the categories can still receive funds if they can provide documentation showing social disadvantage, including economic insecurity, barriers to educational access, disability, or membership in a group historically subject to prejudice.

“What this fund does is gives [underrepresented developers] the agency to go off and do projects when they're the first to see that there's an opportunity for a duplex on their street,” said Moddie Turay, CEO and president of Massachusetts Housing Investment Corp. “They're probably the first to hear about those opportunities when their neighbors are thinking about selling. I think that what we're trying to do is empower those people that are active in the real estate space, want to build capacity, give them the tools that they need.”

Participants are required to seek housing-related developments in the geographic areas outlined in the eligibility requirements. MassHousing and MHIC want to raise an additional $25 million for the fund from private investors.

Knowing the landscape

Developers from underrepresented communities are uniquely equipped to serve the housing needs of those areas, said Walter Weekes, founder of Optimum Investment Realty Development.

“Part of what we bring to the table as minority developers is we often know from different perspectives what will work in various communities,” Weekes said. “Because oftentimes, if you live in those communities, you know the landscape.”

Developers from underrepresented communities, even figures like Weekes who have been successful in the development space for years, say capital access remains the biggest hurdle.

“Some of the more established firms are able to lock into more favorable terms, get better rates, or gain access to some of the funding that might be available through the various state agencies,” Weekes said. “What I have to do, what many other minority developers have to do, is to try to see how we can partner with other established firms to show some leverage. Oftentimes, you may not have the balance sheet needed to move a deal forward.”

Optimum has a Boston address, but Weekes has been based in Worcester for the last quarter century, where he’s a member of the Worcester Redevelopment Authority. He’s working on two development projects in the city.

“I do believe that this particular fund is moving things in the right direction. I think if the program is able to accomplish its goal, it will help minority developers have access to funding,” said Weekes, noting this type of financial support is critical for covering soft costs or unexpected expenditures with the potential to derail projects.

Rebecca and Daniel Yarnie, the Worcester-born owners of Northborough-based Polar Views, are involved in a number of developments, including a mixed-use development at 34-36 Harrington Ave. in Shrewsbury and a proposed 36-apartment building at 39 Lamartine St. in Worcester, near the Polar Park baseball stadium.

They have learned first-hand successful developments are a process involving hundreds of steps which can quickly turn into hurdles.

“It's like there's like a ripple effect,” said Daniel Yarnie. “So that's why sometimes projects prolong and people go broke. So it's like, we all need to come together to figure out a way to make it easier.”

Capital from traditional sources can be tough to get.

“Obviously, the banking industry too is very, very tight right now. Nobody really wants to take on much risk,” Rebecca Yarnie said. “A lot of the money is on soft costs and unforeseen expenses. So it just ends up coming out of your own pocket.”

To find other avenues of capital, the Yarnies are looking to other industries. They’ve launched Polar Views-branded merchandise and are working to open Finest Trees, a Shrewsbury-based cannabis delivery company.

A gateway to housing

With even some of the largest developers struggling to finance projects, the current environment is even tougher for developers from underrepresented communities, said Turay, the head of MHIC.

“Just imagine through that with the most accomplished developers facing all the financing problems, now imagine an upstart [developer] and what they're facing. Therein lies the challenge.” he said. “You've got banks that say ‘Hey, we're not taking on new banking relationships at this time.’ It’s just a whole host of things that come into play that we're trying to help them solve for.”

A major focus of the fund will be Gateway Cities.

“We are really focused on Gateway Cities, we're focused on places in the state that were badly hit by COVID, and places that are part of the low-income housing,” Turay said.

Financial support is needed, especially for cities like Fitchburg and Leominster hoping to bring in more residential units, said Roy Nascimento, president and CEO of the North Central Massachusetts Chamber of Commerce.

“Real estate development is expensive, especially in some of the older Gateway Cities where we're trying to incentivize more housing in downtown business districts,” Nascimento said.

In November, the chamber launched its Regional Business Investment Fund, designed to provide low-cost financing for real estate projects in northern Worcester County having difficulty finding financing.

“With those types of developments in particular, like the developments that we've helped with our investment fund, those are typically older buildings that require more expense to redevelop into housing,” Nascimento said.

Both Weekes and the Yarnies noted the importance of understanding the labyrinth of necessary approvals and having a professional network to assist with navigating these processes.

In addition to providing a source of funding, the Equitable Developers Fund will provide help with the ins-and-outs of locating affordable housing development opportunities and financing.

“It’s important to note that MassHousing will be taking on the technical assistant aspect of this. So it's not just, ‘Here's money, go pay us back,’” Turay said. “It’s so we help these organizations actually build capacity and not just dollars. It's really trying to surround them with support.”

Generational opportunity

Both the Yarnies and Weekes feel, with the proper support, the next generation can benefit from more developers from minority communities and other underrepresented backgrounds.

Weekes, who receives mentorship from Rob Dickey, executive vice president of Boston-based Leggat McCall Properties, via the Boston nonprofit Builders of Color Coalition, hopes his career will inspire underrepresented developers.

“That's part of my motivation to get into the real estate development space, to be able to try and make a difference and blaze the trail to be an example to other minority developers coming in, because there's not many that look like me in the space,” he said.

The Yarnies hope they can show their four kids real estate can be a prosperous industry. They hope to provide them with a financial foothold.

“We're kind of aiming for a generational wealth type of thing,” Rebecca Yarnie said. “We're not really looking at the dollar bill right now.”