In Central Massachusetts, the confidence banking executives have in the brick-and-mortar model is unwavering.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Banking is not what it used to be. The days of waiting in line to cash a check with a teller or apply for a credit card are long gone, replaced with apps allowing consumers to transfer money with the swipe of a finger.

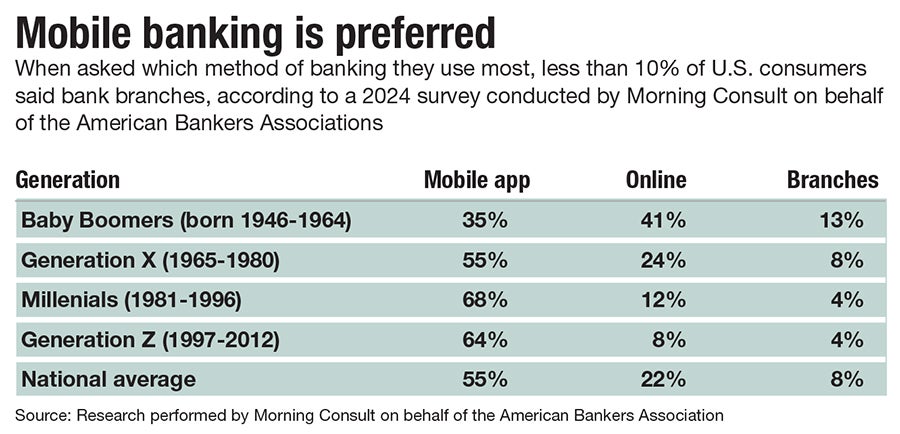

Showing up to an in-person branch is becoming rarer for those in the U.S., a shift reflected in the number of brick-and-mortar locations available.

The country has lost about 1,646 bank branches every year since 2018, according to credit-building platform Self Financial. Self Financial asserts physical bank branches could be obsolete in the country by 2041.

But in Central Massachusetts, the confidence banking executives have in the brick-and-mortar model is unwavering: The role branches play in the community, in relationship building, and in financial success are the key to their longevity.

“We believe as a community, we have a responsibility to be an institution that is centered here, that's focused here, that's open to all people here, and that we become an institution that means something in people's lives,” said Michael Welch, CEO of Whitinsville-based UniBank.

Forced acceleration

Like all face-to-face services, in-person banking was turned on its head with the onset of COVID-19, pushing customers to mobile and online banking.

“The move to digital was already on its way, and COVID accelerated that,” said Altaf Ahmed, executive vice president of retail banking at Cornerstone Bank in Worcester.

The pandemic forced even those technologically averse to adopt digital-based solutions faster than they necessarily would have.

To adapt to the rapidly changing times, Natick-based Middlesex Savings Bank leaned into its drive-up network, said Bryan Christensen, executive vice president and chief community banking officer.

When its lobbies closed, Middlesex Savings quickly pivoted by expanding the services available through drive-up windows, offering everything from opening a business account to wire transfers to new debit cards.

That switch in reliance was fairly short lived, though. Once branches began to open up again, Middlesex Savings quickly began to see people back in-person. While banking foot traffic has been steadily decreasing over the years, Middlesex Savings is back to where it would have been in that trajectory had there not been a pandemic, said Christensen. Customers are frequenting branches less often, but patrons spend more time during those visits, tipping the scale closer to balance.

COVID was not a main catalyst for the nation’s overall decrease in branches.

As the spurs of society continue to quicken, people’s time is consolidated with the needs of work and family. Thus, peoples' ability to access a branch is becoming restricted, and not all banks are able to stay open with extended days and hours, said Nicole Almeida, senior vice president, chief of staff at the Massachusetts Bankers Association in Boston.

Mergers and acquisitions are another catalyst for bank closures, as a post-merger bank will seek to find efficiencies, including by closing banks and laying off employees, Almeida said.

“It's always a very mindful, purposeful discussion within an organization,” she said.

Picking and choosing

The cost to open a brick-and-mortar branch varies with location and size, but nonetheless it’s a multi-million dollar investment every time, said Christensen.

That hasn’t deterred Middlesex Savings. The bank boasts one of the highest numbers of local branches, with 32 throughout Central Massachusetts.

When selecting a location for a new branch, Middlesex Savings looks for areas that bank leaders think will respond well to a community bank and what it has to offer. Choosing a location is a matter of opportunity: Great locations don’t come around often, especially in smaller Central Mass. towns, said Christensen.

“It's almost as much an art as a science,” he said.

In January, Cornerstone Bank announced it would open a location this spring in Worcester’s Tatnuck Square at the site of a former Santander Bank branch. But moving into an old bank location doesn’t make the move-in easier, said Ahmed.

Branches in the region were built 40 to 50 years ago, and branches need to be updated to reflect changing banking preferences. Branches need fewer teller stations and less space for long lines and need more private space for consultations and one-on-one meetings.

“It's what customers need,” said Ahmed.

UniBank opened its second Worcester location on Green Island Boulevard across from the Polar Park baseball stadium in the Canal District, part of the bank’s strategic investment into the neighborhood. The bank has been associated with the baseball stadium since becoming one of the founding partners of the Worcester Red Sox, helping to bring the team to the city from Pawtucket.

When UniBank learned The Revington apartments were opening across from the stadium, the bank jumped at the chance to open up shop in the building’s bottom floor.

“We want to be a part of that exciting density building that they're trying to do here,” Welch said.

Opening the branch is a risk, Welch said, as most of the new Canal District residential developments haven’t opened yet.

Changing needs

Having a physical bank in close proximity is one of the most important factors customers consider when choosing a bank, said Christensen.

While the likes of checking an account balance or transferring funds to savings have gone digital for most clients, customers do walk through branch doors needing assistance with complex needs, such as lending and cash management needs and setting up their children for financial success. Today, branches serve as centers for advice, he said.

Older people typically utilize branches more than younger ones, Christensen said, in part because they’ve been using them their whole lives. Long-term customers will come to the branch just to say, “Hi,” to their favorite banker.

Younger generations are still interested in branches, he said. Millennials will often frequent Middlesex Savings because they feel they don’t have a strong financial background and to have face-to-face conversations about credit, savings, and budgeting.

“They don't want to come by the branch every day. They don't want to come even once a month, but they want to know that they've got something,” said Christensen.

Parents are coming into branches to access financial literacy information and services for their children, said Ahmed, a need banks weren’t seeing 25 to 30 years ago.

“That’s where all banks play a very vital role in making sure that we're providing education, we're providing information, and we're providing tools for our customers to succeed and achieve their goals,” said Ahmed.

Community-centered banking

In-person banking is where relationships are formed, and relationships are the linchpin of community banks, said Welch.

“That's our bread and butter,” he said.

A bank’s ability to lend and donate to a community, whether through volunteer or physical dollars, relies on boots on the ground and in-person interactions, said Almeida.

That is the importance of being locally headquartered for Welch. UniBank annually donates about 10% of its income to Central Massachusetts, totalling in about $2.2 million last year.

“Banking is a relationship-driven business. So brick and mortar is always going to be important,” said Almeida. “In my lifetime, I don't think that will ever change.”

Because of this interpersonal and economic impact branches have on their communities, Almeida said brick-and-mortar locations aren’t going away.

“For as many years people have been saying branches are going to go away, they're still here,” said Christensen.

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story said Middlesex Savings Bank had 25 branches. The bank has 32.