At such a perilous time, the Worcester County business community is hampered by an uncomfortable problem: In the homogeneous world of business leadership in Worcester County, top officials at the area’s largest and best-known institutions are almost entirely white.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Brandale Randolph, a black business owner in Framingham, has unique insight and experience on the issues of racial injustice and police reform now seizing the country.

Randolph owns the 1854 Cycling Co., a small business designing and building technologically advanced bicycles. He’s also the brother of a man who was killed in 2005 by the Los Angeles Police Department in a raid that took place before cell phone cameras were ubiquitous and such instances could become national news.

“That barely made a blip,” Randolph said of his brother’s death.

Randolph, who was born in Louisiana and grew up in Los Angeles, hesitated when asked his thoughts about the Black Lives Matter movement sweeping the country following the killing of black Minneapolis resident George Floyd by police in Minneapolis in May, along with other prominent cases and videos of such deaths before and after.

Randolph lived in Los Angeles during rioting following the 1992 acquittal of police officers in the beating of a black man, Rodney King. He’s written about his brother’s killing, strongly questioning the police’s portrayal of the incident. The police said they were serving a narcotics search warrant and Brayland Randolph pointed a gun at them.

“God and I still aren’t on good terms – not bad ones, either,” he wrote. “We are cordial. God and I are at peace under a mutual understanding that when we meet face-to-face, I will have a litany of questions. He knows because he made me this way.”

Randolph still feels injustice today. He’s the owner of a company featured in Ebony magazine, Bloomberg and other publications for a mission including employing people who were formerly incarcerated. But he said he’s been rejected twice for Paycheck Protection Program loans, a $669-billion program created by Congress to keep small businesses afloat during the coronavirus pandemic.

It makes him struggle to know how much to speak out.

“Even with this article, I’m not sure if I should do it or not,” Randolph said. “Even talking this way, it could lose me millions of dollars, literally.”

A small minority

At such a perilous time, the Worcester County business community is hampered by an uncomfortable problem: In the homogeneous world of business leadership in Worcester County, top officials at the area’s largest and best-known institutions are almost entirely white.

There are no black leaders among the area’s publicly traded companies. None lead the area’s hospitals or colleges.

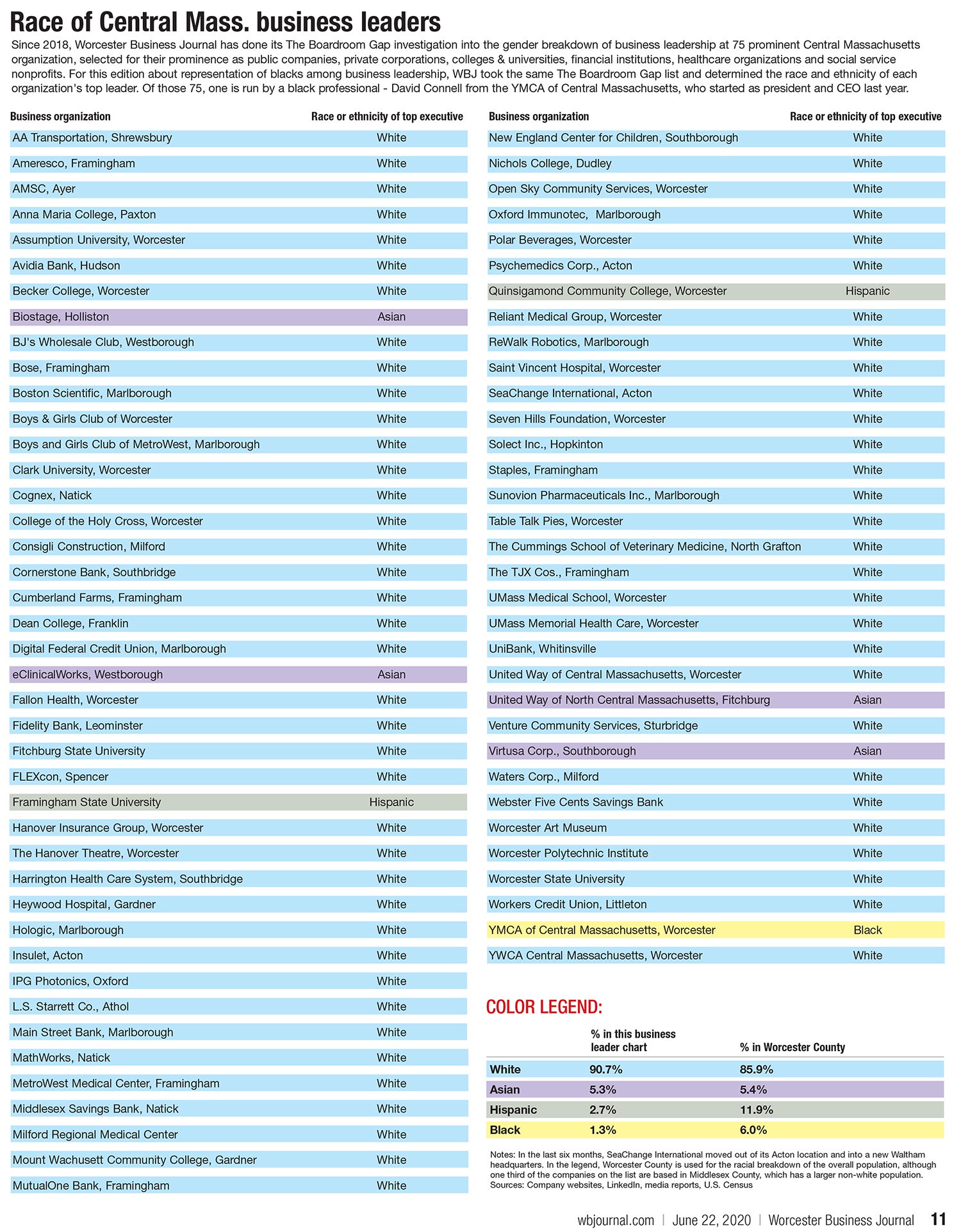

For the last three years for its The Boardroom Gap investigation, the Worcester Business Journal has reviewed 75 of the largest and best-known institutions in Central Massachusetts to gauge gender diversity among top executives and board members. Those reviews have consistently reached the same conclusion: Positions of power – and highest pay – overwhelmingly go to men, and especially white men.

Only one of the leaders of those business organizations – YMCA of Central Massachusetts President and CEO David Connell — is black. A few other black leaders in Central Massachusetts lead organizations not featured on The Boardroom Gap list, including Lou Brady, the president and CEO of Family Health Center of Worcester. Both Connell and Brady were appointed to their positions in 2019.

“It’s important that our voices are heard,” Brady said of black business leaders. “It helps to expand the reality and the understanding of our white colleagues.”

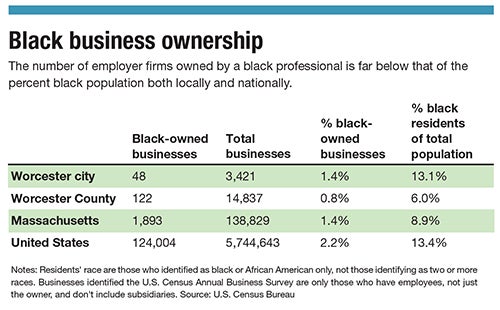

It’s just as rare in Worcester County to find a black-owned business.

Less than 1% of the Worcester County businesses with employees are black-owned, despite black residents making up 6% of the population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

In Worcester city, 1.4% of businesses with employees are black-owned, despite the city’s population being 13.1% black, according to the census.

That lack of diversity isn’t unique to this region. Of Massachusetts businesses with employees, 1.4% are black-owned vs. a 8.9% statewide black population percentage. Nationally, 2.2% of businesses with employees are black-owned vs. 13.4% of the total population.

Only four Fortune 500 companies are led by a black executive.

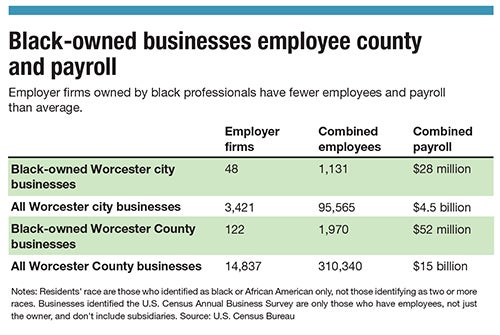

Black-owned businesses with employees tend to be smaller, too: In Worcester County, the black-owned firms average 16 employees per business vs. 21 for all county firms. The average payroll of a black-owned firms in Worcester County is $428,648 vs. $1.02 million for all county firms.

Tangible harm

The disproportionately low number of black-owned businesses in Central Massachusetts and their relatively small size has a direct impact on the black community in the region. Among the reasons: Black-owned businesses are more likely to hire minority employees; the revenue from those businesses is dispersed into black communities; and business owners and executives are seen as community leaders who can speak up on societal issues, like police brutality and institutional racism.

A study from the University of Wisconsin published in 2001 – the most recent study available on the matter – found black workers have been proven to have hiring advantages when there are more black business owners. Looking specifically in Boston, the study found a black-owned business was more than five times more likely to hire a black candidate than a white one. The simple reason, the study found, is those businesses attract and hire more black applicants.

Greater rates of business ownership among the black community in Central Massachusetts would help greatly with financial wellbeing and career opportunities, said Stacey Luster, a black professional and Worcester State University’s assistant vice president for human resources, payroll, and affirmative action and equal opportunity.

“That’s a tremendous asset that we don’t have,” Luster said.

Among the reasons for the low rate of black business ownership in Worcester County is difficulty in finding the financing and capital necessary to start and fund a business, said both Randolph and Milka Njoroge, the CEO of Worcester home healthcare agency Century Homecare.

Njoroge runs the largest black-owned company in Central Massachusetts, with Century Homecare’s 180 employees. She said when she went to get PPP financing to help her business through the coronavirus pandemic, she had to shop around for different banks as the one she normally used wouldn’t provide a loan.

With so few black business leaders, Worcester County is left without many prominent black business voices, something Segun Idowu, the executive director of the Black Economic Council of Massachusetts, said is critical for knowing the experiences black workers have lived.

“We can’t expect that even the most well-intentioned ally is going to bring up these issues all the time or even to get it right all the time when they do,” Idowu said of white business owners and executives who may commit to helping fight systemic racism but don’t have the lived-in experiences of members of the black community.

“You can’t substitute the voices of those being affected with someone from the group that’s affecting them,” Idowu said. “When I think of the voices of allies, it’s not their role to speak on our behalf but to have us at the table and to listen.”

Black business leaders who do have a seat at the table said they value the opportunity but wish there weren’t so few others.

Eurayshia Williams Reed, the owner of the salon Shi-Shi’s Lounge in Worcester and a trustee at Becker College, said the feeling of being the only black professional on a board of trustees or in an industry group is isolating and when two or more are in such situations, they are drawn to each other.

Having so few black-owned or black-run businesses could hamper an ability for black workers to do better in their careers, too. An article in the journal Academy of Management in May cited practices prolonging inequality, including a tendency for those screening candidates to choose those with similar backgrounds and business networks often tend to favor white men.

The impact of COVID-19

The coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated challenges black business owners were already facing.

Black-owned businesses have been hit especially hard by the economic toll of the coronavirus pandemic. A report in May by a research institute at Stanford University estimated 41% of U.S. black-owned businesses were closed – temporarily or permanently wasn’t specified – by the outbreak, the most of any race or ethnicity.

The reason was largely due to the industries where black business owners are most likely to be found. Black-owned businesses are most likely to be in health care and social assistance, followed by transportation, warehousing, and administrative, support and other services, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Black-owned businesses have been found to be less likely to receive federal financial help in the Paycheck Protection Program.

A survey in late April by the New York City investment firm Goldman Sachs found black-owned businesses were less likely to apply for PPP loans than small businesses in total (79% compared to 91%) and less likely to receive funds (40% versus 52%). Black business owners indicated their personal finances have been more greatly hit and they have less cash reserves on hand.

The bleak outlook is becoming harmful to health, too, according to the American Psychological Association, which cited what it called a heavy psychological toll. Racism, it said in May, has become its own pandemic and is associated with a range of psychological consequences, including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Providing opportunities

Increasing the number of black business owners and executives starts early in the pipeline, with education. Reed, of Shi-Shi’s Lounge, works through the Worcester Women’s Leadership Conference to help offer scholarships and through Worcester Technical High School to provide mentorships.

Worcester State is working to help companies overcome implicit bias or lack of cultural competency through its Center for Business and Industry. Another program, called the Teacher Pipeline, aims at diversifying the makeup of teachers in local school systems.

The college has its own prioritized recruitment and professional development programs, Luster said, including when WSU President Barry Maloney recommended she attend a development program for aspiring college presidents, so she could eventually reach that level.

That work has gone on at Worcester State for years, Luster said.

“It’ll never be finished,” she said. “It’s a fabric of our institution.”

Black business leaders in Central Massachusetts aren’t always sure exactly what their role – or of their white counterparts – should be during a national race crisis following George Floyd’s death, but they agree businesses can have an impact between their hiring practices and their platform.

Reed put out that question – “What do we do?” – to colleagues online and didn’t get much of a response.

“I think people don’t know,” she said.

Reed, who serves on the board of the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce, struggled with it herself.

“I’m not one for protesting,” she said, weighing the idea of a Black Lives Matter sign outside her store. “I’m more worried about what the repercussions would be.”

A time to speak up

Kola Akindele, UMass Medical School’s assistant vice chancellor for city and community relations and a black professional, addressed any dilemma he’d face in being an outspoken black voice in business. He called on businesses to not only offer opportunities for discussion but review hiring practices and where they invest their money.

“I don’t really speak out on that many issues, but the way in which the medical school has responded during this crisis would make me courageous enough to speak out and what I want to say,” Akindele said.

Brady, with more than 500 employees at the Family Health Center, believes executives’ duties today are broader than simply focusing on the bottom line. Now, he said, it includes a consideration of society and often includes taking a stand on societal issues. The Family Health Center, which treats a diverse population that is typically lower-income, was one of a series of health centers holding rallies in support of diversity called White Coats for Black Lives.

“It’s difficult to be a black man in America,” Brady said, saying images of police killings of black people have spurred him to recommit himself to using his voice for good.

Njoroge lauded all companies, regardless of the race of their leadership, for taking a stand in favor of equality after George Floyd’s killing in late May in Minneapolis.

“But it’s more important to have an honest look at how those corporations are structured,” she said.

Njoroge sent a memo to her 180 employees in early June with a hopeful message about how protests have spread worldwide. She urged black employees to talk to someone if needed, and for others to reach out to black friends or neighbors and listen.

Njoroge said she’s encouraged protests following Floyd’s killing could lead to greater change than similar racial incidents in the last few years.

“The majority of people looking at that video would see how wrong it is … Maybe it’s the timing of when this happened with somewhat of a paused mode,” she said, referring to the pandemic. “That people had a chance to reflect and say, ‘What did I just see?’”

Other prominent Central Massachusetts black professionals were encouraged by the direction public response to the Black Lives Matter protests is taking.

“It feels like we can’t take it anymore,” Luster said.

“What it’s done is really brought to others’ attention, particularly white people’s attention, what people of color have been going through,” Akindele said.

“It’s the last straw,” said Michelle Memnon, an office supervisor at UMass Memorial Medical Center and a member of the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce’s Diverse Professional Roundtable. “People are tired and fed up … and it’s the younger generation that’s taking the lead, too.”

Idowu is optimistic about companies nationally reacting with more support after Floyd’s death than they generally have in the past.

“This seems to have awoken some sense of urgency in business leaders large or small. We’ve seen way more voices of support,” he said. “We’ve seen a huge shift in how businesses are responding to this crisis.”

Is a simple message of support enough? It’s better than nothing, Idowu said, but still not far enough.

“If they’re saying ‘Black Lives Matter,’ well, thank you for affirming that, but the power of the company is to do something about it,” he said. “Many of these companies hold powerful lobbying sway, so what are they doing about it?”