Health care is a complicated business on all levels, and one of the most confounding aspects of hospital operations is how they’re paid.

Relying on two major sources for revenue — the government and commercial insurance companies — administrators at acute-care hospital realize they’re playing by certain rules that don’t always add up.

For instance, hospitals lose money on patients who don’t have health insurance, despite the existence of a government safety net that’s supposed to help defray those costs. And when it comes to payments from commercial insurers, hospitals aren’t on equal footing.

This fact brought Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester and MetroWest Medical Center in Framingham down to the wire in negotiating a new contract with Tufts Health Plan in December.

As the month wound down, it was beginning to look as if patients insured by Tufts who previously used the two hospitals might have to look elsewhere for care, as the two parties struggled to come to an agreement. Tenet Healthcare, the hospitals’ parent company, wanted to narrow the gap between its payments and those Tufts makes to comparable area hospitals, according to Erik Wexler, regional CEO for Tenet.

“Our goal was to reduce the gap between us and the other major hospitals in the communities (we serve),” Wexler said recently.

The parties did finally settle on a new, three-year contract Dec. 31. Terms of the agreement are private, but Wexler said it was an “equitable” deal that satisfied the goal of narrowing the gap.

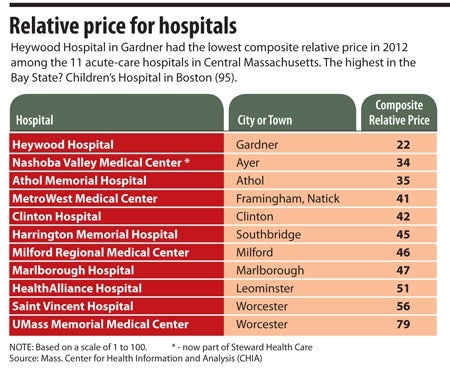

While the public isn’t privy to how much Tufts and other commercial insurers pay Saint Vincent and MetroWest, there are ways to discern who gets paid the most, who gets paid the least, and who falls in the middle. A good metric is relative price, which is calculated through the state’s Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA) based on information submitted by insurers.

Relative price indicates how much a hospital is paid relative to other hospitals within an insurer’s network, without attaching dollar amounts (CHIA is not privy to that confidential information). It’s easy to see where a hospital falls on the price spectrum across all commercial insurers by viewing CHIA’s composite relative price data.

Composite relative price is measured on a scale of 1 to 100, with 100 being the most expensive.

Small community hospitals tend to generate lower composite relative prices, while major urban hospitals and academic medical centers, especially those in Boston, tend to have higher prices.

Heywood Hospital in Gardner, for example, had a composite relative price of 22 in fiscal 2012 (the most recent year for which data is available). UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, an academic medical center that operates the region’s trauma center, had a 79 the same year.

Saint Vincent Hospital’s composite relative price in fiscal 2012 was 56. While updated figures are due from CHIA later this month, the 2012 figure provides a good idea of the gap Wexler referred to, given UMass Memorial’s price of 79. The data doesn’t indicate how much Tufts Health Plan pays Saint Vincent compared with UMass Memorial because CHIA analyzes only relative price for individual insurance companies for the top three commercial payers for each hospital; Tufts wasn’t one of Saint Vincent’s top payers in fiscal 2012.

What’s behind the pricing differences? It depends in part on a hospital’s cost structure. Academic medical centers, for example, tend to generate more expenses. “Disproportionate share” hospitals — those that have a large number of low-income patients who receive payments from the federal government to help care for the uninsured — also tend to have added costs.

But Wexler takes these oft-cited explanations with a grain of salt. He argued that the cost difference between an academic medical center that does research and acts as a teaching hospital, and a hospital such as Saint Vincent, a teaching hospital not attached to a medical school with research activities, are not that great. Academic medical centers generate revenue through their activities that other hospitals do not, which somewhat offsets operating costs, he noted.

“These differences are quite minor and small in nature and should not drive significant disparities between institutions,” Wexler said.

So what does? In the case of Saint Vincent and MetroWest, Wexler said the hospital was not as aggressive as it should have been in negotiating contracts with insurers about a decade ago, and now it’s catching up so that payments increase to match the higher cost of doing business.

Illustrating Saint Vincent’s and MetroWest’s relatively low prices is the fact that they fall in the lowest-cost tier of every commercial health plan they do business with. And while the payments from insurers might be lower, there’s a definite advantage to falling in an insurer’s low-cost tier; out-of-pocket expenses for consumers are lower, so they’re more likely to use your hospital than shop around for cheaper care.

Wexler said it was important to remain in Tufts’ lowest-cost tier to maintain an edge with consumers, something to consider when negotiating payment contracts. If Tenet had negotiated rates that were too high, it could have ended up in a higher tier. (Officials from Tufts Health Plan, based in Watertown, declined to comment for this story).

Ed Moore, president and CEO of Southbridge-based Harrington Healthcare, knows what it’s like to walk this fine line. Despite running a small community hospital system, Harrington has struggled to achieve low-cost tier status with insurance companies because of its large number of patients covered through Medicare and Medicaid. The money Harrington loses on them has to be made up through somewhat higher commercial rates, Moore explained.

But by holding the line on insurance rate increases, Harrington was recently able to move into a lower-cost tier within the Blue Cross Blue Shield network. Moore hopes that will incent more Blue Cross patients to seek care at Harrington rather than shop around. He hopes that what Harrington loses in payments by moving into a lower-cost tier will be made up by higher patient volume.

“We think, philosophically, that more patients would rather stay local,” Moore said.

Better care at higher prices?

A look at pricing disparity for specific medical procedures at various Massachusetts hospitals reveals that higher spending does not actually lead to better outcomes for patients, according to the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission’s 2014 Cost Trends Report.

The HPC, an independent state agency that oversees cost and quality of care, analyzed 2012 data on spending and outcomes for three common, high-cost procedures, including hip and knee replacement, and angioplasty, or “percutaneous coronary intervention,” which prevents heart attacks.

The report compared prices between academic medical centers and the state’s teaching hospitals, as well as New England Baptist Hospital, which specializes in orthopedic surgery and musculoskeletal diseases, and found that academic medical centers received higher-than-average payments for the same services, but quality was not better, based on such outcomes as patient mortality and readmission and complication rates. The HPC report suggests that this “indicates a potential opportunity to decrease health care spending, either by shifting care to more efficient settings or by increasing efficiency and decreasing payments within a given setting.”

Despite factors that hospitals often cite to explain higher costs, David Seltz, the HPC’s executive director, said the difference in how much hospitals are paid is “most closely tied to market leverage and the ability of the provider to negotiate contracts with commercial insurers (to their advantage).” But as the number of high-deductible insurance plans grows, requiring consumers to pay for more of their medical expenses, Seltz predicted patients will begin to shop around for the most affordable services, and that should put pressure on providers to cut costs.