Efforts are underway from Central Massachusetts legislators on both sides of the political aisle to lessen the burden for borrowers.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The second Quinsigamond Community College President Luis Pedraja learned the Worcester school would be receiving $9 million in institutional aid from the federal CARES Act funding, he wanted to use a portion of the relief to forgive student debt for students enrolled during the pandemic.

In tackling student debt forgiveness directly, Pedraja and his team effectively took a contentious debate – what to do with the country’s $1.73 trillion in student debt, as reported by the Federal Reserve – into their own hands. It’s a small piece of a much larger challenge up for debate on the state and national levels, as the unprecedented amount of education debt held by U.S. borrowers has exceeded national credit card debt.

The money at QCC – including $9 million to be spent directly on student aid, plus the $9 million allotted for institutional support – was distributed to the college in May, and on June 9, QCC announced it would use $2.5 million to forgive student debt held by the college.

“To me it was important to remove as many barriers from students [as possible],” Pedraja said. “A lot of the students were impacted significantly by the pandemic and most of that impact had some financial bearings.”

Pedraja said the decision was as much an investment in the community as it was an investment in QCC’s students, many of whom faced employment challenges, are single parents, or serve as the lead financial provider for their families. Although most people think of undergraduate students as fresh high school graduates living in dorms, Pedraja said, the average age of QCC’s students is 25.

“They’re veterans. They're older adults that are trying to reinvent their lives,” Pedraja said.

Massachusetts, by the numbers

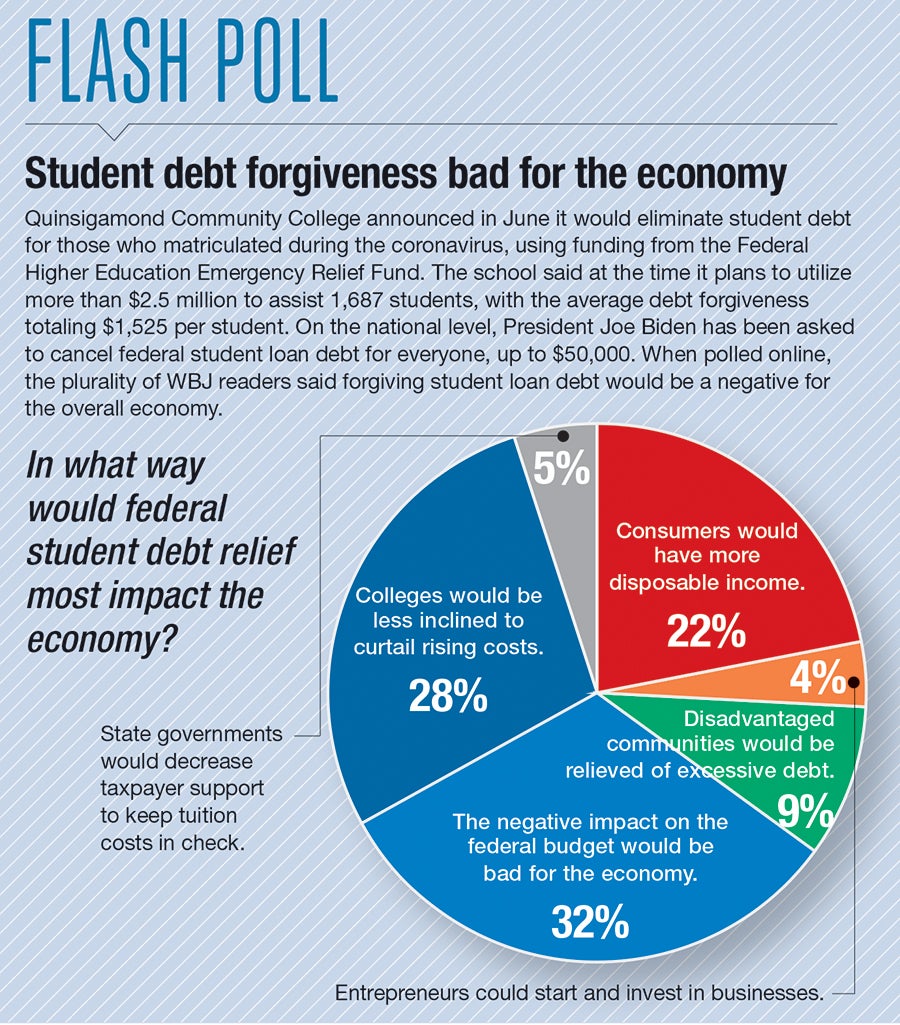

Arguments against student debt forgiveness are almost as many as arguments in favor. A national debate with local implications, those against it argue forgiving debt would disincentivize schools to lower costs, reduce individual accountability, and, in the case of forgiving government-held debt, throw public budgets into disarray.

Proponents say the student debt crisis has gotten out of hand and eliminating or reducing student debt would put more money into the hands of consumers, boosting the economy and making education more attainable. They take issue with an economic-cultural structure requiring a college education for higher-paying, advanced jobs.

What is indisputable is American student borrowers are in more debt than they’ve ever been in history. In 2006, the earliest year in which the Federal Reserve reported the number, Americans held a collective $481 billion in student debt. As of the beginning of 2021, that figure sat at $1.7 trillion.

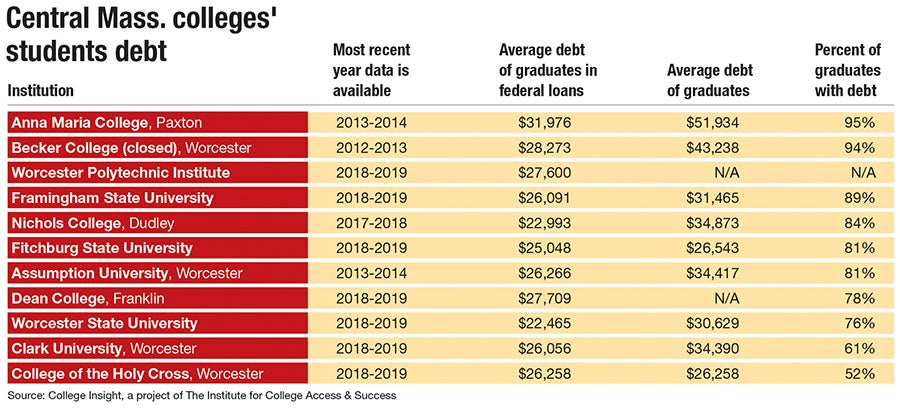

In Mass., the average student borrower is indebted $34,100, according to research group EducationData.org, as 12.4% of the state’s residents have student debt, with Mass. holding a collective $29.2 billion in student debt. These figures mirror national ones.

Shrinking these numbers is not as straightforward as popular talking points. While lower income students may have historically been advised to consider public schools in an attempt to reduce the costs of their education, in Mass., such a distinction may now be futile. According to a 2018 report from the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center, the amount of debt students incur at public colleges and universities is almost equal to the amount of debt incurred by graduates of private schools.

The report found while in 2004 both public and private college graduates in Mass. held student debt in comparative numbers, by 2016, the amount of private school graduates who held debt had decreased from 60% to 54%. The amount of public school graduates who held debt increased from 58% to 73%.

The Budget and Policy Center report partially attributed the rise to a 32% cut in state funding for higher education in the last 20 years. Although state support decreased about $3,000 per student by 2018, tuition and fees rose $4,600.

Federal solutions

Federal student loan repayments and interest accrual are on pause because of the coronavirus pandemic, a relief set to expire on Sept. 30. Although President Joe Biden said on the campaign trail he supported forgiving $10,000 in student debt per person, he has not yet followed through with that goal, although he tasked the Department of Education in April to explore his legal authority to erase debt through executive action.

This lack of action stands in stark contrast to a push by some Congressional Democrats, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), campaigning for Biden to forgive $50,000 of student debt per borrower, an effort working itself toward a fever pitch as the clock ticks toward October.

Some 92.6% of student debt is held by the federal government, according to EducationData.org.

Moreover, student loan debt challenges are greater for students of color, a trend with significant implications for the racial wealth gap. A 2019 report from the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University in Waltham found 49% of Black borrowers and one-third of Latinx borrowers defaulted on their student loans, compared to 20% of white borrowers. The same report found 20 years after starting college, student debt held by white borrowers was reduced by 94%. In contrast, Black borrowers still owed 95% of their debt.

Massachusetts solutions

Efforts are underway from Central Massachusetts legislators on both sides of the political aisle to lessen the burden for borrowers.

Last year, Gov. Charlie Baker signed into law the Student Loan Borrower Bill of Rights, a piece of legislation sponsored in part by State Rep. Natalie Higgins (D-Leominster). The law, Higgins said, took a two-fold approach to helping and protecting borrowers navigate their student debt.

The first part of the law aims to hold student loan servicers accountable by requiring they be licensed and adhere to a code of conduct. The law allows for the state to take action against student loan servicers breaking rules or harming borrowers. While the law doesn’t make student loans go away, Higgins, an advocate for total student loan forgiveness, said it provides oversight and repercussions for the worst actors.

The second piece of the legislation went into effect on July 1, establishing a student loan ombudsman, under the Mass. Attorney General’s Office. The person filling the role is Arwen Thoman, deputy director of Attorney General Maura Healey’s insurance and financial services division.

As ombudsman, Thoman will be tasked with resolving student complaints, educating borrowers, monitoring student loan servicers, and submitting annual reports on borrower complaints and trends. In a July announcement naming Thoman, Healey’s office said Thoman will complement the Student Loan Assistance Unit, established in 2015.

“My office is on the frontlines of this $1.7-trillion crisis, fighting on behalf of student borrowers in Massachusetts, and taking on a student loan system that is fundamentally broken and devastating to countless Americans,” Healey said in a statement announcing Thoman’s appointment. “The establishment of this ombudsman position will be critical in our ongoing work to help students and families invest in their future and get the relief they deserve.”

Still, Higgins said, much work needs to be done, particularly as the economy continues to recover from the coronavirus pandemic.

“People’s individual lives have not gotten back to where they were prior to Covid,” she said.

Higgins is supporting a bill, the Senate version of which is sponsored by Sen. Ryan Fattman (R-Uxbridge), to prohibit denying professional and occupational certificates and licenses because a person has defaulted on their student loans. Higgins said such a bill is common sense, and she’s hopeful it will pass.

“We shouldn’t be punishing employees,” Higgins said. “It would be a game changer.”

Separately, Higgins is sponsoring a bill to aim to make public higher education free by taxing higher education endowments exceeding $1 billion.

She doesn’t buy the argument making public college free or forgiving student loans would be bad for the economy, arguing putting money back into consumers’ pockets will allow them to make basic purchases, like buying a car.

Pedraja, head of QCC, concurred.

“We see education as a luxury or as a commodity or a privilege,” Pedraja said. “The way I see it, education is a basic human right, and it is necessary for the economy to advance and for us to have a trained workforce.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Monica Benevides, the author of this article, holds federal student loan debt eligible for federal forgiveness under the proposed plan.