Natick firm building a Devens facility to clean up use of the most abundant element in the universe: hydrogen

Photo | Courtesy of Electric Hydrogen

The founders of Electric Hydrogen (from left) David Eaglesham, Raffi Garabedian, Dorian West, and Derek Warnick

Photo | Courtesy of Electric Hydrogen

The founders of Electric Hydrogen (from left) David Eaglesham, Raffi Garabedian, Dorian West, and Derek Warnick

David Eaglesham wanted to find the next answer. As an entrepreneur-in-residence at the Bill Gates-funded Breakthrough Energy Ventures in Washington, he was also looking for a problem to solve.

Previously, Eaglesham was the chief technology officer at First Solar – an Arizona solar panel manufacturer and provider of utility-scale solar farms, and the supporting services, including financing, construction, maintenance, and panel recycling – until he retired after six years at the company in 2012. After leaving First Solar, Eaglesham needed to find what to do next and to find his focus. With that, he came to the conclusion that hydrogen, the most prevalent molecule in the universe, was the next logical step in the fight against climate change.

“Clean electricity alone doesn't solve the problem. It actually only solves about a third of the problem,” Eaglesham said. “If you look at it, there's only about a third of climate change that's attributable to renewable electricity production. So if all you do is clean electricity, then you only solve one third of the climate problem. The other two thirds are these super hard problems – like big industry; it’s shipping; it's airplanes; flight; and it’s just a mess of problems that are super, super hard to solve – and hydrogen is a pathway to solve all of those.”

Hydrogen is an integral part of the economy, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. It is used in the production of ammonia, which is vital to manufacturing fertilizer. Hydrogen is used for refining petroleum, metal alloying and iron flashmaking, atomic hydrogen welding, in glass production, in the creation of semiconductors, LEDs, displays, photovoltaic segments, and other electronics as well as in hydrogen peroxide. NASA makes liquid hydrogen fuel, which is rocket fuel.

While this single element is vital to our lives and prevalent in the air and space, hydrogen is not easy to harness in the same way that water is. The main way – a thermochemical process – uses a large amount of energy from fossil fuels. Research is looking at developing alternative methods like water splitting or electrolytic, but even those use fossil fuels.

That’s where Eaglesham saw an opportunity: an electrolyzer running off of renewable energy.

“There's an existing industry that's about $120 billion a year that involves making hydrogen and using it to make fertilizer and chemicals and plastics and all that other stuff,” Eaglesham said. “That industry contributes sort of a couple of percent of the total emissions, which is 2%. Doesn't sound like a lot, but actually it's a huge amount, sort of comparable to Exxon for perspective.”

Eaglesham assembled a team to find a way to make electrolyzers cleaner for the environment and efficient for manufacturers to use. He teamed up with Derek Warnick, who was also at Breakthrough Energy, to be the CFO; Dorian West, who worked at Tesla for 15 years, to be to the executive vice president of engineering; and Raffi Garabedian, who worked at chief technology officer of First Solar for eight years, as CEO. The company they founded is Electric Hydrogen. The team founded the company in December 2019, and it was self-funded until March 2021 when Electric Hydrogen raised money for the first time: $24 million, with Breakthrough Capital leading all investors. The team opened an office in Natick and another in San Carlos, California, which is situated between San Francisco and San Jose.

Next up, Electric Hydrogen is opening a manufacturing facility in Devens to begin building its advanced electrolyzers, which can run off of renewable energy thanks to technological advances the company has made.

Making clean energy cheaper

What Electric Hydrogen is trying to do is similar to what First Solar did: make it cheaper, which will encourage the industry to change. When Eaglesham was at First Solar, the company started a price war to drive the cost down so it was competing with the cost of coal, which was inexpensive in comparison.

“The goal is to make renewable hydrogen as cheap as fossil hydrogen,” Eaglesham said.

The issue with running an electrolyzer on renewable energy like solar or wind is that power isn’t always on, and a machine like an electrolyzer previously needed to stay on to operate.

“Renewables are actually only on less than half the time.,” Eaglesham said. “So then the electrolyzer has to be cheap enough that the economics work even when it's turned off half the time.”

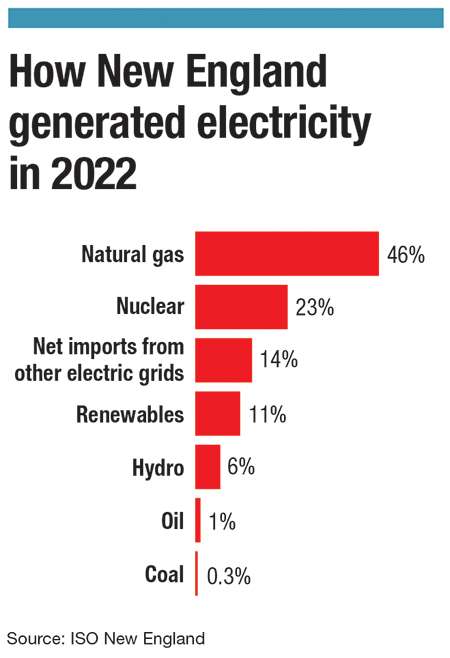

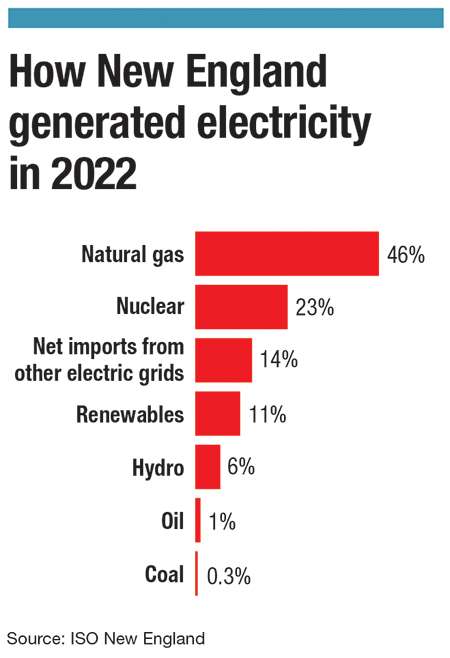

Renewable energy is a linchpin of Massachusetts climate plan. The state is actively working to bring more renewable energy online as it tries to meet its goals of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and an 85% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels. The state is trying to bring on more renewable energy via offshore wind farms, solar, hydro energy from Quebec, and onshore wind farms in Maine. Creating a more sustainable electric grid is still a ways off as grid operator ISO New England reported in 2022 that 46% of the electricity generated for the region came from natural gas.

Yet, the changes coming to the Mass. portion of the grid are mandatory.

“These are legally binding and they're going to require significant electrification of the transportation and building sectors,” Michael Judge, undersecretary of energy for Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, said at the Mass Energy Summit in May, hosted by WBJ.

One area that can reduce greenhouse gasses is hydrogen production. By tying electrolyzers to renewable sources like solar panels, Electric Hydrogen is pushing technology forward. Now it needs to begin building its product. That’s where Devens comes in.

The advantages of Devens

Devens has the power supply Electric Hydrogen needs to test its machines and is close enough to the research and development at the company’s Natick to make construction easy. Plus, it’s near Boston, where the company feels it can find the talent it needs on the engineering side.

Electric Hydrogen’s planned Devens building is “very much configured in a way that was advantageous for us to start our operations rather quickly,” said Santiago Rojas-Carbonell, the project manager for the Devens factory. The factory in Devens gives the company a chance to fill its first orders for electrolyzer. The facility will be operational by the end of the year.

“We're definitely taking a very aggressive approach to ramp up our factory.” Rojas-Carbonell said. “Our factory in Devens will have a capacity to produce 1.2 gigawatts worth of electrolyzers per year.”

Electric Hydrogen is trying to win a race to make hydrogen more efficient, cheaper, and cleaner. The U.S. Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy and the U.S. Department of Energy has $750 million in funding available for clean hydrogen technologies. There’s money to be made in the sector.

And there’s the idea by enhancing hydrogen, some good can be made on the environmental side. Maybe we can turn the clocks back and alter some of the impacts of climate change begun with the Industrial Revolution, started in 1760 and increased the reliance on fossil fuels in the 20th and 21st centuries.

“The Industrial Revolution was done wrong,” Eaglesham said. “We started the Industrial Revolution with water wheels and things like that, and then we got seduced by oil and coal and fossil fuels. We took this kind of wrong turn. It seemed like a good idea at the time, but in hindsight it turned out to be a problem. And now we're redoing the whole Industrial Revolution, and I think it's kind of cool that we're doing it in Northern Massachusetts, which is kind of the home of the Industrial Revolution in the USA.”

In addition to Electric Hydrogen’s 187,000-square-foot facility in Devens, Commonwealth Fusion Systems is next door trying to harness fusion power for the next evolution in renewable energy, making Devens something of a clean energy epicenter.

“This is a way,” Eaglesham said, “for the region to be on the ground floor of the next Industrial Revolution.”

0 Comments