The workplace has long been many different things for many different people – a space to chase one’s career ambitions, to network, pursue passions, make ends meet, among others – but for some, it’s been a safety net.

An incidental characteristic of workplaces, however they look, whether a traditional office or restaurant, retail space or something in between, is they operate as tacit safety checks, a planned slice of the day where individuals leave their homes and enter, in some way or another, a more controlled environment. For survivors of domestic violence, this time and distance from their living space can be a lifeline; with the coronavirus pandemic shutting many of these workplaces down, and rampant unemployment and furloughs, that lifeline has been severed.

“When we were employers in person, it was a lot easier to know what was happening with our employees,” said Debra Robbin, executive director at Jane Doe Inc., a statewide coalition of organizations which work to combat sexual and domestic violence, based in Boston.

“It’s really hard to be a responsible employer,” Robbin said, “when you can’t walk around and check on people and see how they’re doing.”

Although there are still many taboos around discussing domestic violence at work, for fear of overstepping interpersonal boundaries, waking up and physically going to a workplace several days a week makes sure, at the most basic level, that a survivor is seen by other people on a regular basis, and provides a buffer against one of the most common elements of abuse: isolation. Oftentimes, the workplace provides an opportunity for survivors to connect with help, whether by calling a hotline, legal authorities, or even friends.

“A lot of your protocols and the ways of your organizational culture might have changed, but the victims keep on coming, so how are workplaces going to adapt to this new reality?” Robbin asked.

A common problem, complicated

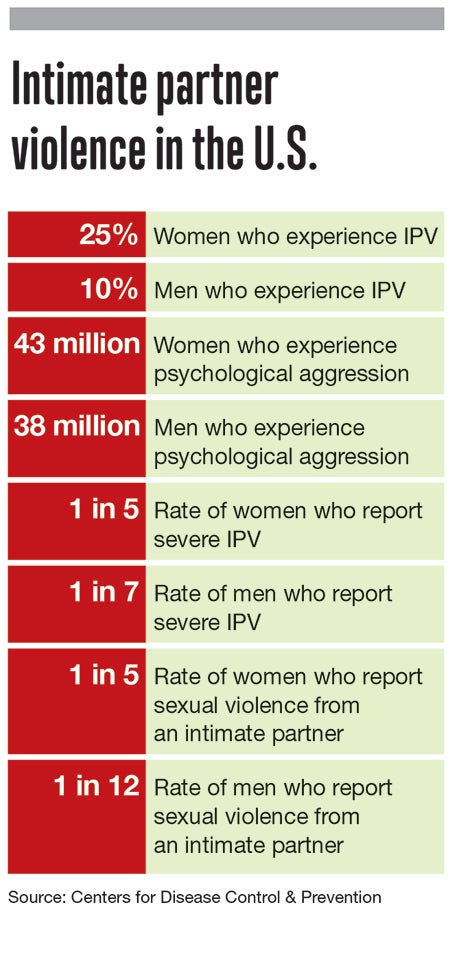

According to data published by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, a quarter of women experience some form of intimate partner violence in their lifetime, as well as nearly one in 10 men. Under the CDC definition, intimate partner violence includes physical violence, sexual violence, stalking and/or psychological aggression.

Although domestic violence may only be one aspect of a person’s life, it can carry devastating consequences. Over one-third of female survivors and 11% of male survivors experience physical injury, and it can also lead to longer-term health problems, like heart, nervous system, reproduction, muscle and bones conditions, which the CDC reports are often chronic.

Mental health issues are a concern, particularly with regard to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Moreover, the risk of dying from domestic violence cannot be understated: When authorities are able to determine the relationship between victims of homicide, more than half of female victims are killed by an intimate partner, according to the CDC. In turn, nearly one in five homicides victims in general are killed by intimate partners.

All of this data, which is well-circulated by domestic violence organizations operating at the state and federal level, formed the backdrop for a sudden decrease in domestic violence hotline calls reported at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, when stay-at-home orders sent many people home, either temporarily or indefinitely.

Some domestic violence organizations reported as much as a 50% decline in requests for services at the start of the pandemic, according to an April report by New York City publication The Guardian.

An escalating issue

Deborah Hall, director of domestic violence services at YWCA Central Massachusetts, said the decline was, indeed, noticeable in the Worcester area, when the initial economic lockdown began.

“That made sense, at the time, because a lot of our participants and people who may have called us were sheltering in place with their abuser,” Hall said.

But, that dip was not sustained. Come June, when many businesses began to reopen, and when social distancing restrictions were loosened, calls for help increased, once again. And by the end of summer, she said, not only had calls increased, but the organization was fielding reports of increased and escalating violence.

Around the same time, two murder-suicides were reported in the area – one in Worcester, and one in Gardner.

“That put us all on alert in the DV world,” Hall said.

The agency, which switched to tele-advocacy at the start of the pandemic, which is to say providing services remotely, began to emphasize safety planning and helping to facilitate restraining orders.

“People look at their situation again, and that they don’t want that to be them,” Hall said of the murder-suicides’ impact. “And so sometimes, you will see an increase in calls after you’ve had a DV-related homicide.”

Moving forward

Advocates interviewed for this story expressed concern about the upcoming holidays, and the ways which already stressful seasons, made more stressful by the coronavirus pandemic, may impact survivors who are in unsafe situations.

“Normally survivors try to keep it together around the holidays, for the sake of the family,” Hall said. “But now that you should not be having big gatherings, I don’t know.”

Hopefully, she said, with positive vaccine developments, the community is at a pandemic turning point, although the problem is far from gone.

In the meantime, there are considerations which business owners and employers could consider to help make their workplace a safe space for providers, Hall said. Even something as simple as poster condemning abuse, featuring a hotline number, could send the right message, so folks in those situations feel safe.

“Even businesses who even bothered to put up posters, maybe saying abuse is not okay, like just visuals,” she said. “That folks that may be in those situations with space, or there’s just the number they may not want to talk to you but they may take that number down when they’re in the bathroom or something.”

The idea, she said, is to make domestic violence less taboo to talk about.

“If people think it’s safe to open up,” Hall said, “they probably would.”