As the economic climate has shifted over the decades, some Central Massachusetts companies have left the region.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

It’s been 47 years, but Steve Rowse still remembers his first shift at the family business.

In the spring of 1977, Rowse clocked in for the first time at Veryfine Products, the Littleton-based juice manufacturer purchased nearly eight decades earlier by his great-grandfather Arthur. Mixing fruit punch was the 16-year-old’s task. He poured water into a 1,000-gallon tank and combined it with things like sugar and apple concentrate to make the company’s signature sweet drink.

Some children of business owners end up working at their parents’ companies because they’re told to – because mom or dad needs an extra set of hands or a succession plan. But for Rowse, there was no pressure. He never wanted to do anything else.

“In second or third grade I did a drawing of what I wanted to be when I grew up. I wanted to be a forklift driver, a goal I have achieved,” he said. “It’s probably important to say, my father and grandfather were around when I was a kid. Neither one set any expectations, like ‘you’re the oldest grandson, you have to be prepared.’ It was my decision to join the family business.”

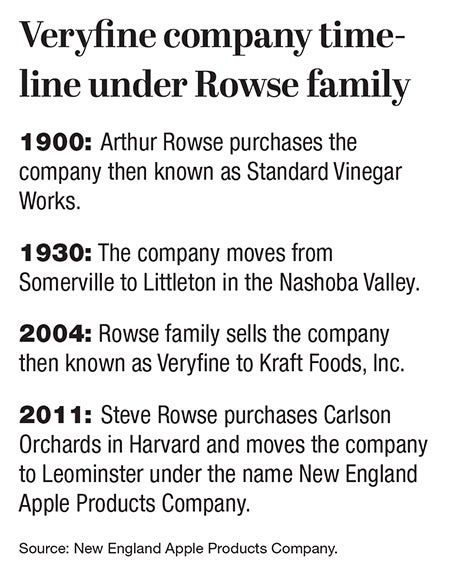

Founded in 1865 in Somerville, Veryfine was a New England company, through and through. Originally called Standard Vinegar Works, it came under the ownership of the Rowse family in 1900 and moved to Littleton 30 years later to be closer to the apple-rich Nashoba Valley.

As the economic climate of the region and the nation as a whole shifted over the decades, it became one of the many Central Massachusetts companies to leave the region, blown away by consumer demand shifts.

Veryfine was sold to Kraft Foods in 2004, and its Littleton plant closed in 2015 under the ownership of Sunny Delight Beverages. Veryfine still exists today under Connecticut-based Harvest Hill Beverage Company, which is owned by private equity firm Brynwood Partners.

Rowse left Veryfine weeks after the Kraft sale. In 2011, he started New England Apple Products Company in Leominster after purchasing Harvard-based Carlson Orchards. He wasn’t involved with the business when the Littleton plant closed, but he was sad, although not terribly surprised.

“I figured it was going to be a struggle without a new product idea that never seemed to happen,” he said.

Times they are a’changing

Technology, consumer demands and cultural trends all influence which companies end up being winners and losers over time. Indoor shopping malls, for example, slowly fell out of favor starting in the 1990s thanks to the internet.

In Veryfine’s case, Rowse said, it was simple. Large beverage companies wanted to get into the juice and flavored water businesses. Veryfine’s Fruit2O flavored water sold well, Rowse said, but the family-owned company wasn’t big enough to justify competing with the Coca-Colas of the world.

“The large carbonated beverage companies figured out people wanted stuff that’s not always brown and bubbly and got serious about distributing juices,” he said. “We figured we better get out of the way before we get trucked over by the big beverage guys.”

In the case of Fidelity Bank, the Leominster-based financial services company, the decision to merge holding companies with another bank came down to doing more for customers.

This year, the bank’s parent company formally merged with Mutual Bancorp, the parent company of Hyannis-based Cape Cod 5. The idea, said Fidelity chairman and CEO Edward Manzi, was to create a single holding company for two different banks with strategically aligned missions and values. The merger created a holding company with a combined $7 billion in assets. Fidelity previously had $1.5 billion in assets on its own.

“If we could find a like-minded partner, to share and combine a holding company to share costs, and things like technology, human resources, finance and accounting, and risk management, then we could make bigger investments and stay hyper-local focused in our respective markets while being able to invest even more than either of us could alone,” said Manzi, who is also now vice chairman, chief strategy officer at Mutual Bancorp.

“We thought it could get us further faster, and that's what we set out to do.”

Although the merger is still in its infancy, Manzi said Fidelity quickly took advantage of new customer services available through Cape Cod 5. The Hyannis-based bank has a robust wealth management and trust department Manzi said Fidelity offered to some of its clients, and the Leominster bank will also receive $5 million for a charitable endowment, which it will invest in a mix of bonds and stocks and donate to the community.

“It will be in addition to our normal philanthropic giving. We’ve been averaging $400,000 plus a year,” he said.

The holding company merger also makes sense from a big-picture banking standpoint, Manzi said. When he started at Fidelity in the late 1990s, there were more than 12,000 banks in the United States, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Now, that number is about 4,000. Combining with Cape Cod 5 allows Fidelity to remain competitive while keeping its focus on the community, which is its bread and butter, Manzi said.

A sight for sore eyes

It’s impossible to miss the giant eyeglass statue in front of the brick clock tower just beyond downtown Southbridge. The small industrial city was the original home of American Optical Company, a pioneering glasses manufacturer founded in the mid-19th century.

By the 1890s, American Optical was the largest optical company in the world. Workers crafted goggles for military pilots, according to the company’s website, and invented the aviator, a practical style of eyewear that evolved into a persistent fashion trend. The company was also the favored eyewear brand of President John F. Kennedy, who visited the sprawling Southbridge facility in 1958.

American Optical closed its Southbridge glass manufacturing plant in 1979, and the last lens produced in town was made in 2005, according to the Optical Heritage Museum. Its corporate headquarters moved to San Diego, California, in 1997.

The company, plus still-operating manufacturers like Dexter Russell and Hyde Tools, created quite the vibrant community in Southbridge back in the day, said Margaret Morrissey, library director of the town’s Jacob Edwards Library.

“On Thursday evenings, people would walk out and about downtown. And now, sadly we don't have very many people in town, and it’s a different world now,” Morrissey said.

Morrissey arrived in Southbridge from her native Ireland in the late 1980s, she said. Back then, the community was still reeling from the shock of losing one of its biggest points of pride. Stories of “the AO,” as people call the optical company, are still prevalent in Southbridge to this day, Morrissey said.

“Everybody has a connection to the AO. That’s why it’s still a vibrant topic of conversation in the community, even though generations have now grown up without seeing AO in operation,” she said. “There was a Christmas party for children that was apparently spectacular. Those children are now people I talked to, and they’re still starry-eyed about how wonderful it was.”

Moving into the future

The former AO headquarters is getting a 21st-century makeover. Spearheaded by local developer Charles “Chip” Norton Jr., the historic structure will eventually be a mixture of affordable residential, manufacturing and office space. Its 1.2 million square feet are about half developed so far, Norton said. The future production facility is just under 200,00 square feet, and the residential component will have 266 units. The property was recently listed on the National Register of Historic Places, he said.

“What that allows you to do is access federal and state tax credits to offset development, and that’s very important for the residential project,” said Norton, president and owner of Franklin Realty Advisors in Wellesley Hills.

Rowse is no longer affiliated with Veryfine, but the family juice legacy carries on. He purchased Carlson Orchards from the Carlsons, his lifelong family friends, to bring their apple orchard to the next level of production. The company sells more than a million and a half gallons of cider per year across New England and eastern New York.

It’s great, Rowse said, because he’s spent most of his career doing the only thing he ever wanted to do.

“I tell people, ‘I don’t know how to do anything else,’” Rowse said. “It was a good fit for me, it was a good business play, and consumers were looking for minimally processed, natural local products. It clearly fit the bill and it was a win-win for everybody, including for customers.”