when entrepreneurs of color turn to banks and other investors, research shows they’re often given less consideration than white founders.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

As a social worker helping children, families, and adults with substance-use disorders in North Central Massachusetts, Kimatra Maxwell noticed a gap in the services people often received. There weren’t enough skilled and trained people whose backgrounds matched those of the people they served, especially people of color.

“I worked on teams that are predominantly white, sometimes being the only person of color that a family could relate to,” she said.

Maxwell had an idea for a business: a coaching and counseling service to intentionally focus on the needs of a diverse range of clients.

“So in 2018, I called my partner and I’m like ‘I’m quitting my job,’” she said.

Maxwell said she was lucky in some ways. Her partner was supportive. Her mother invested the first $1,000 to get her new company, Connecting to Greatness, incorporated and insured.

But the early years were tough. She and her partner found themselves cutting back on essentials. They racked up credit card debt. Some months, they couldn’t pay the rent on time, though, fortunately, their long-time landlord was understanding.

By 2020, Maxwell said, she was making three times what she’d earned as a salaried social worker.

But, when she approached a bank for a loan to help invest in growing the business, she was told the business’s revenues weren’t high enough to make that happen.

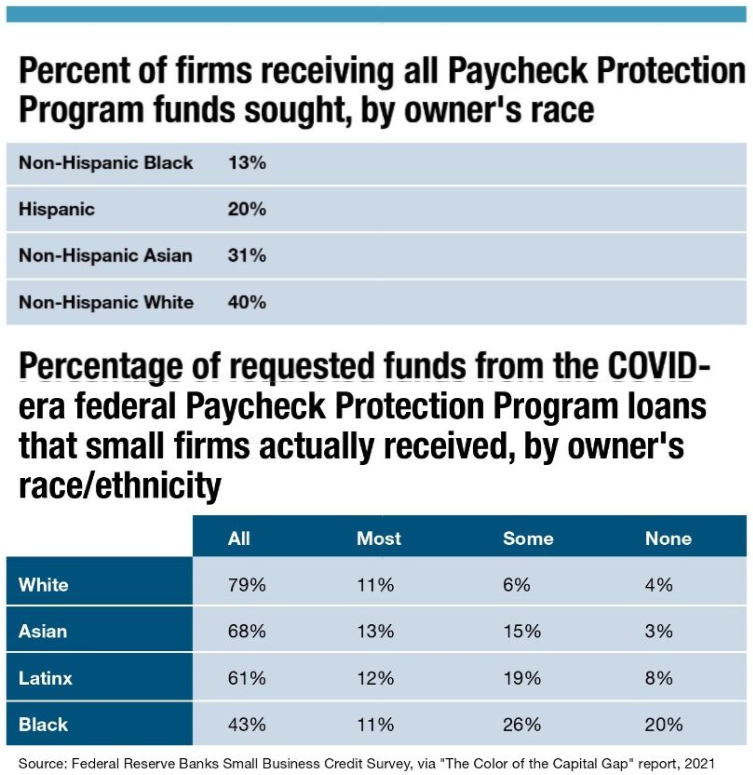

Maxwell is far from alone. According to the 2021 report “The Color of the Capital Gap” by Boston Indicators and the Boston Foundation, most entrepreneurs use personal or family savings to start a business. Yet, because of a history of racism and unequal treatment, white families have five to eight times the wealth of Black and Latino families on average. And, when entrepreneurs of color turn to banks and other investors, research shows they’re often given less consideration than white founders in similar circumstances.

This helps explain why, although Massachusett is about 68% white, white people make up 82% of the state’s entrepreneurs.

Connecting entrepreneurs with financing

To help close this gap, a number of programs and institutions help provide financial support for underserved communities.

The North Central Massachusetts Development Corp., the economic development arm of the North Central Massachusetts Chamber of Commerce, works with the U.S. Small Business Administration as a community advantage lender, which helps it support early stage companies that may struggle to qualify for bank loans or win investors.

“A lot of banks, they’re very, very regulated, so it’s difficult for them to take risks,” chamber President and CEO Roy Nascimento said. “But we don’t mind taking on a little bit more risk because that’s part of our mission. Typically, because they lack capital, they lack credit history, and, because it’s a startup business, it’s considered risky.”

To reach underserved entrepreneurs, the NCMDC works with chambers of commerce both in North Central Massachusetts and beyond and has links to local organizations like the Spanish-American Center in Leominster. It receives referrals from banks and credit unions to help with loans that the traditional financial institutions can’t make.

And it has staff who speak Spanish, Portuguese, and Hmong, who can help immigrant entrepreneurs.

In 2021, the NCMDC made 84 microloans through the program, totaling $1.75 million, said Nascimento, with 60% of the entrepreneurs who received the loans being considered as from underserved groups, meaning people of color, women, immigrants, or people of low to moderate incomes.

Among them was Connecting to Greatness. After the bank told her in 2020 she couldn’t get a loan from them, Maxwell approached the chamber and received a $20,000 loan from NCMDC to open a new, larger office. After the pandemic struck, she was able to get support from business-assistance programs, helping the company to stay afloat amidst the uncertainty of the time and even expand.

This year she received another $25,000 loan from NCMDC, this time for purchasing new equipment for virtual counseling and for hiring two more full-time clinicians.

Helping businesses get loans

Entrepreneurs of color in other parts of Central Massachusetts face similar barriers. Katia Norford, secretary of the board of directors at Main South Business Association in Worcester, said the majority of businesses in the neighborhood are small mom-and-pop operations owned by Black and Latino people. Many are too busy doing the work of the business to take care of all the paperwork and research needed to get financing.

Norford herself is co-owner of Carlito’s Barbershop, together with her husband, Carlos. She said she’s fortunate that, when the couple was just starting the business, she was able to go back to college to get an associates degree in accounting. But, even so, the fact the business has historically operated mostly on a cash basis meant it was hard to provide all the documentation lenders need to make loans.

Fortunately, MSBA is able to offer microloans, funded through a federal grant. Norford’s business, along with six others in the neighborhood, received loans of up to $5,000 this year. For Carlito’s, that meant money for a new air conditioner and two new chairs, as well as some help with rent, all at an excellent 2% interest rate.

In her work with MSBA, Norford helps fellow business owners in her neighborhood learn best practices for things like accounting and taxes, which helps them qualify for loans and other financing. But she said she’d also like to see lenders show more understanding about the unique needs of small local businesses.

“I really would like to see more help for the small businesses, when it comes especially to loans, to have a little more flexibility,” she said. “Most of them have been there for years, and nobody is taking that into consideration.”