Community Harvest Project’s food donations have become more critical than ever during the COVID-19 pandemic, and they remain so now as pandemic emergency declaration-related federal and state emergency allotments end and the costs of food continue to rise.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The model at Community Harvest Project, a nonprofit farm and orchard in Grafton and Harvard, is unique in the way it makes food available for donation. On a given week in the summer, more than 300 volunteers help harvest the 320,000 pounds of produce the farm produces each year. Its 6,000 annual volunteers come to the farm year round, in smaller numbers during the winter, supplementing CHP’s six full-time and six part-time employees who manage 15 acres of farmland in Grafton and 30 orchard acres in Harvard.

Community Harvest Project does not distribute food directly, but rather partners with 23 other organizations in what Executive Director Tori Buerschaper describes as a business-to-business model.

Calling itself volunteer farming for hunger relief, Community Harvest Project’s food donations have become more critical than ever during the COVID-19 pandemic, and they remain so now as pandemic emergency declaration-related federal and state emergency allotments end and the costs of food continue to rise.

“We are hearing from our partners that our produce is so critical right now because of increasing costs across the board,” said Buerschaper.

Inflation, increased costs of other essentials, and ending federal programs have made the end of the pandemic anything but the end of a heightened food insecurity problem, said Jean McMurray, CEO of the Worcester County Food Bank.

“All these things created yet another crisis in addition to the pandemic,” said McMurray.

The growing hunger problem

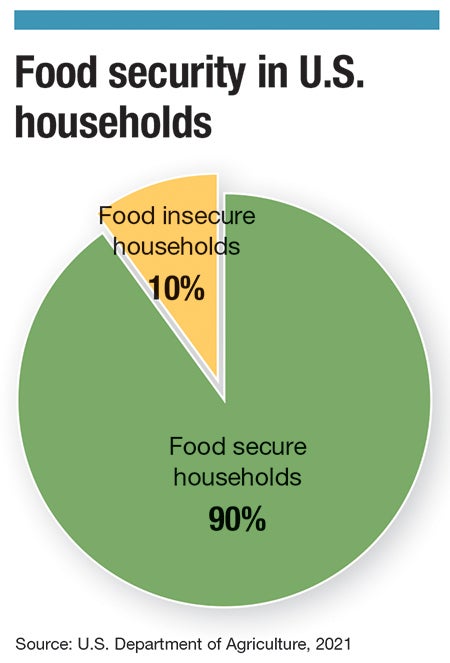

Food insecurity is defined as a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food, according to the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Government programs like universal free school meals, additional Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, and child tax credits made some individuals more food secure in the pandemic than they were before or are now, said Erin McAleer, president and CEO of Project Bread, a Boston-based nonprofit that does advocacy work in addition to connecting individuals with resources.

“Issues were exacerbated during the pandemic, but existing issues were also exposed,” said McAleer.

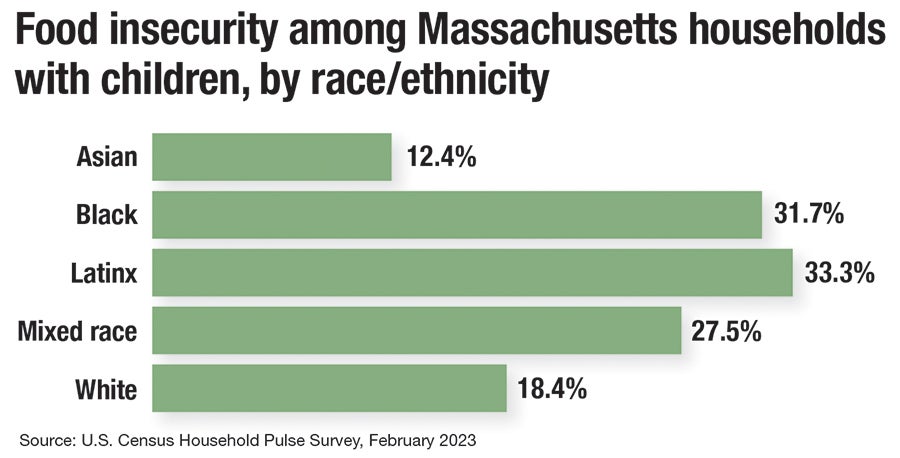

As of March, 22.2% of households with children in Massachusetts were food insecure, according to Project Bread. This is up from a pre-pandemic rate of less than 9%, and a mid-pandemic low of 12.5% in April 2021.

“These different programs started to be peeled back,” said McAleer. “Food insecurity has been slowly rising since then.”

In the Greater Worcester area specifically, McMurray has seen this play out as more individuals and families are coming to access food offered at the food bank.

“The situation with food insecurity in our communities is worse than it was during the pandemic”, said McMurray.

During the first year of the pandemic, the number of households being helped by the food bank had increased 15% by February 2021 from February 2020, said McMurray. By February 2022, that increase had gone down by 7%, said McMurray, citing unemployment compensation and SNAP benefits as aiding individuals and families in having the resources to purchase ample food.

As pandemic evolved and benefits began to sunset, however, the number of people going to the food bank is back up. February 2023 numbers were 30% higher than February 2022, said McMurray.

“What the pandemic taught us was that the government is the only entity that can scale up quickly to respond to a crisis of that level. Government programs were working and having the biggest impact,” she said.

Gov. Maura Healey’s administration has extended through June the additional SNAP benefits past the federal endpoint in March, which is allowing for extra benefits at 40% of what the federal government provided throughout the pandemic.

But a cliff is coming, if it is not yet here, and it is falling on nonprofit organizations to fill those gaps.

Grant funding is harder to get

Community Harvest Project helps its partners by providing free, nutritious, local food otherwise potentially unavailable, but while government funding for individuals is changing, so is the way organizations are accessing grants.

“In some ways grant funding was easier during the pandemic,” said Buerschaper, citing reduced requirements for applications and an additional awareness of the needs of the community that were present over the past few years. “Now focuses are changing, and priorities from funders are changing.”

While the total amount of grant funding has remained the same, the work that goes into courting new opportunities is altered, she said.

Community Harvest Project relies on grants for 45% of its annual operating budget, said Buerschaper. While volunteer labor helps the farm do what it does, the farm also relies on essential equipment to work efficiently and move the hundreds of thousands of pounds of food from the farm to where people can access it. The nonprofit has an annual budget of $1.1 million, according to the most recent tax filings made available on the data service Guidestar.

The organization receives two kinds of grants: those allowing for the continuation of existing programs, and those allowing for risk taking, perhaps resulting in ways to better serve the community, said Buerschaper.

In 2022, the organization received grants of each of those kinds from the Greater Worcester Community Foundation and Worcester insurer Fallon Health, in turn.

The grants it receives usually range from between $1,000 to $50,000, said Buerschaper. The GWCF grant, announced in October 2022, was a $75,000 development grant used for large capital purchases, like replacement of a heavy-duty forklift and a brush mower, which allows for efficient planting.

Fallon Health’s grant, which was an unrestricted program grant for $15,000, is to support operations and goals, including increasing the variety of produce made available to partners and improving the distribution system.

Increasingly, Community Harvest Project is emphasizing education in its mission. With access to thousands of volunteers each year, often people who are highly entrenched in the community, the organization is advocating for policy solutions to address the root causes that make its work necessary.

“We provide fresh fruit and vegetables because we believe everyone deserves it, and because our partners tell us people still need it,” said Buerschaper. “But hunger is a symptom of much larger problems.”