For every $1 a man earns in Massachusetts, women earn 83 cents, according to data from the National Women’s Law Center. That disparity is even greater for women of color, with Black women in Massachusetts earning 57.7 cents compared to white men, and Latina women earning 50 cents.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

For every $1 a man earns in Massachusetts, women earn 83 cents, according to data from the National Women’s Law Center. That disparity is even greater for women of color, with Black women in Massachusetts earning 57.7 cents compared to white men, and Latina women earning 50 cents.

These figures aren’t new, although they remain a jarring indicator of significant inequality in the workplace, as well as a gap that has proven difficult to close in a societal culture where discussing earnings in public or among peers remains largely taboo. But the persistent wage gap has certain organizations promoting a still radical notion flying in the face of that norm: salary transparency.

“Salary is something that as a society, we have been told, ‘Don't talk about this. Keep it to yourself,’” said public and political strategist Megan Costello, who has partnered with the Massachusetts Women’s Forum on a project called Wage Equity Now, which is collecting and plans to publish raw pay gap data from Massachusetts companies. Raw wage gaps are the percent difference between the average salaries of various worker groups, like men and women.

The norms around keeping salaries private, Costello said, have created a culture which holds women back, broadly, but specifically women of color, as well as Black men.

“When we talk about structural racism and all of these things, that’s really been the institution that has created this climate of pay secrecy, which has allowed for these inequities to persist,” Costello said.

Both employers and employees alike might balk at the idea of publishing pay gaps or sharing salary information, but the practice is not without precedent. Costello points to the United Kingdom, where the government publishes pay gap data for companies with 250 or more employees. That information is available in an easily searchable online database.

Reporting Massachusetts salaries

Similar to the UK database, the Wage Equity Now project, which Costello hopes to see established as its own nonprofit in the future, is collecting data from participating companies of any size.

Although asking employers to come forward with what might be less than flattering data may seem like an uphill battle, organizations like the YWCA, The Commonwealth Institute, and the Boston Women’s Workforce Council have laid foundational work for a larger-scale transparency initiative, Costello said.

“What I'm saying to [employers] is, ‘This is a time where leadership is really needed,’” Costello said. “And one way you can show that you, as an employer, are deeply committed to solving the inequities that exist between men and women, that exists between people of color – specifically black and Latinx and white people – is you can be bold, and report this data.”

Public reporting does carry a public relations risk, which Costello acknowledged. Companies are making themselves vulnerable when they share their own shortcomings, opening themselves up to criticism. But, Costello said, the other side to that proverbial coin is the option to course-correct in public view.

Companies who participate in Wage Equity Now’s mission give themselves the chance to show they are actively working to repair inequities in their workplace.

“People appreciate honesty,” Costello said. “They appreciate transparency.”

To an extent, wage gaps and salaries by industry are already available. Public companies are required by the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission to disclose the earnings of their top executives, as well as give the median wage of all their employees and what the CEO-to-median-worker wage ratio is.

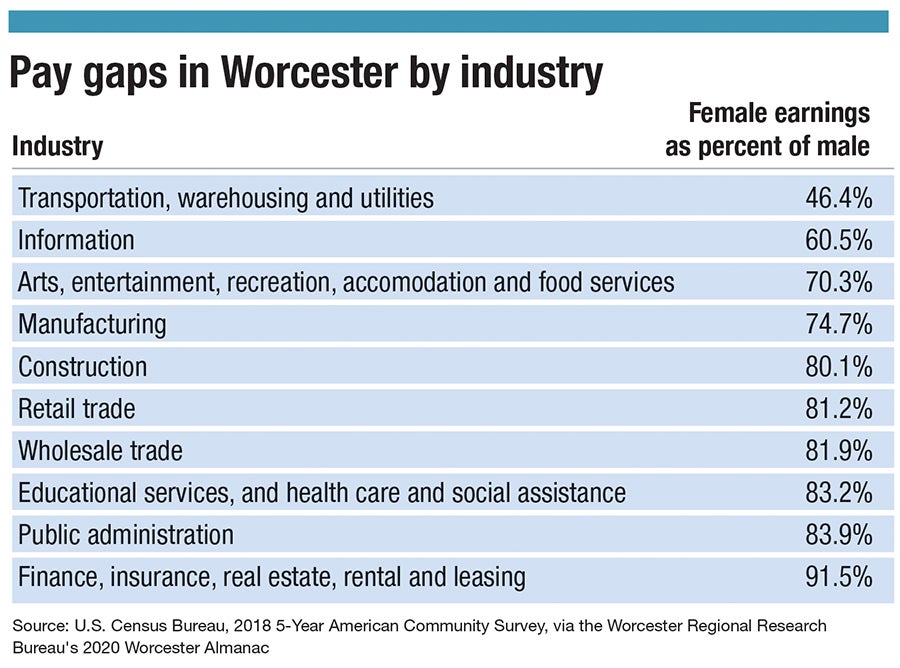

The 2020 Worcester Almanac, released in early September by the Worcester Regional Research Bureau, showed in the city of Worcester in 2018, men out-earned women in every field reported on, with the greatest gap found in the transportation, warehousing and utilities category, where a woman’s median salary is 46% of men in the same field. Women make up 21% of that workforce sector in Worcester.

In fields with roughly an equal mix of genders, men consistently outearned their female coworkers. In the arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation and food services sector, which is 47% men and 53% women, women earn 70% of what their male coworkers bring home.

The smallest gap reported in the WRRB’s almanac is in the finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing portion of the Worcester economy – another sector split relatively equally between male and female workers. In that sector, women earned 92% of what their male colleagues bring home.

“There’s some volatility because it includes both full-time and part-time workers, and some of the industry categories are pretty volatile with part-time,” said Paul Matthews, executive director and CEO of WRRB.

Increased legal protections

Interest in salary transparency exceeds experimental research and beta programs, at least in Massachusetts. On July 1, 2018, the Massachusetts Equal Pay Law went into effect, providing, among other things, protections for employees to share their pay with each other.

Under the law, potential employers may not ask prospective employees what they earned in their previous job, nor may they prohibit employees from discussing their wages or retaliate against them for doing so.

Yet, even two years after that law’s passage, women don’t completely understand what the law allows for and what it protects, said Denella Clark, the chair of the Massachusetts Commission on the Status of Women, who campaigned for the law’s passage and is the first woman of color to lead the organization.

“There needs to be much more education with employers and [human resource] professionals … [on] accountability, but then also on the employee,” Clark said.

In practice, salary transparency comes in many forms, such as simply posting a salary range with job listings, something none of Central Massachusetts’ 10 largest employers currently do, according to current job boards. This may leave prospective employees scrambling to crowdsource from websites like Glassdoor, which, although useful, may be unreliable.

“At bare minimum, if we can't publish existing salaries … we should publish salary ranges,” Clark said.

Employees in a company or industry may take matters into their own hands, as media workers did in 2019 with the Real Media Salaries document, a Google spreadsheet active to this day. The document was created when media workers across the country anonymously submitted their salaries, experience, and demographic information in order to generate a clearer picture of compensation norms.

An issue of racial justice

Since George Floyd’s killing by Minneapolis police in May, Clark said, more employers are understanding workplace equity as not just a gender issue, but a racial justice issue.

“This is now not just a moment,” Clark said. “It’s a movement.”

To that end, companies are establishing new positions aimed at protecting and promoting diversity and inclusion in their workplaces, she said, as for-profits and nonprofits are taking hard looks at who actually runs their companies.

“They're putting some real real meat behind it, and making sure that they are taking another look at not only their senior management, [but] the people in their organizations that are decision makers,” Clark said.

Still, it’s early to say how effectively these changes will be implemented, and Clark hopes these companies aren’t just checking a proverbial diversity box. It’s not just about hiring a more diverse staff, but about setting those new staff members up for long-term success, including fair compensation.

“If you value your employees and you want to retain your employees, you should be going out there doing market research relative to compensation and making sure that you're being equitable across the board,” Clark said.