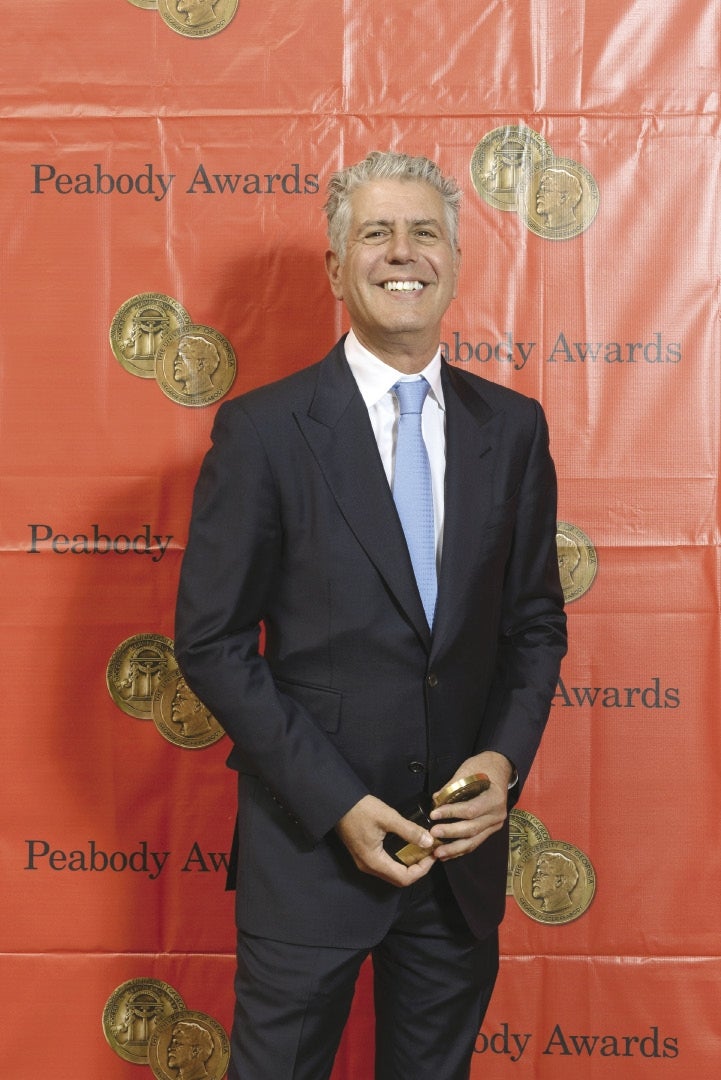

The bad news came all at once, especially for those working in mental health. In the span of a week in June, TV chef Anthony Bourdain and designer Kate Spade died of suicides, and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report brought to light a long and troubling trend: Suicide rates rose by 25 percent from 1999 to 2016, and the jump in Massachusetts was even worse.

The report wasn’t exactly big news for those who have been working to treat mental illness.

“That’s pretty consistent with what we’ve seen organizationally,” said Kate Adams, the director of mental health for the Harrington HealthCare System in Southbridge.

Yet, as mental health providers in Central Massachusetts have expanded services to deal with this growing need – psychiatry is now the largest department at Harrington Hospital in Southbridge – they bump up against a capacity strained by funding and staffing limits, leaving patients to have to wait for services.

“It’s really a travesty,” said Justin Looser, the executive director for behavioral health at MetroWest Medical Center and Saint Vincent Hospital. “If it were any other diagnosis, we wouldn’t stand for it.”

But mental health service providers are hoping the deaths of Bourdain and Spade have shown even successful, wealthy and famous people can struggle with mental health, and depression doesn’t spare any group of people.

“We haven’t done enough to reduce the stigma of seeking mental health services,” said Barry Feldman, a psychiatry professor at UMass Medical School.

The talk about the need to address the region, state and nation’s struggles with opioids have been widespread and led to new government task forces and seminars for health and business professionals, but discussion about mental health and suicide is more subdued, Feldman said, calling the CDC report “a clear indication of what we’re doing isn’t working.”

“When suicide comes up, people get really anxious about the topic,” Feldman said.

Troubling trends

Suicide rates in Massachusetts rose by 35 percent from 1999 to 2016, according to the CDC report. In a silver lining, Massachusetts had the third-lowest national rate in the past three years, with 10 suicides per 100,000 people.

With a Massachusetts population of nearly 7 million, that equates to roughly 680 people who have died of suicide in those years.

“It’s always shocking to see something like that on paper,” said Looser.

Calls to Samaritans, a nonprofit who helps those with mental illness and their loved ones, saw nearly a doubling in call volume in the weekend after the CDC report and Spade and Bourdain’s suicides, said Steve Mongeau, the Samaritans executive director.

Many of those were from people who said they were concerned about a loved one, he said.

Samaritans, which holds support groups in Framingham and Worcester, is known for its suicide help line, which it expanded in early 2016 to include text messaging.

More than 12,000 text conversations have been recorded since, Mongeau said, including a record high 600 in June.

“The silver lining was that the message was getting out that we need to help one another,” Mongeau said.

Nearly 45,000 Americans took their lives in 2016, with the suicide rate consistent among both all sexes and racial and ethnic groups, according to the CDC.

There is no consensus among doctors for what could be fueling the rise in suicides.

The report suggested warning signs may not have been present in many suicide cases.

Of those who have died of suicide, 54 percent were not known to have had a mental health condition.

“You’re always kind of scratching the surface,” said Adams from Harrington. “There’s always the need out there.”

New facilities, more providers needed

Central Massachusetts providers have been responding to a rising need, with more on the way.

In Worcester, UMass Memorial Health Care is building a 120-bed psychiatric hospital slated to open early next year. Saint Vincent Hospital opened an eight-patient wing of its emergency department committed exclusively for behavioral health on what was a loading dock and offices. The hospital is planning to expand its inpatient mental health wing from 13 beds to 20.

In Southbridge, Harrington HealthCare opened Harrington Child and Family Services Center in February, purposely avoiding a phrase like “mental health” in its name for the stigma against getting professional help. It added staff to a similar center in Dudley.

Harrington has more than doubled the size of its behavioral health staff in the past two years, Adams said, growing from just one outpatient behavioral health site to nine. Psychiatry now makes up the largest department at Harrington Hospital in Southbridge.

“It’s staggering,” Adams said. “No matter how much staff we add or programs we add, it’s not enough.”

MetroWest Medical Center has the same issue, with both inpatient and outpatient services constantly at capacity, Looser said.

MetroWest has added staff but is still constrained by the cost of adding or expanding units, or of finding enough specialists to staff them, Looser said. MetroWest Medical Center, which has 80 inpatient mental health beds, is considering an expansion based on the area’s needs. In the meantime, patients might have to wait weeks for placement.

Heywood Medical Group opened a day program for those battling both substance abuse and mental illness at the Quabbin Retreat in Petersham last June.

“This is something that we’ve seen coming down the road for a long time,” Nora Salovardos, Heywood’s director of behavioral health, said of rising mental health needs.

Heywood formed the Montachusett Suicide Prevention Task Force six years ago after seeing cases of suicide more and more often – including in schools. The task force has grown to include 22 area communities, with programs for men, youths, survivors of those who’ve died of suicide, and military families.

Barbara Nealon, who co-chairs the task force with Salovardos, said the task force has shown results at least locally, where suicides are down sharply in Gardner, where Heywood is based.

Other towns have wanted to add in more services, too, but the staff has bumped up against how much it can handle, Nealon said.

“There’s only so much we can physically do as a group,” she said.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said that MetroWest Medical Center was planning an expansion from 12 beds for mental health patients to 20. It has 80 such beds.